SCIENCE MEETS INDUSTRY

Exhibition Hall at the Crystal Palace in London

Unit

Overview

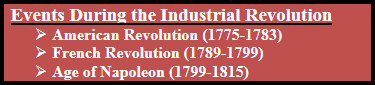

While

the effects of the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment opened a new

political era, people also were experiencing rapid changes in their economic and

social lives. The Industrial

Revolution, which began in Great Britain, spread to the European continent and

the rest of the world as the nineteenth century unfolded. Generally speaking, the Industrial Revolution

began in the late eighteenth century and continued throughout the nineteenth

century. It was a prime example of a

series of developments that took place while other events were unfolding on the

world stage. Let’s see how it all happened.

STOP: Answer Section A Questions

Not

the Same Old Family Farm

Before

industry took center stage, however, the continuation of the Scientific

Revolution transformed agriculture in Great Britain. With remarkable results, changes in farming

during the early 1700’s altered techniques and methods that had been practiced

since the Middle Ages. Through a policy known as enclosure, wealthy British landowners bought and fenced village

lands. In order to make this a

profitable venture, they began to look for ways to increase their

harvests. Fertile soil was a necessary

component for higher yields, and scientific farmers soon found new procedures

to assure its conservation.

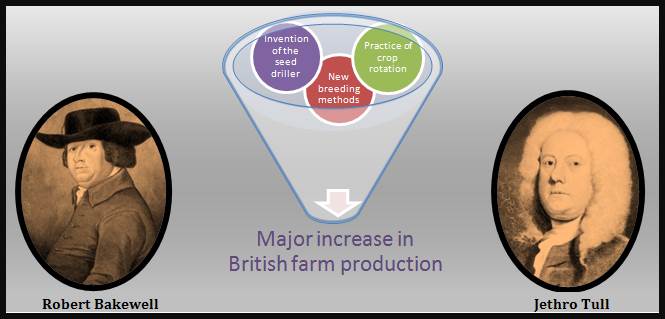

For

centuries, the chief method for this had been to let one-third of the property

lie fallow every three years. This meant one-third of Great Britain’s farm

land was out of production every year.

Viscount Charles Townsend remedied the situation by promoting crop rotation,

a system which alternated the plants which were grown annually. This renewed the soil without any loss of

production. The invention of the seed

drill by Jethro Tull in 1721

replaced sowing seeds by hand and allowed farm workers to plant in well-spaced

rows at exact depths. Scientific

research by Robert Bakewell resulted

in improved breeding methods, and livestock owners began raising larger animals

which also increased the food supply. By

1870, British farmers were producing 300% more food than they were in 1700, but

British industries made extraordinary advances as well.

STOP:

Answer Section B Questions

Why

Britain?

Even

though Great Britain was not the largest country in Europe in 1700, it did have

certain qualities that made it a prime candidate for industrial growth. The country possessed three natural resources

essential to the new machinery of the age:

water, iron and coal. Geography also favored the industrial

development in Great Britain. As an

island nation, it possessed many excellent harbors and a fleet of merchant

ships ready to access new markets. These

ships were owned by wealthy merchants with money to invest in new

projects. British businessmen not only

provided necessary financial backing but also had an interest in science and

new technology. Great Britain housed

Europe’s soundest banking system and provided loans to worthy inventors. Although the British participated in many

wars during the eighteenth century, none were fought on their own soil. Therefore, businesses in Great Britain did

not have to repair the damages caused by an enemy invasion.

Great

Britain’s increasing food supply also helped to promote industrial growth. As a result, health conditions improved, and

the annual death rates began to decline.

Since the birth rates remained steady throughout the 1700’s, the number

of people grew rapidly, and the populace doubled in just one hundred

years. This population explosion gave

industrialists a ready supply of labor for the new factories. The increase in agricultural production

caused prices for food to decline so British citizens had more money to spend

on consumer goods such as clothes and shoes.

Parliament, the British

law-making body, included a large number of merchants and businessmen who

supported laws favoring new investments and trade. All of these factors, combined with Great Britain’s

stable government, created favorable conditions for major industrial growth.

