FOREIGN

EXPANSION AND THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR

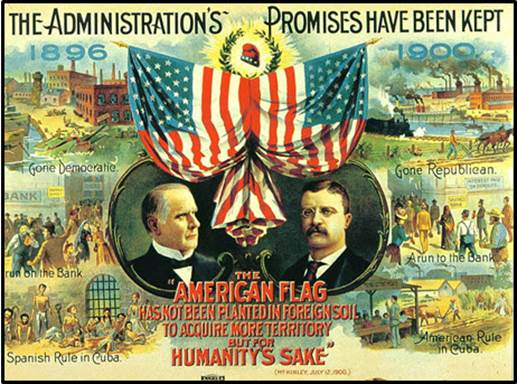

McKinley-Roosevelt Campaign

Poster: 1900

Unit Overview

American industrial growth in the late 1800s

encouraged an interest in overseas expansion and the quest for new

markets. The successful outcome of the

Spanish-American War elevated the United States to a position of global

leadership and encouraged a sense of cultural superiority. The acquisition of Hawaii, the Philippines,

Guam and Puerto Rico along with the construction of the Panama Canal reinforced

this new image. Even though there was

widespread support for these policies, some Americans saw these imperialistic

ventures as a betrayal of the nation’s democratic principles. Let’s see how it all happened.

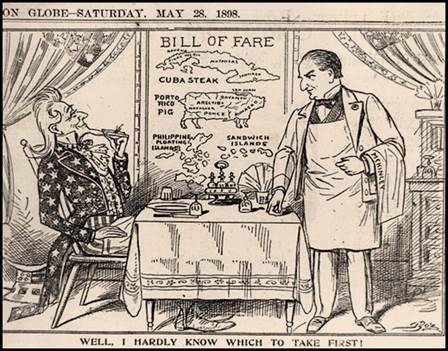

Political Cartoon from the

Boston Globe: 1898

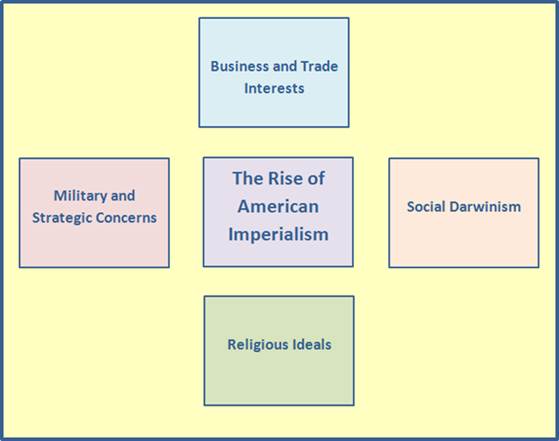

The Path to American Imperialism

During the decades after the Civil War, the United

States became the most productive industrialized nation in the world, but it

was not regarded as a military or diplomatic leader on the world stage. Even though American manufacturing firms had

surpassed British companies with their output, Great Britain maintained an army

that was five times larger and a navy with ten times more sailors than its

American counterparts. The United States

enjoyed the luxury of being surrounded by two oceans and countries that were

usually considered non-threatening.

While European nations extended their economic, political and military

control over weaker territories through a practice known as imperialism, most Americans viewed this

policy as inconsistent with their democratic principles and had little interest

in overseas expansion.

By 1890, the attitude toward dominating regions

outside of U.S. borders had changed.

Since over one-fourth of the country’s farm products and one-half of its

oil were shipped abroad, American industrialists recognized the importance of

gaining new markets for their goods and access to raw materials. A popular theory of the era, social Darwinism, suggested that the

world’s nations were engaged in a struggle for survival and that those who

failed to compete were destined to decline.

This led some American citizens to conclude that, if the United States

did not become more aggressive in the realm of foreign affairs, the country

would be left out and left behind. This

anxiety was compounded by the nation’s population growth and the decrease in

available land for more settlers in the western part of the continental United

States.

