THE ECONOMY OF THE

SOUTH

THE ECONOMY OF THE

SOUTH

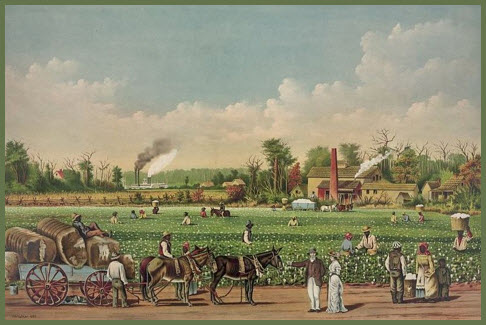

Lithograph of a

Cotton Plantation on the Mississippi River

Unit

Overview

By

the middle of the nineteenth century, the American South had built a thriving

economy, and its wealth was greater than any country in Europe with the

exception of Great Britain.† Unlike the

North, the basis for the regionís financial achievement was agriculture and,

more specifically, the cultivation of cotton.†

However, much of the Southís success was derived from the labor of

enslaved Africans.† Letís see how it all

happened.

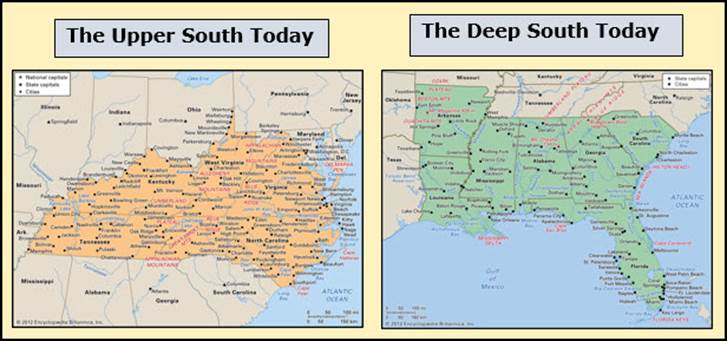

The

Upper and Deep South

In

colonial times, most southerners lived along the eastern seaboard in Maryland,

Virginia, and North Carolina, a region that later became known as the Upper South.† As the number of settlers increased, they

moved beyond the coastal plains into the Deep

South, an area made up of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, South

Carolina and Texas.† Although both the

Upper South and the Deep South relied on agriculture, their economies developed

in different ways.† The Upper South

focused on tobacco, wheat, hemp and vegetables, while the Deep South emphasized

cotton, rice, indigo and sugar cane.†

Movies and novels have encouraged the American public to envision the

South as a series of massive plantations worked by hundreds of slaves.† In reality, some parts of the South included

mountains and forests that were unsuitable for plantation farming.† Less than 1% of southerners kept more than

fifty slaves, and the average property owner was more likely to live in a log

cabin rather than a luxurious mansion.

† Go to Questions 1 through 3.

† Go to Questions 1 through 3.

King

Cotton

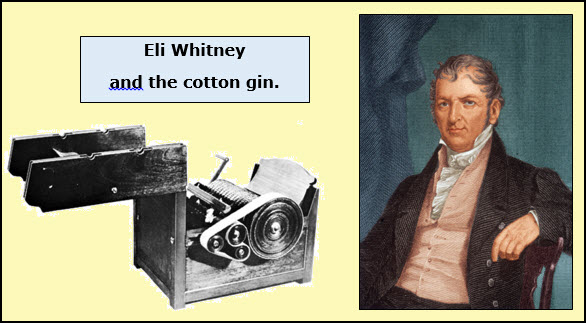

The Industrial Revolution inspired new

textile mills and an interest in machine-made cloth.† This increased the demand for raw cotton

fiber.† Although well-suited to the

climate of the American South, cotton proved to be a difficult crop to prepare

for market.† Cotton plants produced

hundreds of small, sticky seeds that clung to the fibers.† These had to be removed before sending the

cotton to market.† The work was so

tedious that the average worker could only clean about one pound a day.† This changed in 1793 with the invention of

the cotton gin by Eli Whitney.† Using this machine, a worker could clean

fifty pound of cotton per day.† It was

also small enough for one person to carry.†

Plantation owners increased the amount of cotton under cultivation, and

soon the Deep South was producing 60% of the worldís supply.† About 30% of the cotton grown in the U.S.

went to northern factories, while British textile firms purchased most of the

remaining 70%.† By 1860, cotton made up

one-half of the goods exported to foreign countries by the United States.

