ANDREW JACKSON AND

THE PRESIDENCY: PART 1

ANDREW JACKSON AND

THE PRESIDENCY: PART 1

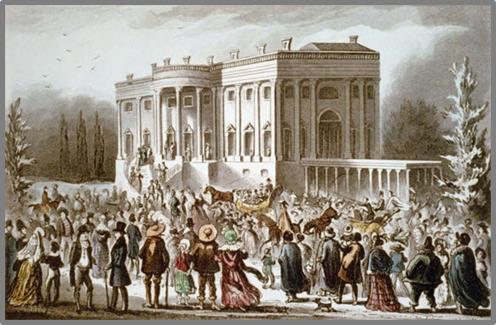

Drawing of the

Scene at the White House after Jackson's First Inaugural: The Playfair Papers, 1841

Unit

Overview

The

election of 1824 proved that the Era of Good Feelings was over. Although Andrew Jackson won the popular vote,

he did not receive the majority required by the Electoral College. This left the decision of who would be

president up to the House of Representatives.

When members of the House chose John Quincy Adams, Jackson was

furious. With the help of Martin Van

Buren, he formed the Democratic Party which carried him to victory in

1828. Jackson brought a new style to the

White House and based his decisions on his definition of democracy. Let’s see how it all happened.

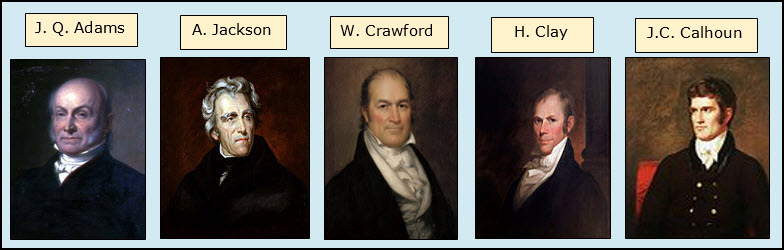

The

Controversial Election of 1824

By

the time James Monroe finished his second term, the Federalist Party had all

but disappeared, and most Americans considered themselves Republicans. There were, however, differences among the

various groups within the party, and four candidates for the presidential

election of 1824 emerged from the three major sections of the country. Although they all called themselves

Republicans, each one had a different opinion on the role of the federal

government. Let’s meet the candidates!

·

Henry Clay: Henry Clay, Speaker of the House of

Representatives and a congressmen from Kentucky, called for a federally funded

program of internal improvements, including roads and canals. According to Clay, this would improve and

increase the exchange of western farm products for eastern manufactured

goods. He favored a national banking

system and supported high tariffs on imported goods to protect American

manufacturers. Henry Clay called his economic

plans the American System and was a

favorite of some western voters.

·

John Quincy Adams: John Quincy Adams, son of former President

John Adams, received the support of the merchants and factory owners throughout

the northeast. Having served as

President Monroe’s capable secretary of state, Adams had foreign policy

experience and proposed measures that strengthened the country as a whole.

·

Andrew

Jackson: Andrew Jackson

briefly served his home state of Tennessee in the House of Representatives and

the Senate, but he was not a Washington career-politician. Born in the Carolina back country in 1767,

Jackson was raised in poverty and was an orphan at age fourteen. He eventually became a wealthy planter and

slave-owner. Unlike the other candidates

in the election of 1824, Andrew Jackson was not just a sectional hero but a

national one as result of his success in the Battle of New Orleans. He refused to take a stand on most issues during

the campaign, because he did not want to risk losing votes.

·

John C. Calhoun: John C. Calhoun had served as a congressman,

vice president, secretary of war and secretary of state. Once a nationalist, he became a strong

supporter of states’ rights by the 1820s.

He opposed high tariffs and claimed that the only protected the

inefficiency of manufacturers. Because

most southerners supported Crawford, Calhoun dropped out of the race for

president and ran for vice president.

Since he was the only candidate for that office, he was assured a

victory.

·

William Crawford: William Crawford, a former congressman from

Georgia and secretary of the treasury during the Monroe administration, was the

nominee of the Republican Party. Former

Presidents Jefferson, Madison and Monroe supported his candidacy. Although Crawford was well-known throughout

the South, he suffered a stroke, and his ill-health limited his ability to

conduct a convincing campaign.