STOP: Answer Section C Questions

One

Thing Led to Another

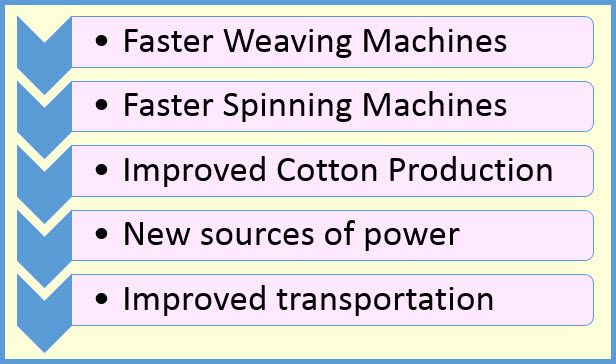

The

changes that snowballed to become the Industrial Revolution began in Great

Britain’s textile industry. Before industrialization, all cloth was

produced by spinners and weavers who worked in their own homes. As a work force consisting mainly of women,

they made wool and linen fabrics, but cotton soon became much more

desirable. It was light, durable and

easy to maintain. Spinners and weavers

were not able to make as much cotton cloth as people wanted to buy. Merchants realized greater profits were

possible if they could find a way to speed up the process.

First

John McKay invented the flying shuttle in 1733, and weavers

were able to double the amount of cloth that they produced. Shortly, spinners were unable to supply

enough thread for the weavers to continue this level of production. John

Hargreaves designed the spinning

jenny to help solve this problem.

One spinner could then form six or eight spools of thread at once. Even bigger changes soon followed. The water

frame, engineered by Richard Arkwright and the spinning mule,

invented by Samuel Compton, used water from fast-flowing

streams to drive the spinning wheels.

Although these machines were capable of producing fine-quality thread,

they were much too big to be housed in small, English cottages. It became more practical to set up several

large machines in buildings called factories.

The

new factories operated with water power, and owners were forced to build them

next to rivers and streams. These

locations often did not provide convenient access to workers, raw materials and

markets. Manufacturers began to search

for new sources of power. Coal mines

were using pumps driven by steam to remove water from shafts, but the engines

developed for this purpose were expensive to operate. James

Watt, an instrument maker from Scotland, acquired financial backing and

began to improve the steam engine. The

result was an efficient, practical power source that could be used anywhere.

STOP: Answer Section D Questions.

Getting

from Here to There

As

production rose, the British industrialists were faced with a new

challenge. How were they going to move

raw materials to their factories and products to their markets? When the Industrial Revolution began, roads

in Great Britain could not handle heavy wagons and were inaccessible in bad

weather. John McAdam, a Scottish engineer, designed a new plan for their

construction by adding a layer of large stones for drainage and by topping it

with an additional section of crushed rock.

Although this was a major improvement, transporting goods by water was

still cheaper. To cut costs even

further, the British built an expanded network of canals that extended water

transportation to even more areas.

An Early Steam Locomotive

However,

steam power soon revolutionized transportation as well as production. In 1804, an English engineer, Richard Trevithick, made an engine that

could pull a cart on a set of rails, and the locomotive was born. Many versions soon followed, and George Stephenson began working on the

world’s first railroad line in northern England. By 1805, trains were carrying coal from the

mines of Yorkshire to the ports of the North Sea along twenty-seven miles of

track. Those who built railroad lines

recognized the advantage of carrying passengers as well as freight. Although they were slow by our modern

standards and broke down frequently, trains were an immediate success. For example, in 1750, it took two weeks to

travel in a carriage from London to Edinburgh.

By 1830, the same 330 mile trip by rail was completed in three days.

The

development of a railway system brought about dramatic changes in British

life. Building bridges and tunnels for

trains resulted in the creation of millions of new jobs. The increased demand for coal and iron

elevated the demand for workers in these areas, too. Many employees were also willing to relocate

since they could easily make regular visits home. Travel for pleasure also became popular, and

seaside resorts gained in popularity.

Those who remained on the farm also profited since progress in

transportation offered new opportunities to expand the markets for meat and

produce.

Arrival of the Normandy Train by Artist Claude Monet

Although

they were a great benefit, trains were far from perfect, and some enterprises

suffered as a result of their expansion.