Like

all property owners, cotton plantation owners had regular expenses, such as the

purchase of seed and equipment.† These

were referred to as fixed costs

since they involved about the same amount of money annually.† Cotton prices, however, were dependent on the

market and varied from season to season.†

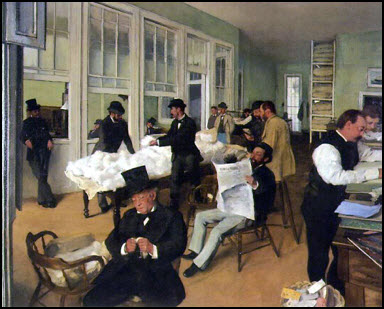

In an attempt to receive the best return, planters sold their cotton to

agents in New Orleans, Charleston and other southern cities.† The agents, who arranged to store the cotton

in warehouses until it reached what was believed to be its highest price,

conducted business in buildings known as cotton

exchanges.† In the meantime, agents

extended credit in the form of loans to the planters.† Because the planters did not receive payment

until the cotton was traded, the majority of southern plantation owners were

continuously in debt.

Cotton Office in the New Orleans Exchange:† Edgar Degas, 1873

Debt

discouraged southern farmers and plantation owners from supporting new taxes

for government-funded projects, such as better roads and public schools.† It also meant that there was less money to

invest in private companies for the construction of canals and railroads.† In 1860, only one-third of the nationís

railroad lines were in the South, and most of them were short runs used to

transport cotton to market.† For the

South, the regionís lack of railroad track would prove to be a major

disadvantage during the Civil War.

† Go to Questions 4 through 8.

† Go to Questions 4 through 8.

Southern

Society

As

in the North, white southern society could be pictured in the shape of a pyramid.† Planters who owned the most land and the most

slaves formed the upper class and represented about 3% of all southern slave

holders.† Although most built homes

comparable to large farm houses, some lived in beautiful mansions and imported

fine furniture from Europe.† They hired

tutors for their children or sent them to boarding school.† Household slaves took care the personal needs

of the planterís family.† Because they

were often in debt, well-to-do plantation owners measured their wealth by the

amount of land they owned, the number of slaves they had and the material goods

they possessed.†

Below

the planters on the social scale were farmers who owned smaller properties and

fewer enslaved Africans.† The majority of

white southerners, about 75% of the population, did not own slaves.† Called yeomen,

they worked their own farms, grew their own food and raised livestock.† Some families rented land for a share of

their crops and labored as tenant farmers.†

The poorest whites cleared what land they could on the edge of the

forests and fed their families by hunting game.†

The Reality

When

a southern property owner died, the land was usually handed down to his oldest

son.† Therefore, younger sons had to

choose other careers or professions.†

Some became lawyers, doctors or military officers; others made a living

as manufacturers.† On a much smaller

scale than their northern counterparts, a few southerners were operating

textile mills, flour-processing companies, lumber yards and iron works by

1860.† For example, Joseph Reid Anderson

took over the Tredegar Iron Works

located near Richmond Virginia in 1840.†

He turned it into one of the nationís leading producers of iron within a

few years.† However, agriculture

continued to be the focus of southern economy and society.

† Go to Questions 9 through 12.

† Go to Questions 9 through 12.

Slavery

in the South

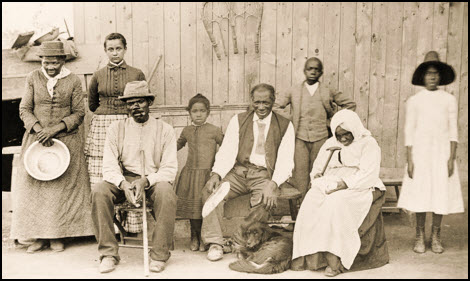

By

the mid-1800s, between 3.5 and 4 million people of African descent lived in the

American South.† In 1808, Congress passed

a federal law prohibiting the slave trade, but this legislation did not outlaw

the buying and selling of slaves within the United States.† As the production of cotton and other cash

crops expanded, the demand for slaves in the Deep South increased.† The price that planters were willing to pay

for slaves also increased.† Slave traders

were determined not to lose out on this opportunity to make profits.† †

Because

they could no longer bring enslaved Africans into the country legally,

professional slave traders had to find new sources for marketable slaves.† Since the children of slaves shared their

parentsí status, they were considered property and were often put up for sale

by their owners.† For African Americans,

the separation of families was one of the most dreaded aspects of slavery.† Another source of marketable slaves was the

Upper South.† Because some areas of

Virginia and Maryland had been farmed in the same way for almost two hundred

years, the soil was wearing out.† It was

no longer economical or practical to keep slaves, and their sales resulted in a

handsome profits.† Therefore, these

farmers chose to sell their slaves rather than to free them.† Slave traders then offered them at auction to

planters in the Deep South.

