THE ABOLITIONIST

MOVEMENT

THE ABOLITIONIST

MOVEMENT

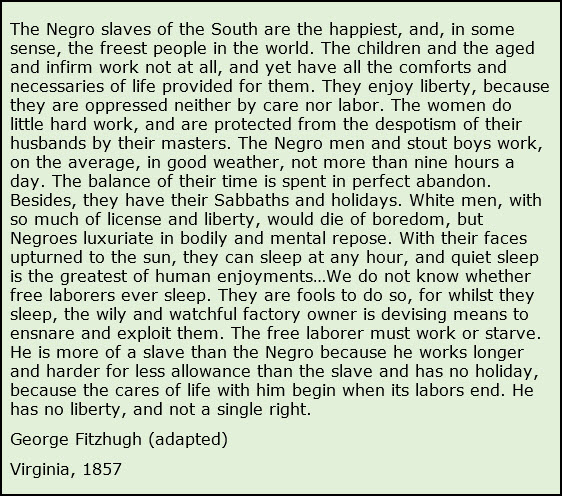

The Underground

Railroad: Charles T. Webber, 1893

Unit

Overview

During

the first half of the 1850s, some northerners expressed concerns about the

quality of life in America. They worked

to improve education, the prison system, the treatment of the mentally ill and

problems related to the consumption of alcohol.

The nation’s most controversial reform movement, however, was the effort

to end slavery. Let’s see how it all

happened.

A

Better America

In

the early 1800s, the Second Great

Awakening, a religious movement, energized American Christians. It began on the frontier with camp meetings

called revivals. Dynamic preachers inspired their listeners to

improve the world along with their personal lives. The Second Great Awakening expanded church

membership, increased the number of missionaries and encouraged an interest in

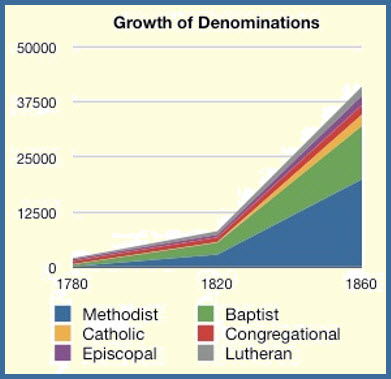

social reform. You can see the growth of

churches for each denomination pictured in the graphic below.

One

problem that drew the attention of nineteenth reformers was the abuse of

alcohol. They claimed that it was

responsible for crime, insanity, poverty and the breakup of families. The demands for temperance, or drinking little or no alcohol, gained momentum with

the formation of the American Society

for the Promotion of Temperance

in 1826. The group held rallies,

distributed pamphlets and delivered lectures concerning the negative effects of

alcohol consumption. Although some

states passed legislation to outlaw the manufacture and sale of alcoholic

beverages, many Americans disliked these laws.

Within a few years, most were canceled or repealed. However, the temperance movement reappeared

in the early 1900s and convinced Congress to propose a constitutional amendment

banning alcohol. Although the amendment

passed, it was overturned in 1933.

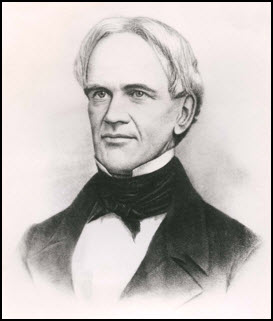

At

the same time, some northerners began working to improve public education and

campaigned for schools supported by tax dollars. The leader of the educational reform movement

was Horace Mann, a Massachusetts

lawyer. He became the head of the

Massachusetts Board of Education in 1837.

While he held this office, the board improved curriculum, lengthened the

school day and doubled teachers’ salaries.

Massachusetts also established a school for training teachers in

1839. Other states soon followed Mann’s

example. By 1860, free public elementary

schools were common in all northern states and several southern cities. On the other hand, public high schools were

rare, but the number of colleges and universities grew rapidly. Although most colleges admitted only men, Mount Holyoke became the first

permanent women’s college in 1837. In

Ohio, Oberlin College, founded in

1833, was open to men, women and free African Americans.

Horace Mann

Concerned

citizens also questioned the living conditions of prisoners and the mentally

ill. Several northern state legislatures

passed laws to assist criminals with their return to society. For example, prisoners

learned trades that would help them to find employment upon their release from

jail. Young offenders were separated

from hardened criminals, and architects designed jails with individual

cells. In some instances, inmates were

not guilty of any crime but were mentally ill.

Dorothea Dix, a Boston

teacher, made it her life’s work to bring this issue to the attention of the

American public. Traveling extensively

throughout the North and the South, she visited prisons and documented the

condition of the insane. She presented

these findings to several state legislatures to secure funds for hospitals and

treatment of the mentally disabled.