Many canal operators, for instance, found themselves out of business as

the railroads advanced. Delays and

accidents were common occurrences, and travelers often found themselves covered

in black soot. However, railroads still

proved to be faster and more reliable than the methods of transportation used

in the past. Trains connected factories

to suppliers of raw materials and buyers of finished goods. This enabled the Industrial Revolution to continue

it meteoric growth.

STOP: Answer Section E Questions

The

Spread of Industrialization

No

other country came close to rivaling Great Britain as the undisputed industrial

leader of the age. By 1850, Britain was

producing two-thirds of the world’s coal and one-half of the world’s cotton

cloth. The nation was determined to keep

its edge. For many years, it was illegal

for engineers to leave the country, but their departure proved impossible to

control. Samuel Slater donned a disguise and boarded a ship bound for

America where he built machines from memory.

Other ambitious workers made their way to the European continent and

pockets of industry grew. Belgium, with its supply of coal and

navigable rivers, was one of the first countries to open factories powered by

steam.

Postcard Featuring the Crystal

Palace

Britain’s

unprecedented leadership was obvious in 1851 when the Great Exhibition opened in London’s Crystal Palace. Designed

especially for this event, the iron and glass structure showcased the wonders

of the industrial age. Over six million

visitors watched printing presses turn out thousands of copies in an hour and

cheered a locomotive traveling at sixty miles per hour. Exhibits, including stuffed elephants from

India and fine porcelain from China, demonstrated the far-reaching extent of

the British Empire and the possibilities for the future.

Going

Global

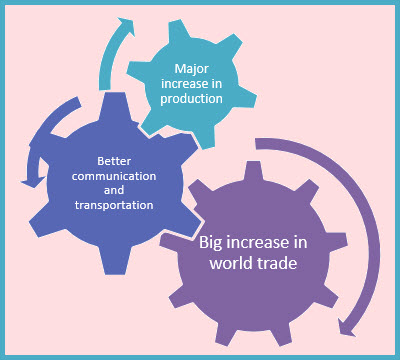

By

the mid-nineteenth century, advancements in transportation and communication

moved beyond Great Britain and onto the world stage. Railroads permeated almost every continent,

and steamships were improving rapidly.

For example, the Transcontinental

Railroad in the United States was completed and carried passengers from New

York to San Francisco in less than a week.

The Suez Canal, which

connected the Mediterranean and Red Seas, opened in 1869 after a decade of

construction. Ships no longer had to

journey around Africa to reach India, and this cut one month off the trip. Communication underwent dramatic changes as

well. By 1850, telegraph lines connected all the major cities in the United

States. The following year, a telegraph

cable was laid under the English Channel creating a connection between Paris

and London.

Financing

railroad and telegraph lines required large amounts of money for investing

known as capital. To raise money, business owners sold shares

of stock in their companies. Everyone who bought stock became an owner in

the company. Stockholders shared the

company’s profits when the business did well and often sold their shares for

more money than they paid for them. Of

course, if the company did poorly, stockholders risked losing their entire

investment. Businesses that functioned

this way became known as corporations

and operated on a greater scale than ever before. These new financial connections and a massive

increase in trade continued to tie the countries of the world together.

STOP: Answer Section F Questions

What

Does It All Mean?

The

Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment inspired more than theoretical and

philosophical changes. They stimulated a

series of rapid changes in industry, transportation and communication that

continue to affect the manner in which we live and work. The spread of industrialism caused people to

respond in a variety of ways, and not everyone agreed on how profits should be

distributed. New methods of doing business

and accumulating wealth motivated countries to adopt a new world view. However, several negative byproducts of

industrial growth also began to emerge.

The quest for greater earnings caused factory owners to neglect the

health and safety of their workers in order to maintain their competitive

edge. Urban growth and a massive influx

of workers from the countryside resulted in overcrowded conditions in the

poorly prepared cities. Disease and

crime were all too common in these settings.

What obligations did businesses have to their workers? What was the role of government in all of

this? How were businessmen going to

continue to increase their profits? We

are still searching for the answers to these questions created by the

Industrial Revolution.

Additional Resources and Activities

When Everything Changed: The Industrial Revolution Article and Quiz