THINKING LIKE A

HISTORIAN:

THINKING LIKE A

HISTORIAN:

† PATRIOTS AND

LOYALISTS

†

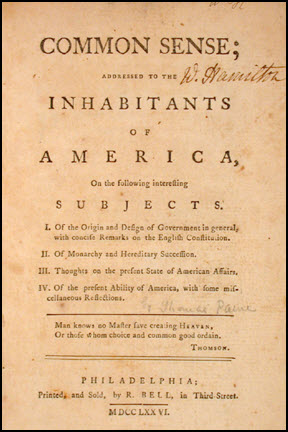

Common Sense by

Thomas Paine:† A Pamphlet from the

Colonial Era

†

Unit

Overview

Americans

sometimes regard their colonial past as a time in which all colonists agreed on

the subject of independence.† In reality,

not everyone thought that a separation from Great Britain was a good idea.† Historians work to correct these types of

false impressions through the careful study of primary and secondary

sources.† The activities in this unit

will help you see how this is accomplished.†

Letís get started.

Primary

and Secondary Sources

When

studying history, it is not unusual to encounter conflicting pieces of

information.† Various eyewitnesses, for

example, may describe a particular event differently.† Some accounts may include details not

mentioned in others or may portray certain occurrences in an opposite

order.† It is the job of a historian to

sift through the material, to analyze the evidence and to separate factual information

from opinion or fiction.† Then, the

findings are used to construct arguments that support a particular

interpretation of the facts.† To do this

work, historians rely on primary and secondary sources.

Image Courtesy of

Mount Vernon Ladies' Association

Primary sources provide

first-hand information about historical events and help researchers to learn

what actually happened in a previous era.†

They are based on eye-witness accounts of individuals who lived during

the time period in question.† Diaries,

letters, speeches, legal documents, written laws, newspaper editorials and

journals are all examples of primary sources that have given us valuable

glimpses of life in the past.†

Photographs, audio recordings, literature, cartoons, music and paintings

also have been used to give accurate descriptions of earlier times.† With new developments in technology,

historians analyzing the current century will regard email messages, cell phone

records and posts on social media as primary sources.† Secondary

sources, on the other hand, explain the past by interpreting primary

sources and are written by people who were not present at the events they

discuss.† Examples of secondary sources

include textbooks, encyclopedias, articles from magazines, and television

documentaries.

† Go to Questions 1 through 4.

† Go to Questions 1 through 4.

Bias

and Primary Sources

Historians

view sources with a critical eye and carefully analyze the information that

they present.† This is especially true of

primary sources.† While they describe the

society and the times in which they were written, these resources reflect the

writerís or creatorís point of view and sometimes slant or ignore certain

facts.† Therefore, it is always important

to take into account when, by whom and for what purpose a primary source was

originally intended.† †

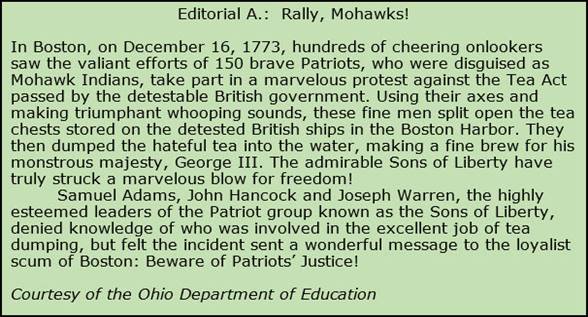

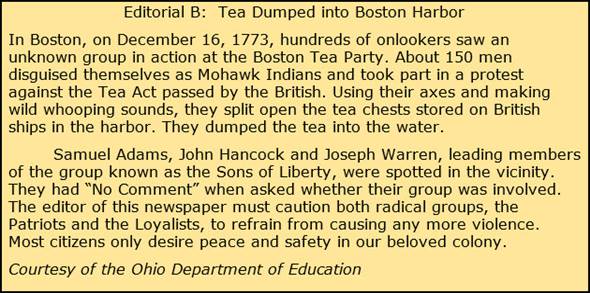

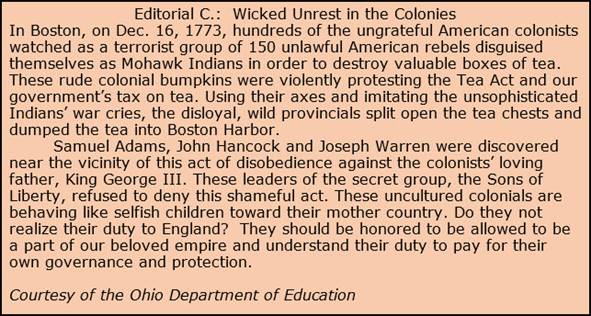

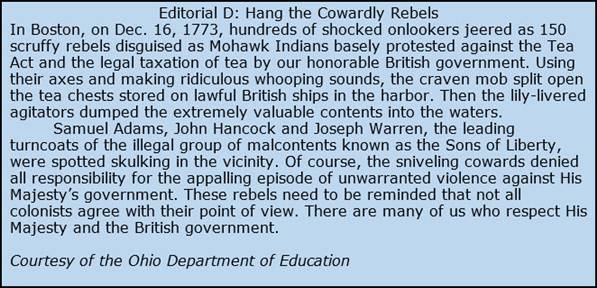

Letís

look at an example.† Four fictional

newspapers from the colonial era are listed below.† Read each description carefully.