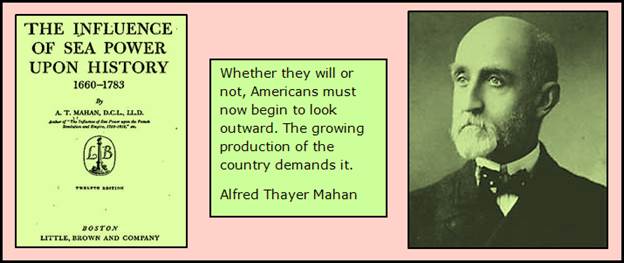

The

turn-of-the-century American public was also convinced that a powerful military

presence was an essential component of economic prosperity. The Influence of Sea Power upon History,

a popular book written by naval strategist Alfred

Thayer Mahan, stressed the importance of controlling the world’s sea

routes. His theories led the United

States, Germany and Japan to replace their wooden sailing vessels with steel

ships fired by coal or oil. If the

industrialized countries of the West were to tap into lucrative Asian markets,

naval bases and refueling stations had to be established on the islands in the

Pacific Ocean. U.S. political leaders

believed that this required a new and improved navy. To back up claims that America had become a

major sea power, President Theodore

Roosevelt ordered sixteen battleships, nicknamed the Great White Fleet, to circumnavigate the globe in 1907. A strong naval presence in the Pacific also

encouraged Americans, especially Christian missionaries, to travel to the Far

East. By 1890, over five hundred mission

centers had been established in China alone.

Go

to Questions 1 through 6.

The

Annexation of Hawaii

Americans and Europeans first became aware of the

Hawaiian Islands through first-hand accounts from British explorer and

cartographer Captain James Cook in

1778. Missionaries from the United

States arrived on the islands in 1820 followed by planters, who established

sugar and pineapple plantations. In a

short time, the islands’ sugar producers were selling over $20 million worth of

sugar to the United States annually, but action taken by the U.S. Congress on

behalf of domestic growers threatened this prosperous business. In 1890, the passage of the McKinley tariff

changed the American policy on the importation of sugar. This tax made it cheaper for American

households to buy sugar produced within the country. U.S. companies growing sugar cane in Hawaii

quickly realized that their profits would decline unless the islands became part

of the United States.

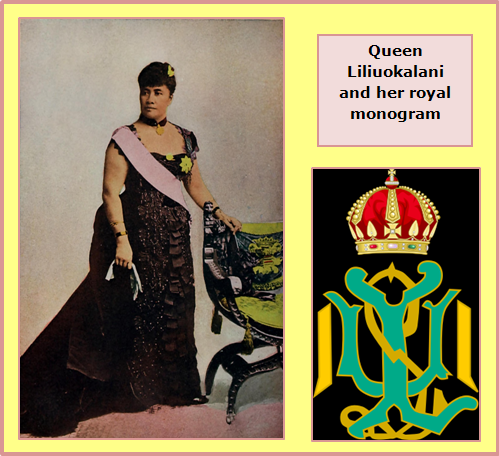

Meanwhile,

Hawaii’s ruling monarch, Queen Liliuokalani,

believed that American business interests had grown too powerful and too

influential; the Queen was determined to return control of the economy to

native Hawaiians. In response, Americans

who owned pineapple and sugar farms organized to overthrow the government with

the help of John L. Stevens, the official

U.S. representative to the Hawaiian Islands.

Backed by American soldiers, they imprisoned the Queen and seized 1.75

million acres of royal land. Liliuokalani

relinquished her throne to prevent bloodshed and called upon the United States

government to restore her authority.

When they lobbied Congress to annex Hawaii, the rebels insisted that

they had brought down a corrupt regime and advanced the principles of

democracy. In agreement, the American

military pointed out the value of Hawaii as a naval base. Although the issue was the subject of a

heated congressional debate, a joint resolution of Congress ensured the

annexation of Hawaii, and the islands became a United States territory in 1898.

Go

to Questions 7 and 8.

The

Spanish-American War

The nineteenth century saw the decline of Spain’s vast

empire that had once spanned both North and South America. As the period drew to a close, the most

important colony still under Spanish control was Cuba, and the island’s major cash crop was raw sugar. Ninety percent of that harvest was shipped to

the United States to be refined and marketed.

This put Cuba at the mercy of the U.S. economy. The cancellation of a major trade agreement

between the United States and Cuba’s colonial government set off a violent

revolution against Spanish rule in 1895.

