THE ECONOMY OF THE

NORTH

THE ECONOMY OF THE

NORTH

U.S.

Postage Stamp Commemorating the Anniversary of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Unit

Overview

Although

Americans took great pride in their victory over Mexico, the sectional rivalry

between the North and the South continued to intensify.† Because they built different economies, both

regions were determined to protect their interests.† In the North, advancements in technology,

transportation and communication encouraged the development of new industries

and the expansion of established ones.†

During the 1850s, the population of the northeast grew rapidly due to

the ongoing arrival of large numbers of immigrants.† They provided a ready supply of cheap labor

in the factories but were often subjected to discrimination and prejudice.† African-Americans living in the North also

faced unfair treatment and were denied the right to vote in most states.† Letís see how it all happened.†

Northern

Society

Although

many northern industries made large profits by the mid-nineteenth century, the

regionís wealth was not equally distributed.†

The upper class made up 10%

of the Northís population, but its members owned 40% of the entire nationís

assets.† This elite group included

bankers, shippers, manufacturers and merchants.†

They owned factories, mines, railroads and other advantageous

businesses. †Their families vacationed in

Europe, belonged to exclusive social clubs and attended college, a privilege

available to only about 1% of Americans at that time.† Many upper-class northerners maintained

mansions in the city and at the seashore or in the mountains.

Going to the Opera:† Seymour Joseph Guy, 1874

About

40% of the Northís citizens belonged to the middle class.† It mainly

consisted of small-business owners, lawyers, doctors, religious leaders and

farmers who owned land.† Members

belonging to this social category generally enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle and

were able to afford the newest conveniences, such as indoor plumbing and central

heat.† Those who could finance it often

sent their children to private schools with the hope of making connections with

the upper class.†

The lower class composed the remaining 50%

of the Northís society.† Agricultural

workers that did not own property and manual laborers in factories were part of

this group.† For the most part, they had

little control over their working conditions, salaries or hours.† Most put in twelve or fourteen hours daily

six days a week.† Industrial accidents

were common, and those injured on the job were simply fired.† Children of lower-class families often went

to work at an early age.† This left them

little time for school or play.† Without

training or education, most were destined to earn low wages and had few

opportunities to escape poverty.

A Young Textile Worker in New Hampshire

In

the 1830s, factory employees began organizing and demanded better

conditions.† Groups of skilled workers

involved in the same trades formed trade

unions, such as the General Trades

Union of New York.† Unskilled workers

followed their example.† To put pressure

on employers for higher wages and shorter work days, workers engaged in strikes.† During a strike, employees refused to work

and tried to disrupt production or service.†

Strikes were illegal in the early 1800s, and workers were fired for

participating in them.† However, a

Massachusetts court ruled in 1842 that workers did have a right to carry out

these activities.† Nonetheless, many

years passed before a workerís right to strike was actually respected.

![]() † Go to Questions 1 through 6.

† Go to Questions 1 through 6.

A

Growing Population

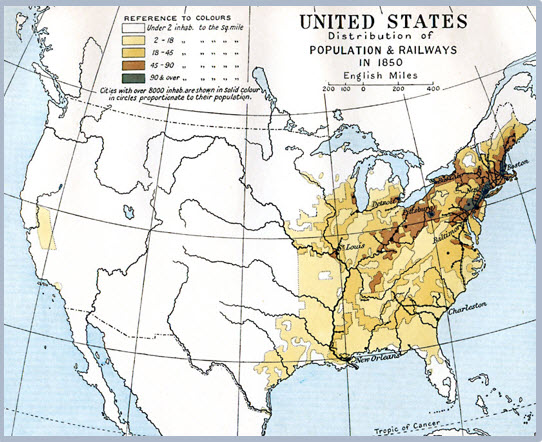

Between

1845 and 1860, the number of immigrants entering the United States steadily

increased.† American manufacturers in the

Northeast welcomed the new arrivals because many of them were willing to work

long hours for little pay.† By 1860, the

population of the twenty-three states that defined themselves as the North was

21 million.† The southern states, on the

other hand, accounted for a little over 9 million people, 3.5 of which were

enslaved Africans.† The map below shows

the population distribution throughout the United States in 1850.