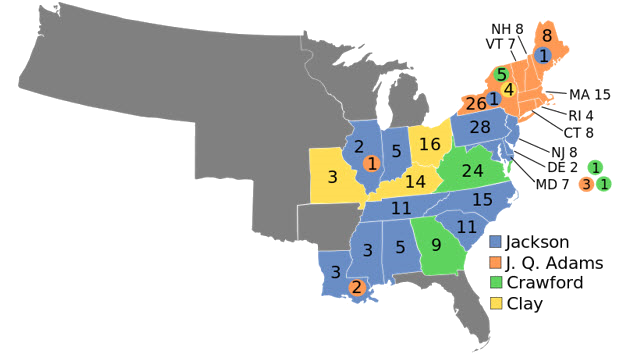

When

voters cast their ballots, Andrew Jackson received the largest number of

popular votes. However, he did not have

a majority of the electoral votes

required by the Constitution. Therefore,

the House of Representatives had to decide who would be the next

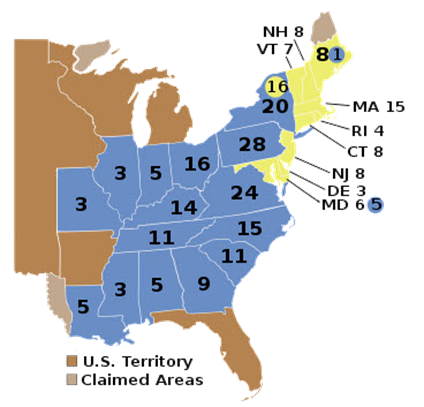

president. You can see the number of

electoral votes each candidates received on the map below. The gray areas represent parts of the country

that were territories but not yet states.

According to the Constitution, the three candidates with the most

electoral votes were to be presented to the House. They were Jackson, Adams and Crawford. Clay finished fourth and was out of the

presidential race. The remaining

candidates knew that Henry Clay still had the power to influence congressmen because

he was Speaker of the House of Representatives.

Distribution of the Electoral Votes: Presidential Election of 1824

Each

candidate sent a delegation to earn Henry Clay’s support. The Jackson people made a strong case. Old

Hickory, as he was nicknamed, had been the people’s choice and had received

the largest number of electoral votes.

William Crawford’s team had little to present since their candidate’s

health had not improved. John Quincy

Adams, on the other hand, remained a serious challenger. Adams won Clay’s backing because he supported

Clay’s American System. John Quincy

Adams was chosen as president by the House of Representatives on February 9,

1825.

Go to Questions 1 through 3.

Go to Questions 1 through 3.

Plotting

Revenge

Following

his inauguration, President Adams appointed his Cabinet and named Henry Clay as

secretary of state. Andrew Jackson,

furious over losing the election, was convinced that this confirmed a secret

deal between Adams and Clay. Although

there was no evidence to support this claim, Jackson went home to Tennessee and

began to plan a strategy to make it very difficult for the new administration

to accomplish anything. Take a quick

tour of the Hermitage, Andrew

Jackson’s home, by clicking on the graphic below.

With

the help of Senator Martin Van Buren

from New York, Jackson organized strong opposition in Congress against any

legislation proposed by President Adams.

This made John Quincy Adams appear to be a very weak president. At the same time, Jackson and his followers

organized a new political party, the Democratic

Party. With Jackson as their leader,

the Democrats appealed to those who were unhappy with Adams and the National Republicans, the new name for

members of the Republican Party. As the

election of 1828 approached, the National Republicans and the Democrats

prepared for a tough campaign.

Go to Questions 4 and 5.

Go to Questions 4 and 5.

The

Election of 1828

Most

Americans expected both parties to engage in plenty of mudslinging during the

presidential election campaign of 1828, and they were not disappointed. There were vicious attacks on the character

and background of each candidate. John Quincy Adams ran for a second term

as the National Republican nominee with Richard

Rush as the vice presidential contender.

The Democrats relied on state conventions or state legislatures rather

than caucuses to choose their candidates.

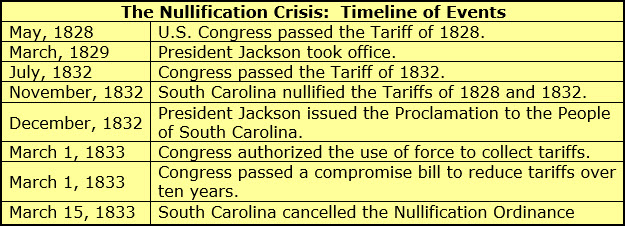

Andrew Jackson was the

Democratic choice for president, and John

C. Calhoun ran for vice president after joining the Democratic Party. When the votes were counted, Jackson won 56%

of the popular vote and a clear majority in the Electoral College as noted on

the map pictured below. John Quincy

Adam’s reaction was similar to that of his father when he lost the election of

1800. He left Washington D.C. shortly

after midnight on his last day in office and refused to attend the inauguration

of President Jackson.

Distribution of Electoral Votes: Presidential Election of 1828

Go to Questions 6 through 8.

Go to Questions 6 through 8.