![]() Go to

Questions 1 through 5.

Go to

Questions 1 through 5.

The

Question of Slavery

Improving

education and providing appropriate care for the mentally ill were not the only

reform movements that swept the country during the early 1830s. Motivated by the Second Great Awakening and

American ideals, groups of reformers worked to end slavery and to extend the

rights of citizenship to African Americans.

This was not a new idea. Some

Americans had tried to limit or ban slavery before the American Revolution, and

delegates at the Constitutional Convention had debated the issue. Although the practice continued in the South,

most northern states outlawed slavery by the early 1800s. When the British outlawed enslavement

throughout their empire in 1832, American interest in the issue grew.

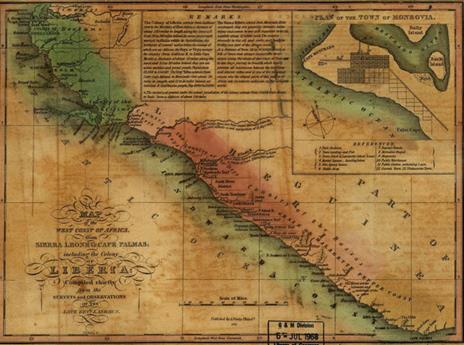

Map of Liberia:

1830

At

first, the antislavery movement focused on resettling African Americans rather

than securing their freedom within the United States. In 1816, the American Colonization Society,

composed of several white Virginians, bought slaves for the purpose of freeing

them and planned to send them out of the country. The organization raised money and purchased

land in West Africa for a colony. By

1822, African Americans arrived to settle in what was called Liberia. Even though Liberia became an independent

country in 1847, it did not attract large numbers of black colonists from

America, and it did not discourage the growth of slavery within the United

States. African Americans, whose

families had lived in the U.S. for several generations, did not want to go to

Africa. They wanted to live as free

people in America.

Other

antislavery reformers in the North concentrated their efforts on convincing

southerners to give up their slaves voluntarily. They suggested that slaves should be freed

gradually to avoid any major disruptions in the economy. Some congressmen considered asking the

federal government to pay owners for the loss of their slaves. This approach, referred to as gradualism, won very little support.

![]() Go to Questions 6 and 7.

Go to Questions 6 and 7.

The

Abolitionists

In

the 1830s, the increased cultivation of cotton made planters in the Deep South

more dependent on slave labor, and the number of enslaved individuals continued

to grow. Reformers, therefore, accepted

that a gradual approach to ending slavery had little chance of success. They took a harder line and called for the

immediate end, or abolition, of

slavery. Americans who held this view

became known as abolitionists.

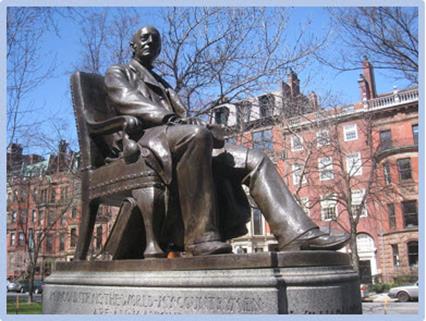

Statue of William Lloyd Garrison: Boston, Massachusetts

One

of the first white abolitionists to demand complete freedom for African

Americans was William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison left Massachusetts in 1829 to work

for an antislavery newspaper printed in Baltimore, Maryland. Because he believed this publication was too

willing to compromise on the slavery question, William Lloyd Garrison returned

to Boston two years later and founded the Liberator, his own antislavery

newspaper. The paper attracted a large

number of readers and led to the establishment of the New England Antislavery Society in 1832 along with the creation of

the American Antislavery Society in

1833. By 1840, over 1,000 chapters of

the American Antislavery Society appeared in towns and cities across the North.

For

free African Americans living in the North, the abolition of slavery was an

important goal. They were proud of their

freedom and wanted to help those who remained enslaved. African Americans took an active role in

organizing the American Antislavery Society and subscribed to the Liberator in large numbers. Following Garrison’s example, Samuel Cornish and John Russwurm

founded Freedom’s Journal, the first U.S. newspaper owned by African

Americans. In 1830, free

African-American leaders held a convention in Philadelphia and discussed ways to

help slaves emigrate from the Deep South.

Learn more about Garrison and other famous abolitionists by watching the

video listed below.