Map Courtesy of FCIT and the Roy Winkelman Collection

The

largest group of immigrants came from Ireland.† A census taken in 1850 noted that there were

961,179 people in the United States that were born in Ireland.† That number exceeded 1.5 million by

1860.† Irish immigrants lived primarily

in New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Ohio and New Jersey.† The men found jobs in factories, in coal

mines and on railroads.† Women accounted

for nearly half of the Irish who came to America.† Some found employment in industry; others

worked as maids, cooks and nannies in the households of the upper class.† The video listed below explains more about

the arrival of these future Americans and their impact.

![]() † Go to Questions 7 through 10.

† Go to Questions 7 through 10.

Prejudice

and Discrimination

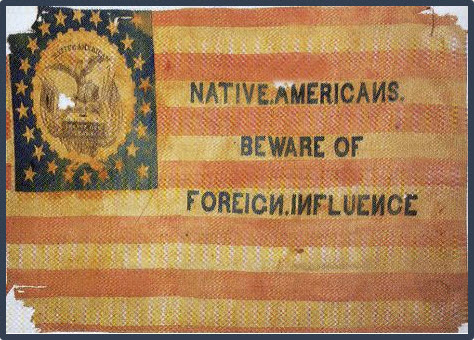

Immigrants

brought with them their languages, religions, customs and ways of life.† Many of their practices eventually became

part of American culture, but some viewed immigration as a threat to the

futures of native, or American-born, citizens.†

Those who opposed the arrival of large numbers of foreigners were called

nativists.† Because many immigrants accepted low

salaries, the nativists often blamed them for keeping wages low.† They also claimed that foreigners increased

crime and disease in cities like New York and Boston.

The

anti-immigration sentiment led to the formation of the American Party.† When asked

about their organization, members frequently responded by saying, ďI know

nothing.Ē† Therefore, the group became known

as the Know-Nothing Party.† The Know-Nothings campaigned for stricter

immigration laws and tried to ban foreign-born citizens from running for public

office.† However, the movement collapsed

when the party split over the issue of slavery.

Flag

of the Know Nothing Party:† 1850

Free

African Americans living in the North were also subjected to prejudice and

discrimination.† Although slavery had

been outlawed by most northern states by 1830, African Americans were generally

denied the right to vote in public elections.†

Communities did not permit them to use public facilities and demanded

that they have separate hospitals and schools.†

The overwhelming majority of African Americans living in the North were

extremely poor.† However, there were some

notable exceptions.† In 1845, for

example, Macon B. Allen became the

first African American in the United States to practice law.† Henry

Boyd established his own furniture-manufacturing company in Cincinnati,

Ohio, while John B. Russwurm and Samuel Cornish founded Freedomís

Journal, the countryís first African-American newspaper in New York

City.† At the same time, abolitionist, or anti-slavery,

organizations formed in many cities and towns throughout the North.† These societies included black and white

members who hoped to end the practice of slavery in all regions of the United

States.†

![]() †† Go to

Questions 11 through 13.

†† Go to

Questions 11 through 13.

Connecting

North and West

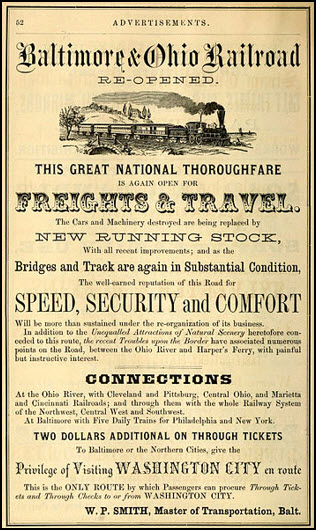

Although

better roads and canals improved transportation in the United States, northern manufactures

and mid-west farmers continued to look for cheaper, faster ways to exchange

goods.† Following the British example,

Americans began experimenting with railroads in the 1830s.† The Baltimore

and Ohio was the first U.S. railroad line.†

It offered regular passenger service along a thirteen-mile track with

carriages pulled by horses.† Tom

Thumb, the first American steam locomotive, was designed and built by Peter Cooper.† Although it quit working in its first race

with a horse-drawn train, steam locomotives quickly became a reliable source of

power.† Soon a railway network connected

the major cities in the Northeast and stretched into the Midwest.† Grain, dairy products and livestock moved

from mid-west farms to the cities along the eastern seaboard.† Because manufactured goods traveled faster

and more cheaply by train, producers offered lower prices.† This made their products more affordable for

settlers in the West.

