SECESSION AND WAR

SECESSION AND WAR

The Confederate Bombardment of Fort Sumter, 1861

Unit

Overview

As

the country prepared for the presidential election of 1860, the relationship

between the North and the South continued to deteriorate. For many southern whites, it marked a

critical moment. Events at Harper’s

Ferry encouraged fears throughout the South of a slave rebellion led by

northern abolitionists. When the

Republican Party, which included a number of well-known antislavery activists,

took a strong stand against the spread of slavery into the western territories,

southerners saw it as a major threat to their way of life. When Lincoln won the White House, the South

believed that it had no choice but to secede from the Union. Let’s see how it all happened.

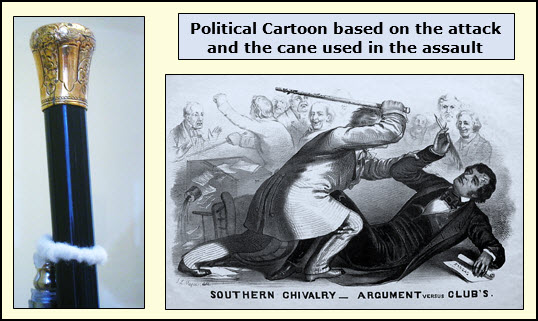

Violence

in the Senate

By

the mid-1850s, Congress found itself deeply divided on the question of

slavery. A growing number of senators

and representatives took extreme positions on the issue. Proslavery and antislavery radicals delivered

fiery speeches on the floor of the House and Senate. Sometimes, they verbally denounced and

insulted their colleagues for their views.

These attacks were often very personal.

In the summer of 1856, anger over these types of statements led to a violent

episode in the U.S. Capitol.

Senator

Charles Sumner, a well-known

abolitionist from Massachusetts, spoke before the Senate and condemned the

actions of the proslavery forces in Kansas.

At the same time, he criticized several southern senators and repeatedly

targeted Senator Andrew Butler of

South Carolina throughout the address.

Two days later, Preston Brooks,

a member of the House of Representatives and Andrew’s cousin, entered the

Senate chamber. He approached Senator

Sumner, who was working at his desk.

Representative Butler drew his cane and struck the unsuspecting senator

over the head. After repeated blows,

Sumner, unconscious and bleeding, fell to the floor. He was hospitalized and did not return to the

Senate for three years. Preston Brooks

was tried in the District of Columbia where he was fined $300.00 but served no

time in jail.

Representative

Brooks resigned from the House of Representatives and gave the citizens of his

home district in South Carolina an opportunity to elect someone else. Although not all southerners approved of his

actions, voters in a special election agreed to return Preston Brooks to

Congress. Newspapers across the country

carried the details of the story, and most Americans formed definite opinions

concerning the Sumner-Brooks affair. Brooks

was a hero to many southerners, who viewed defense of one’s family as

honorable. Most northerners, even those

who were not strong abolitionists, were outraged.

![]() Go to Questions 1 through 3.

Go to Questions 1 through 3.

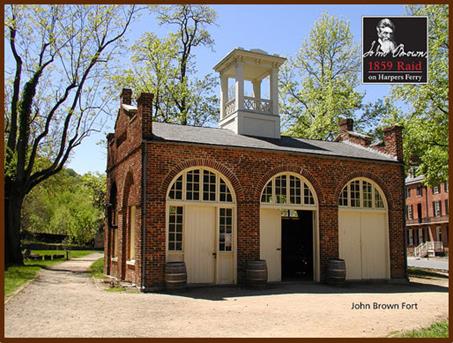

Trouble

at Harper’s Ferry

Bleeding

Kansas and the Brooks-Sumner affair were not the only events that increased the

tension between the North and the South during the late 1850s. Violence also erupted in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, located today in West Virginia. John

Brown, responsible for the deaths of five proslavery supporters in Kansas,

planned to start a widespread slave revolt with the goal of freeing African

Americans in the South. A group of

northern abolitionists gave Brown $4,000 to finance the scheme. On October 16, 1859, John Brown with eighteen

followers put his idea in motion by raiding a federal arsenal in Harper’s

Ferry. Because the structure housed a

large supply of weapons and ammunition, the abolitionist leader hoped to arm

the slaves and to pull off the rebellion.

He and his followers took several hostages and barricaded themselves in

the engine house next to the armory. Learn

more about John Brown’s Raid by watching the video listed below.

To

Brown’s disappointment, his forces were easily defeated. The Virginia militia, federal troops and

local citizens stormed the engine house and captured the raiders. Brown was tried and convicted of murder and

treason. He was executed by hanging for

these crimes on December 2. In the

North, some antislavery supporters, including several influential Republicans,

condemned Brown’s use of violence.

Others, however, called him a hero and a martyr, a term for someone who gave his life for an important

cause. For southerners, the event seemed

to be part of a major conspiracy not only to abolish slavery but to take away

their rights and to ruin their economy.