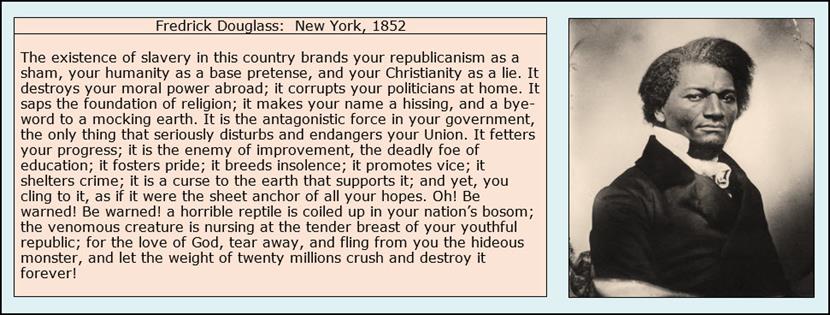

The

best-known African-American abolitionist was Frederick Douglass. Born in

Maryland as a slave, Douglass taught himself to read and write before escaping

to Massachusetts in 1838. Because he was

a runaway, he could have been legally captured and returned to Maryland. Nevertheless, Douglass joined the

Massachusetts Antislavery Society and became a powerful, popular speaker for

the organization’s cause. His

antislavery message reached even more people when he edited a newspaper called

the North

Star. Douglass not only spoke on

the evils of slavery in the United States, but he also delivered lectures in

Great Britain and the West Indies. He

became a free American in 1847 when he purchased his freedom from his former

owner.

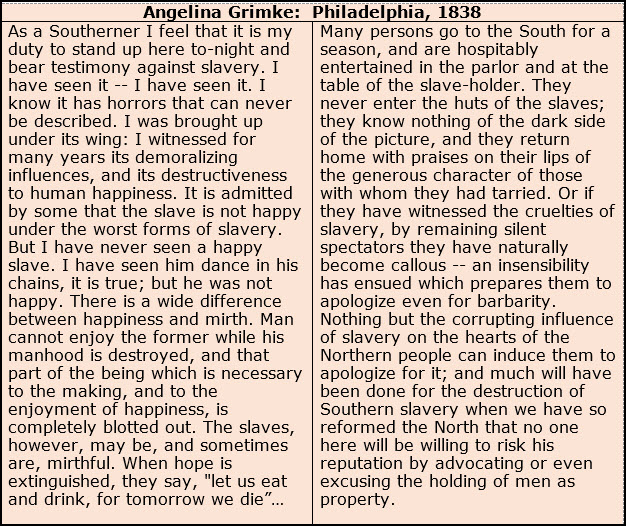

Although

the majority of white southerners defended slavery, a few joined the ranks of

the abolitionists. Among them were Sarah and Angelina Grimke. The sisters, born in South Carolina, were

members of a wealthy, influential family that owned slaves. After the death of their father, they

persuaded their mother to give them their share of the family inheritance. Normally, this consisted of cash or

land. The two women, however, asked for

several slaves whom they, in turn, immediately freed. As expected, they were severely criticized in

their community for this action. Sarah

and Angelina Grimke decided that they could do more for the cause if they moved

to the North so they settled in Philadelphia in 1832. With her husband, Theodore Weld, Angelina published Slavery as It Is, a

collection of first-hand descriptions of life under slavery. It became one of the most influential

abolitionist works of the era. Both

sisters were frequently invited to deliver lectures at antislavery society

meetings. Read an excerpt from one of

these speeches quoted in the graphic below.

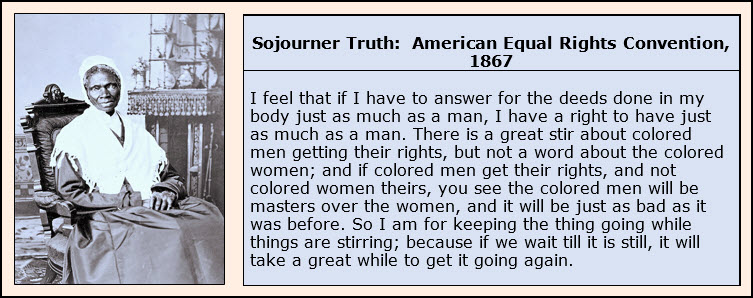

Those

who escaped slavery were often invited to describe their experiences. They gave powerful testimonies about their

lives as enslaved workers. One popular

witness was a women named Sojourner

Truth. She was born a slave in rural

New York in 1797 and given the name Isabella Baumfree. In 1826, Belle escaped, changed her name and

settled in New York City. She worked for

the abolition of slavery and for women’s rights. Part of one of her speeches is quoted in the graphic

below. Making a break for freedom was no

easy task for African Americans living in the South. A few managed to get away to Florida, Mexico

or the Caribbean Islands. Most, however,

dreamed of going north by way of the Underground Railroad.