Jackson’s

Presidential Style

Throughout

his presidential campaign, Andrew Jackson referred to himself as the champion

of the common man. He stressed his life

story, frontier experience and military career rather than political

issues. Because most states no longer

listed the ownership of property as a voting requirement, the number of white

males participating in presidential elections increased from 27% to 58% by 1828. This meant that many Americans, including

sharecroppers, factory workers and farm hands, voted for the first time in the

elections held during the 1820s. Many of

these people saw as Andrew Jackson their president. Westerners, in particular, were overjoyed when

Jackson won the presidency. For the

first time, Americans had chosen a chief executive who was not from Virginia or

Massachusetts. Settlers in the West saw

Jackson as someone who cared about them and understood their problems.

On

March 4, 1829, President-elect Andrew Jackson made his way on foot down

Pennsylvania Avenue to his inaugural ceremony at the U.S. Capitol. Thousands of people lined the route to cheer

his accomplishment. After one of the

shortest inaugural addresses in United States’ history, Jackson made his way to

the White House. Following a custom

started by Thomas Jefferson, Jackson’s followers had planned to hold an open

house for his supporters. An

enthusiastic crowd of common people, who had come to shake hands with their

president, circled the White House.

Because there were no guards to provide security, they made their way

indoors. The throng around Andrew

Jackson was so great that his friends had to protect him from injury. Socialite Mary Smith was a frequent guest at

White House social functions. Read her

description of the event quoted in the graphic below.

Once

Jackson took office, he was determined to reward the people who helped him win

the election. He planned to accomplish

this by hiring them as federal workers. To

create these positions, Jackson fired 20% of those who were employed by the

national government. Then, the President

replaced them with loyal friends, members of the Democratic Party and financial

contributors to his campaign. Jackson

insisted that it was more democratic to change people in government service

periodically. Although his opponents

argued that it was unfair not to choose the person best qualified for the job,

the President’s system remained in effect.

The policy of rewarding loyal political supporters with government jobs

became known as the spoils system. The term was derived from the following

phrase used by Senator William L. Marcy to describe Jackson’s policy: To the victors (winners) belong the spoils

(rewards)! The spoils system continued

to be a source of controversy long after Jackson left office. This cartoon picturing Jackson on a pig, a

symbol of greed, is an example of the strong opinions generated by the practice.

Figure 1Cartoon

Critical of Jackson and the Spoils System:

Thomas Nast

Like

previous presidents, Andrew Jackson appointed members to his Cabinet. Unlike his predecessors, he did not usually

rely on or meet with them. When he

needed advice, Jackson talked things over with trusted friends and business

associates. They often sat around a table in the White House kitchen during

their discussions. Jackson’s critics

called the group the Kitchen Cabinet

and complained about its influence on presidential decisions. Andrew Jackson’s strong will and commanding

presence, however, left little doubt as to who was in charge of the executive

branch. During his eight years in

office, President Jackson made his share of enemies but remained popular by

appealing directly to the people for support.

He also vetoed more bills passed by Congress than all the other previous

presidents put together.

![]() Go to Questions 9 through 14.

Go to Questions 9 through 14.

The

Tariff of Abominations

The

Early

in Jackson’s presidency, a major disagreement developed between the sections of

the country concerning tariffs. At

first, tariffs generated money to run the government and to pay the national

debt. After 1816, Congress passed

several protective tariffs to help

American industries. The taxes usually

made imported products more expensive than those manufactured in the United

States. This helped American industry to

grow and to be competitive. Because most

factories were located in the North, that section of the country strongly

supported this policy. Southerners,

however, questioned its benefits to the country as a whole.

In

1828, the controversy over tariffs intensified.

Congress passed and President John Quincy Adams signed a new protective

tariff law that increased taxes on imported goods to a new high. Manufacturers in the northeast were happy

with the legislation, but it angered planters throughout the South. They argued that it forced all Americans to

pay higher prices. Southerners also

feared that European nations would retaliate with tariffs of their own on

cotton. Decreased sales of cotton abroad

meant less money for plantation owners.

To emphasize just how much they hated this law, people throughout the

South referred to it as the Tariff of

Abominations. In South Carolina,

there was talk of leaving the Union.

Go to Questions 15 and 16.

Go to Questions 15 and 16.

The

Nullification Crisis

South

Carolina planters were determined to fight the tariff, and they turned to the

state’s most powerful politician, Vice President John C. Calhoun, for help.

This placed Calhoun in a difficult position. He knew that Andrew Jackson would enforce the

tariff because it was a federal law. At

the same time, he did not want to lose the support of South Carolinians. Therefore, Calhoun tried to find a way for

South Carolina to avoid obeying the law.