Spain responded with a series of harsh countermeasures to put down the

rebellion. American newspapers sent

journalists to cover the story, but, since the fighting took place in the

remote regions of the island, the correspondents relied on second-hand

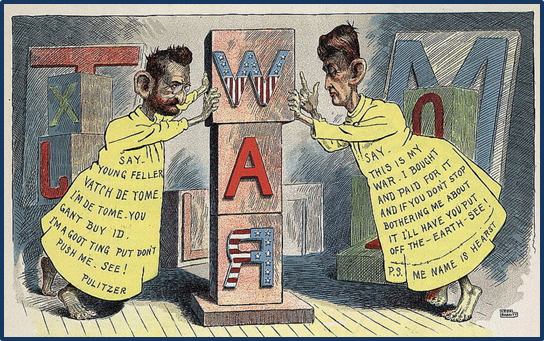

information and undocumented reports of Spanish atrocities. The New

York American published by William

Randolph Hearst and The New York

World, under the direction of Joseph

Pulitzer, engaged in a battle for circulation; both men printed stories to

sell papers rather than to provide accurate information to the public. This

style of reporting, which emphasized sensationalism and often ignored facts,

became known as yellow journalism.

Political cartoon showing the competition between Hearst and Pulitzer

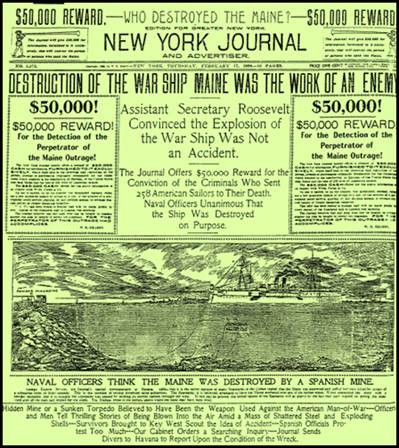

Public

opinion demanded support for the Cuban rebels, and businessmen pushed the

federal government to prevent the destruction of American-owned sugar

plantations. In response to these

demands, President McKinley ordered the U.S.S. Maine into the region to

protect U.S. lives and property. The Maine steamed into the harbor at Havana,

dropped anchor and maintained an American presence. On February 15, 1898, an explosion destroyed

the battleship and killed over 250 sailors.

A U.S. naval court of inquiry attributed the blast to a submarine mine. Although research later indicated that an

accidental fire was the root cause of the disaster, the majority of Americans

blamed Spain. President McKinley wanted

to avoid a war, but he also knew that his opposition could lead to the loss of

a second term. Spain also preferred a

peaceful settlement with the United States but would not give in on the demand

for Cuban independence. McKinley asked

Congress for a declaration of war on April 11, 1898, and Congress complied

eight days later. At the same time,

Congress also passed the Teller

Amendment which specified that the United States had no desire to take over

Cuba and was not interested in adding it to the United States as a territory.

American

troops began to arrive in Santiago

in June of 1898 and fought the Spanish forces in the hills overlooking this

Cuban city. The key battle took place on

July 1 when the Rough Riders, led by

Theodore Roosevelt, took San Juan Hill.

Four African-American regiments led the frontal assault and, in spite of

heavy casualties, drove back the Spaniards.

On July 3, American naval forces destroyed the Spanish fleet anchored in

Santiago’s harbor, and this victory was followed by Spain’s surrender two weeks

later. U.S. troops also landed in Puerto Rico, the last Caribbean island

held by Spain. Spanish officials there

yielded to the Americans without a fight.

An armistice was arranged to end the conflict on August 12, 1898. Spain agreed to liberate Cuba and to cede to

the United States Puerto Rico. The

United States also gained possession of Wake and Guam, small islands located in

the Pacific. The final peace treaty

would have to wait unit the two sides settled the issues on the Spanish-American

War’s other front, the Philippines.

Go

the Questions 9 through 13.

The

Philippines

Clashes

between Spain and the United States were just not confined to the Caribbean

during the Spanish-American War. The

Philippines consisted of an archipelago of over 7000 islands and was part of

Spain’s colonial empire. The U.S. Navy

knew that part of the Spanish fleet was anchored in Manila Bay and instructed Admiral George Dewey, commander of the

Pacific fleet, to set sail for that harbor if war broke out. The Americans also arranged for Emilio Aguinaldo, who had led the fight

for Philippine liberation from Spain before his exile, to return to his home

country. Believing that the United

States supported independence for the island nation, Aguinaldo agreed to help

defeat the Spanish. On May 1, Dewey’s

squadron destroyed the Spanish ships and went on to capture the capital city of

Manila by mid-August.