Go to Questions 8 through 16.

Go to Questions 8 through 16.

The

The

Underground Railroad

Some

abolitionists believed that speaking out against slavery was not enough and

were determined to help African Americans gain their freedom. With this in mind, they established a network

of escape routes between the South and the North. This became known as the Underground Railroad. As you

learned in a previous unit, the Underground Railroad was not underground and

was not an actual railroad. Runaway

slaves, most of whom had never gone more than a few miles from their owner’s

land, traveled on foot at night and relied on the North Star as their

guide. They rested during the day in a

series of barns, church basements and safe houses, referred to as stations. Both black and white abolitionists served as conductors and guided the runaways to

their next destination. They also

provided food and clothing. Some slaves

who made this journey decided to settle in the North, but most hoped to cross

the border into Canada.

The

Underground Railroad was a dangerous activity for everyone involved. The abolitionists broke the law when they

harbored runaway slaves. At the same

time, professional catchers, who were paid to return slaves to their owners,

were a constant threat. Capture resulted

in severe punishment for a slave forced to return to the South. In reality, only a small number of African

Americans successfully escaped through the Underground Railroad, but it

provided hope for millions.

![]() Go to Questions 17 and 18.

Go to Questions 17 and 18.

The

Abolitionists Meet the Opposition

Abolitionist

societies in the North continued to grow, but their members represented only a

small segment of the population. In

fact, most northerners did not support the antislavery movement. They viewed the abolitionists as radicals and

feared their antislavery stance would remove all hope of compromise. Northern industrialists worried that the

national economy would suffer as a result.

Factory workers also resented the abolitionists because they believed

that an influx of freed slaves would lower wages. Others argued that, if freed, African

Americans would never blend into American society.

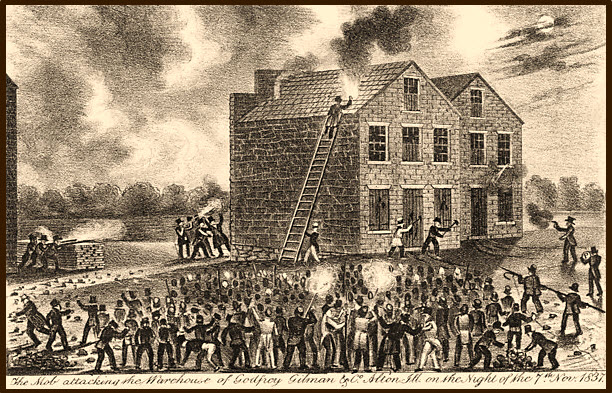

Strong

opposition to the abolitionist movement resulted in violent attacks in a number

of northern cities. A mob burned

Philadelphia’s antislavery headquarters to the ground, and William Lloyd

Garrison had to be rescued in Boston from a hostile crowd that was prepared to

hang him. In Illinois, Elijah Lovejoy’s abolitionist newspaper

office was raided on three separate occasions.

Each time Lovejoy replaced his ruined presses. In a fourth attack, a mob set fire to the

building and killed Lovejoy.

A Mob Attacking Lovejoy's Business

The

abolitionists also drew an angry response from southerners. They insisted that slavery was essential, not

only to the economy of the South but to the financial stability of the nation

as a whole. Slave owners argued that

they treated their slaves much better than northern manufacturers treated their

workers. Planters provided housing,

clothing, medical care and food for their slaves, but factory employees paid

for these necessities out of their own low earnings. Read an example of this line of reasoning

quoted in the graphic below. Southern

anger increased when northern abolitionist groups began to use the U.S. mail to

send antislavery pamphlets to the South.

Mail sacks suspected of containing this type of literature were burned

when they reached post offices in the South.

Most southerners, even if they did not own slaves, remained united

against the abolitionist cause.

Go to Questions 19 through 22.

Go to Questions 19 through 22.

What

Happened Next?

Even

though politicians made an effort to keep the Union together through

compromise, tension mounted between the North and the South throughout the

1850s. The focus of the controversy

shifted to the Great Plains where the Kansas Territory became a battleground

for slavery and antislavery forces.

Southerners connected the violence to the abolitionists and resented the

refusal of some northerners to comply with the Fugitive Slave Law. Before examining the impact of these events

in the next unit, review the names and terms found in Unit 31; then, complete

Questions 23 through 32.

![]() Go to Questions 23 through 32.

Go to Questions 23 through 32.

|

| Unit 31 Frederick Douglass |

| Unit 31 Primary Sources: Conductor on the Underground Railroad Part Two Article and Quiz |

| Unit 31 What's the Big Idea? Worksheet |