Vice

President Calhoun argued that a state or a group of states had the right to

cancel, or to nullify, a federal law

if it was in the state’s best interest.

He reasoned that the Union existed because the states had voluntarily

agreed to give up some of their authority.

If a law passed by Congress gave the national government powers not

specifically mentioned in the Constitution, a state could legally nullify

it. In other words, the law did not have

to be obeyed within that state. To deny

this right to the states was dangerous, Calhoun noted, because, without it, the

federal government could easily abuse its authority. This made perfect sense to southerners, who

viewed the Tariff of 1828 as a law that deserved to be nullified.

Calhoun’s

theory of nullification caused heated debates in Congress over states’

rights. One of the most famous exchanges

took place in the United States Senate in January of 1830. Robert

Hayne, a young senator from South Carolina, defended the right of a state

to nullify a federal law and concluded that a state also had the right to

leave, or to secede, from the

Union. Daniel Webster, representing Massachusetts in the Senate, responded

by delivering a dramatic speech that emphasize the importance of the Union and

the Constitution. Southerners hoped that

President Jackson would side with them, but Jackson made it clear that, during

his presidency, the Union would be preserved.

Vice President Calhoun knew that Jackson would not change his mind. After resigning as vice president, Calhoun was

elected to represent South Carolina as a U.S. Senator.

An Artist's Rendition

of Daniel Webster during the Debate

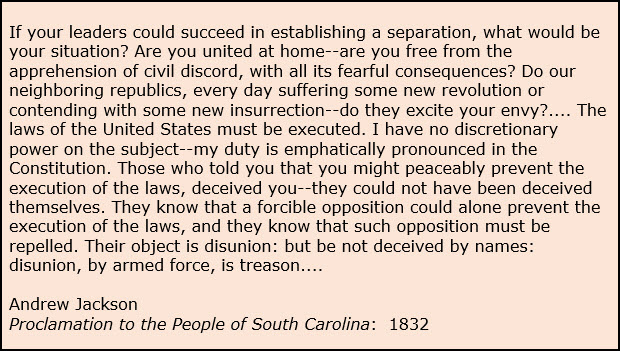

Anger

over the tariff continued to escalate throughout the South. In July of 1832, Congress passed a new, lower

tariff law, but it did little to improve the situation. South Carolina passed the Order of Nullification, which declared

that the Tariff of 1828 and the Tariff of 1832 would not be observed in the

state. Some South Carolinians suggested

that the state should leave the Union. This

resulted in a stern response from President Jackson, who was determined to

enforce the federal law as he was sworn to do.

First, he alerted the army to prepare 50,000 soldiers to enforce the

tariff laws in South Carolina. Then, he

issued the Proclamation to the People of

South Carolina. As you can see from

reading the excerpt below, Andrew Jackson made it very clear that South

Carolinians would pay a high price if they chose to ignore federal law.

Although

the proclamation was issued, President Jackson worked behind the scenes to

resolve the crisis. He met with the

congressional leaders of the Democratic Party and asked them to help write a

tariff bill that would be acceptable to southerners. With the assistance of Henry Clay and his ability to encourage compromise, Congress passed

a new tariff law in 1833. It gradually

lowered taxes on imports for the next ten years. Jackson wanted to make sure that South

Carolina would accept Clay’s compromise.

For this reason, he convinced Congress to pass the Force Act, which permitted the president to use the United States

military to enforce laws established by Congress. On March 15, 1833, South Carolina removed the

Nullification Ordinance. In the long

term, however, this did not end southern interest in succession or narrow the

gap between the North and the South. Radicals

in South Carolina realized that they would need the support of other states if

they were going to challenge the federal government. They also learned that the federal government

would not permit states to leave the Union without a fight.

![]() Go to Questions 17 through 25.

Go to Questions 17 through 25.

What

Happened Next?

The

Nullification Crisis was only one of the controversies that erupted during the

Jackson administration. As the United

States expanded westward, settlers on the frontier demanded that Native

Americans be relocated. President

Jackson, a frontiersman himself, supported their position. This led to the Indian Removal Act and Native

American resistance. Jackson also became

involved in another political battle when he vetoed the bill to renew the

Second Bank of the United States. In the

next unit, you will see how these issues affected Jackson’s presidency and

power of the executive branch. Before

moving on, review the names and terms in Unit 23; then, complete Questions 26

through 35.

Go to Questions 26 through 35.

Go to Questions 26 through 35.

|

| Unit 24 Presidential Profile: John Quincy Adams Article and Quiz |

| Unit 24 Presidential Profile: John Quincy Adams Writing Exercise |

| Unit 24 What's the Big Idea? Worksheet |