Colored print picturing Dewey at the Battle of Manila Bay

The

victory touched off an intense debate in the United States concerning the

future of the Philippines. That America

should become a colonial power in the European tradition was out of the

question. Several senators only wanted

to keep Luzon, the island on which Manila was located, and to divide the

remaining islands among the European powers.

President McKinley argued that this plan handed over valuable seaports

to other industrialized countries competing with the Americans for foreign

markets. There was also some discussion

of granting independence to the Filipinos, but this idea had little support

since most Americans believed that they were not prepared to govern

themselves. This was a major disappointment

to Emilio Aguinaldo and others who had expected self-government. They retaliated against American occupation

by the tactics of guerrilla warfare, and the U.S. Army responded by raiding

villages and carrying out indiscriminate attacks. The insurrection ended in 1902, but the

United States did not grant independence to the Philippines until 1946.

Go

to Questions 14 through 16.

The Open Door Policy

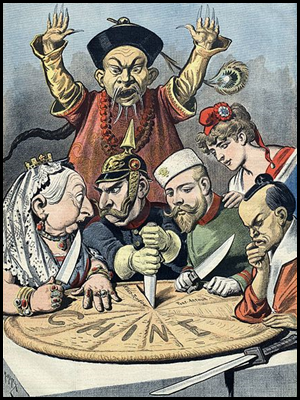

With

the acquisition of Hawaii, Guam and the Philippines, the United States had

established the stepping stones across the Pacific to the Chinese markets. By the late 1890s, China had been weakened by

internal conflicts and was unable to resist the foreign powers that wanted to

exploit her natural resources and commercial prospects. Japan, Russia, Great Britain, France and

Germany had already claimed spheres of

influence or areas in China where each nation had special privileges and

exclusive trading rights. Fearing that

American products would be shut out, Secretary of State John Hay proposed the Open Door Policy, which called for all

nations to respect the territorial integrity of China and to permit equal trade

access. He explained the idea in a

series of diplomatic notes and received only vague or evasive replies.

Political cartoon symbolizing

the policies of Great Britain, Germany, Russia, France and Japan

Some

Chinese were frustrated by the arrogance of those foreigners who came to China

only to further their own commercial interests.

A secret club, called the Boxers,

expressed their anti-foreign sentiments by committing random acts of

violence. This eventually led to a

full-scale revolt known as the Boxer

Rebellion. The rebels succeeded in

trapping hundreds of foreigners in the capital city of Beijing and holding them

hostage. They were rescued by a combined

military force from several nations, including the United States. The Boxer Rebellion caused Americans to fear

that Europeans might seek revenge and make their spheres of influence even more

exclusive. This would make it more

difficult to sell U.S. products in China.

With this in mind, Secretary Hay sent out a new set of notes that

stressed the importance of preserving China’s independence. Although the Open Door Policy did not turn

out to be an economic victory for the United States, it did emphasize the American

determination to increase its foreign trade and the desire to play a larger

role in world affairs.

Go

to Questions 17 and 18.

The

Panama Canal

Because

the Spanish-American War had been fought in both the Caribbean and the Pacific,

pressure to build a canal through Central America increased. The idea also appealed to U.S. industrialists

who wanted to eliminate the transportation coats generated by the long route

around South America. In 1901, President

Theodore Roosevelt opened negotiations with Columbia to lease the province of Panama for this venture.

When the Columbian legislature turned down the proposed treaty,

Roosevelt gave covert assistance to the growing independence movement in

Panama. Following a bloodless

revolution, the United States recognized the new country on November 13,

1903. Two weeks later, the United States

had a new lease on a canal zone and eventually paid Columbia $25 million to

cover its losses. The construction of

the Panama Canal is considered one

of the greatest engineering accomplishments of the twentieth century. The project involved clearing acres of swamp

land, moving 240 cubic yards of dirt and building a series of huge locks. It took the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and

thousands of laborers eight years to complete.

When the canal officially opened in 1914, the United States had secured

a dominating strategic and commercial position in the Western Hemisphere.

Go

to Questions 19 and 20.

What’s

Next?

Even

though the United States had tried to avoid an involvement in European affairs

in the past, its emergence as a world leader now made this impossible. In 1917, American soldiers found themselves fighting

on foreign battlefields to win an Allied victory in the Great War. Although World War I would prove to be a

brutal conflict, establishing a long-term peace was another formidable

challenge. Before moving on to examine

these events, review the information in this unit; then, complete Questions 21

through 30.

Go

to Questions 21 through 30.