Poster for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Canals

and railroads engaged in a bitter competition for customers, but the railroads

proved superior in service.† They could

be built anywhere and could operate year-round.†

In 1840, the United States had 3000 miles of railroad track.† By 1860, 31,000 miles of track, mostly in the

North and Midwest, had been built.† In

1869, railroad companies completed the transcontinental railroad line, which

ran from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast.

Samuel Morse and a Telegraph Receiver

Faster

travel inspired faster communication.† Samuel Morse, an American inventor,

developed the electric telegraph.† For

the alphabet, he substituted a code of dots and dashes that could be typed and

transferred through a network of telegraph wires.† In 1837, he demonstrated his idea by typing a

message from a terminal in Washington D.C.†

A few moments later, an operator in Baltimore sent the same message to Morse

as a reply.† Soon words were flying back

and forth between the two cities.†

Americans immediately formed telegraph companies and strung telegraph

wires across the country.† Newspapers

used the telegraph to send stories over great distances.† Information that once took weeks to travel

from East to West arrived in a few moments.†

For example, election results were spread rapidly across the country

with the telegraph.† Railroads were able

to send information concerning delays or changes in schedules to train stations

along their lines.

† Go to Questions 14 through 17.

† Go to Questions 14 through 17.

Revolutionizing

Farming

As

railroads provided farmers with access to more markets for their crops,

mechanized farming equipment offered the ability to increase the size of their

harvests.† When they first came to the

Great Plains, settlers feared that their wooden plows were not strong enough to

break up the sod for planting.† John Deere solved this problem in 1837

with the invention of the steel-tipped plow.†

This sturdy, metal tool easily cut through the hard-packed soil and

simplified the sowing of wheat, a grain that grew in abundance once it took

root.

A Re-enactment of the Use of the McCormick Reaper

Traditionally,

farmers had harvested their crop by cutting it with handheld sickles.† This was a slow, time-consuming task.† It also limited the amount of wheat that a

farmer could manage.† That changed when Cyrus McCormick designed and built the

mechanized reaper.† This invention

enabled a single farmer to cut more wheat than five farmers working by hand.† Learn more about the impact of technology on

the lives of Americans by watching the video below.

![]() †

Technological Developments during the Jacksonian Era

†

Technological Developments during the Jacksonian Era

Settlers

on the prairie were able to grow wheat for shipment as a cash crop to the

Northeast.† Then, farmers in the

Northeast concentrated on growing fruits and vegetables, products that were

better suited to the regionís soil and climate.†

These changes resulted in what has been called the Marketing Revolution.† Learn

more about its effect on the American economy by watching the video listed

below.

The

new economy had both positive and negative results.† Although farmers and factory owners profited

from the growth of agriculture and manufacturing, there were sometimes severe

economic downturns and heavy losses.†

Farmers were dependent on weather conditions and had no control over the

fees charged by the railroads.† A lack of

government regulation left workers and small business owners at the mercy of

wealthy industrialists.† By the 1930s,

reliance on wheat as the cash crop of the Great Plains had destroyed the areaís

system of natural grasses.† This was a

major factor in creating the Dust Bowl, an ecological disaster that took years

to correct.

† Go to Questions 18 through 20.

† Go to Questions 18 through 20.

What

Happened Next?

The

economy of the South also prospered between 1820 and 1860.† A boom in cotton sales made agriculture

profitable, and most southerners believed that the trend would continue.† To meet the demand, planters increased their

reliance on slave labor and were determined to continue the practice of

slavery.† Before examining the economy of

the southern states in the following unit, review the names and terms in Unit

29; then, complete Questions 21 through 30.

† Go to Questions 21 through 30.

† Go to Questions 21 through 30.

†† †††

|

| Unit 29 Railroad History |

| Unit 29 The Irish Immegrant Experience Article and Quiz |

| Unit 29 What's the Big Idea? Worksheet |