When they learned that the abolitionists had funded Brown’s plans,

southern anger reached a new level of intensity. Their fury was also directed against the

Republican Party since many northern abolitions were members. As the presidential election of 1860

approached, Americans wondered if it was possible to keep the Union together.

The Engine House at Harper's Ferry National

Park

Go to Questions 4 through 6.

Go to Questions 4 through 6.

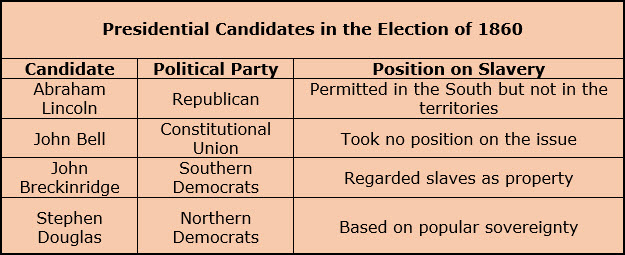

The

Election of 1860

In

the months before the presidential election of 1860, political parties held

conventions and chose their candidates.

Because of disagreements over slavery and the future of the Union, this

was not an easy process. Eventually, the

four candidates, listed in the graphic below, emerged.

On Election

Day, Abraham Lincoln won a clear

majority in the Electoral College and the presidency. When it came to the popular vote, however,

only 40% of the ballots cast were for the Republican contender. Although he won every state in the North,

Lincoln received little support from the Border States and none from the

South. In fact, several southern states

refused to put his name on the ballot. Even though Republicans promised to leave

slavery where it already existed, southerners had no faith in their

pledge. On December 20, South Carolina

called a special convention, and its members approved the secession of the state from the Union.

Go to Questions 7 and 8.

Go to Questions 7 and 8.

A

Last-Minute Compromise?

In

spite of bitter sectional disagreements, some Americans still hoped to preserve

the Union. As South Carolina met to

debate the secession question, congressional leaders in Washington D.C. worked

frantically to hammer out a workable compromise. On December 18, Kentucky Senator John Crittenden suggested the addition

of a group of amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Crittenden’s plan protected slavery by

extending the old Missouri Compromise line across the continent. This was totally unacceptable to Republicans

because they had just won the presidential election by promising to keep

slavery out of all western territories.

Leaders in the South had no interest in discussing any form of

compromise and continued their plans for secession.

Go to Questions 9

Go to Questions 9

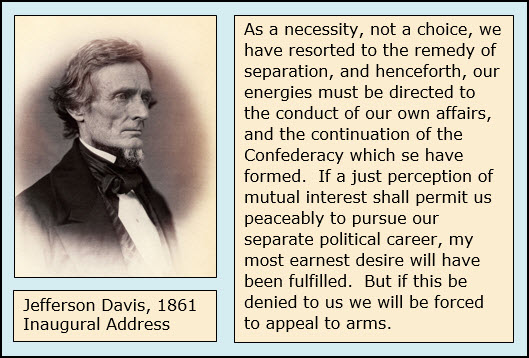

The

Formation of the Confederacy

Alabama,

Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas and Mississippi followed South Carolina’s

example and seceded from the Union in January of 1861. Representatives from these states and South

Carolina assembled in Montgomery, Alabama to form a new nation called the Confederate States of America. They named Jefferson Davis, a former senator from Mississippi, as their

president and wrote a constitution. This

document emphasized states’ rights and legalized slavery. The delegates also justified their right to

leave the Union. They stressed that all

states had become part of the United States voluntarily and should be permitted

to leave voluntarily. The convention

claimed that the U.S. Constitution was a contract and that Congress had

violated that agreement by denying citizens their property or, in other words,

the right to own slaves in all lands controlled by the federal government.

Americans

had mixed reactions to the departure of the southern states. President

Buchanan, who remained in office until Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration on

March 4, sent a message to Congress when the news of South Carolina’s secession

reached Washington D.C. He said that the

southern states had no right to secede but added that he had no power to stop

them. In the South, many citizens

celebrated with parades and parties, but some worried about the

consequences. In the North, a few

determined abolitionists declared that they preferred to see the southern

states leave the Union than to compromise again on slavery. For the most part, however, northerners

believed that the Union had to be preserved even if it required the use of

military force.

People

in all areas of the country anxiously awaited to hear what the new president

would say in his inaugural address.

Would Abraham Lincoln take a hard line in respect to the southern states

or offer gentler tone? In fact, his

speech included both concepts. Lincoln

made it clear that the United States would not accept secession, would hold

onto its properties in the South and would continue to enforce its laws. At the same time, he pleaded with the

southern states to reconsider their decision.

Read an excerpt from Lincoln’s speech quoted in the graphic below.

Go to Questions 10 through 16.

Go to Questions 10 through 16.

Fort

Sumter

The

South soon challenged President Lincoln’s pledge to maintain control of federal

property below the Mason-Dixson Line.