Slaves Waiting

for Auction:† Painted from a sketch made

in 1853

During

the American Revolution, a small number of enslaved Africans in the South had

been given their freedom.† Most worked

for very low wages at unskilled jobs in southern cities or as farm hands.† A few eventually were able to buy land and

owned slaves.† Sometimes they purchased

members of their families at auction to free them.† The Metoyer

family of Louisiana is a rare example of an African-American ownership of a

large plantation.† They owned thousands

of acres and over 400 slaves.†††

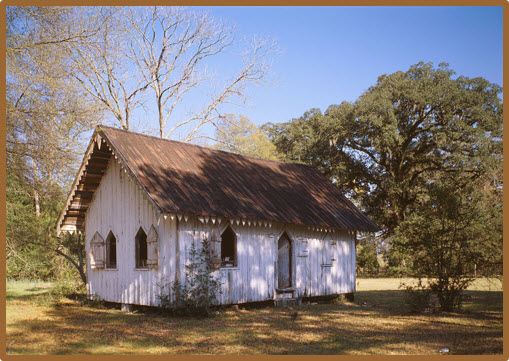

Slave Cabin:†

Arundel Plantation, South Carolina

Even

though they faced hardships and uncertainty, slaves remembered and practiced

many African customs.† They told folk

stories to their children and sang songs from their homeland.† Traditional dances were handed down to new

generations of African Americans.† Many

slaves accepted Christianity, but they also continued to follow the religious

practices of their African ancestors.

† Go to Questions 13 through 15.

† Go to Questions 13 through 15.

Resisting

Slavery

Since

the 1700s, slave owners took threats of rebellion very seriously.† To prevent such an event, most southern

states passed a series of black codes.† These laws became stricter and more numerous

between 1830 and 1860.† Throughout the

South, it was illegal for enslaved Africans to assemble in large groups or to

leave their masterís property without a pass.†

Black codes also made it a crime to teach slaves to read and write,

because white southerners believed these skills made them more likely to

revolt.

In

spite of determination to prevent them, there were anti-slavery

rebellions.† You can learn about several

of them by watching the video listed below.†

The most famous one took place in Virginia in 1831.† Nat

Turner, a religious leader popular among his fellow slaves, led his

followers in a violent attack that resulted in the deaths of fifty-five

whites.† Turner was hanged, and white

southerners imposed even stricter black codes.†

Because most slaves realized that an armed uprisings like Turnerís

Rebellion had little chance of being successful, they looked for other ways to

resist.† Some slaves protested by

performing their tasks very slowly or by pretending to be ill.† Breaking tools and occasionally setting

plantation buildings on fire were also used in attempts to gain some respect

from the white community.

† Go to Questions 16 through 18.

† Go to Questions 16 through 18.

Making

an Escape

Some

slaves hoped to change their lives by running away.† Sometimes this involved short distances to

search for a relative or to escape a harsh master.† A few, however, hoped to gain their freedom

by escaping to the North.† This was a

dangerous and complicated undertaking, especially from the Deep South.† Those who succeeded were mostly from the

Upper South and had help from the Underground

Railroad.† The Underground Railroad

was not underground, and it was not a railroad.†

Operated by free blacks and whites who opposed slavery, it was a network

of escape routes that enabled runaway slaves to move secretly from one safe

house to another.†

Harriet Tubman and a Group of Escaped Slaves

Harriet Tubman was one of the

runaways to complete the journey.† Born a

slave in Maryland, Tubman made her break for freedom when she was thirty years

old.† She returned to the South nineteen times

to help others escape.† Although southern

officials offered a reward for her capture and arrest, she continued her work

and died a free woman at the age of ninety-three.† Her life story is described in the video

listed below.† Unlike Tubman, however,

most runaways were unsuccessful.† When

captured, they faced severe punishments, such as whippings or beatings.†

![]() †

Harriet Tubman and her Escape to Freedom

†

Harriet Tubman and her Escape to Freedom

† Go to Questions 19 and 20.was

† Go to Questions 19 and 20.was

What

Happened Next?

During

the first half of the nineteenth century, a growing number of Americans decided

that slavery was wrong.† They formed

societies to support their cause and demanded change.† The anti-slavery movement drew sharp

criticism from not only southerners but from northern factory workers, who

feared that an influx of former slaves would threaten their jobs.† Could the issue of slavery be resolved?† Did the anti-slavery movement actually help

enslaved people?† Before moving on to

explore these topics in the next unit, review the names and terms found in Unit

30; then, answer Questions 21 through 30.

† Go to Questions 21 through 30.

† Go to Questions 21 through 30.

|

| Unit 30 The Underground Railroad |

| Unit 30 Mount Vernon and the Dilemma of a Revolutionary Slave Holder Article and Quiz |

| Unit 30 What's the Big Idea? Worksheet |