Although Confederate forces seized several forts in the South, Lincoln

did not want to start a war over their capture.

On March 5, 1861, the day following his inauguration, the new president

received a message from Major Robert

Anderson, commander of Fort Sumter, a U.S. military instillation

located on an island off the coast of Charleston,

South Carolina. The dispatch

informed the President that the Confederates had demanded the surrender of the

fort and warned that Union soldiers within the complex were low on

supplies. This put Abraham Lincoln in a

difficult position. If he agreed to the

surrender of the fort, it would appear that he was accepting the South’s right

to secede. A defense of the fort,

however, would likely start a war.

Fort Sumter before the Confederate

Bombardment: 1860

On April

6, President Lincoln contacted Francis

Pickens, South Carolina’s governor, to let him know that unarmed Union

ships carrying necessary supplies would soon be arriving at Fort Sumter. He stressed that the vessels would not unload

additional soldiers or weapons unless the Confederates fired. Governor Pickens advised President Jefferson

Davis and his Cabinet of the situation.

They ordered General P.G.T.

Beauregard, commander of South Carolina’s Confederate troops, to attack

Fort Sumter before the Union ships, already delayed by high seas, arrived. Although they held out for over thirty-three

hours, Major Anderson had little choice but to surrender. On April 14, the American flag over Fort

Sumter was replaced with a Confederate one.

President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to defend the Union. At the same time, Tennessee, Arkansas, North

Carolina and Virginia joined the Confederacy.

The Border States, including Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland and Delaware,

continued to allow slavery but remained in the Union. Nonetheless, their populations were divided

over which side to support. The Civil

War was underway.

![]() Go to Questions17 through 19.

Go to Questions17 through 19.

North

vs South

The

North and the South had significant advantages and disadvantages when the war

began. The North had a larger population

from which to draw soldiers and a better banking system to finance the war

effort. The U.S. Navy remained loyal to

the Union and gave the North the option of blockading southern ports. The North had factories that could produce

uniforms, shoes, blankets and tents. Northern industries included 95% of the

country’s ironworks that were essential for making cannons and railroad

track. Northerners could transport

troops, supplies and food along its 22,000 miles of railroad lines with greater

efficiency than the South, whose railroad network consisted of 9,000

miles. The North also benefitted by

having a strong, national government. The

southern dedication to the principle of states’ rights resulted in a central

government with very little authority.

At times, this made it difficult to conduct the war effectively.

The

South, however, had its strengths. For

the North to win the war, it had to invade the Confederacy, defeat its army and

conquer a hostile population.

Southerners, who were united in their cause, were fighting on their own

land. They knew and understood the

terrain and the climate much better than their northern counterparts. When the war started, the South’s military

leadership was superior to the North’s.

Military training was a tradition for the sons of southern

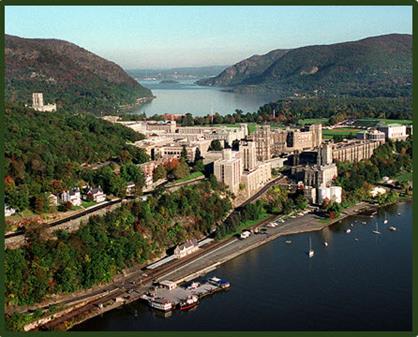

planters. Some chose one of the South’s

seven military academies; others went north to attend the United States

Military Academy at West Point, located in New York’s Hudson River Valley. Although they were officers in the United

States Army, Robert E. Lee, Joseph Johnston, J.E.B. Stuart and other West

Point graduates from the South chose to fight for the Confederacy. Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate

States of America, was also a graduate of West Point and was regarded as a

Mexican War hero. Southerners were quick

to point out that Abraham Lincoln, on the other hand, had served just two

months in the Illinois militia and had seen very little action.

Aerial View of the U.S. Military Academy at

West Point:

Southerners

expected to have the support of Great Britain and other European nations that

purchased their cotton. They believed

that this would give them the edge that they needed to win the war. To emphasize the importance of their product,

they cut off the sale of cotton on the word market in an attempt to shut down

textile factories abroad. Cotton growers

reasoned that unemployed workers would push their governments to support the

Confederacy. In spite of their

advantages and disadvantages, both sides were confident of a quick victory in

1861. The North and the South were

equally unprepared for length and the devastation of the war.

Go to Questions 20 through 25

Go to Questions 20 through 25

What

Happened Next?

When

the American Civil War began, both sides were confident of a quick

victory. By 1862, however, Americans

realized that the conflict would be long and deadly. Before moving on to the next unit, review the

names and terms found in Unit 33; then, answer Questions 26 through 35.

Go to Questions 26 through 35.

Go to Questions 26 through 35.

|

| Unit 33 The Causes of the Civil War |

| Unit 33 The Abolitionists: John Brown |

| Unit 33 What's the Big Idea? Worksheet |