∑

The London Daily

Chronicle:† Published in London, England, the Chronicleís staff agrees with the British government.† Its editor has invested in the British East

India Company and believes that saving the business is in the best interest of

the empire.† In his opinion, the

colonists are behaving rebelliously and must be taught a lesson.

∑

The Liberty News:† A member of the Sons of Liberty owns this paper

which is published in Boston.† The editor

favors independence from Great Britain.

∑

The Colonial

Examiner:† The Examiner

is also published in Boston.† The editor

prides himself on balanced and accurate reporting.† He is trying to remain neutral on the subject

of independence.

∑

The Loyal Gazette:† Some colonists, known as Loyalists, did not

consider the taxes imposed by the British to be unfair or to be good reasons to

rebel.† The editor of the Gazette agrees with this

philosophy.† Published in Charles Town

across the harbor from Boston, the paperís editorials frequently reflect his

views.†

Read

the four fictional editorials pictured in the graphics below.† Each one presents a different view of the

Boston Tea Party.

††Go to

Questions 5 through 16. ††††

††Go to

Questions 5 through 16. ††††

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

††

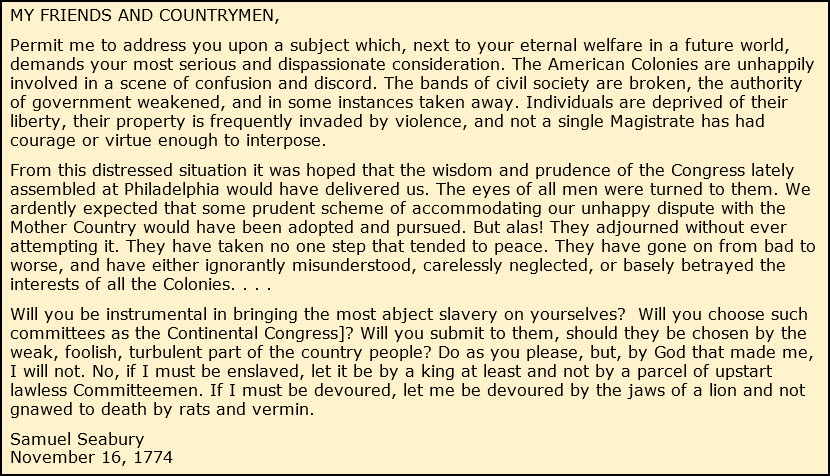

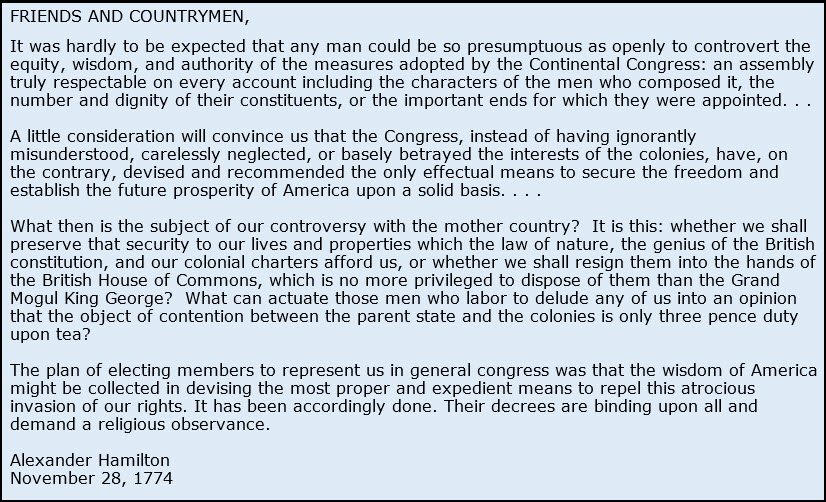

Loyalists and Patriots

Great Britain responded to the Boston Tea Party by issuing

the Coercive or Intolerable Acts, pieces of legislation that led to further

unrest in the colonies.† Some radical

colonists, who were called patriots,

began to consider the idea of separating from Britain, while the loyalists believed that a compromise

with their home country was a better option.†

The First Continental Congress included participants from both groups,

and delegates from each side reacted after the meeting adjourned.† Along with editorials in newspapers,

colonials often published essays on topics of interest in pamphlets, one or more pages that could be cheaply printed and

distributed.† Patriots and loyalists

exchanged opinions on specific topics in what became known as the pamphlet wars.† Samuel Seabury, a loyalist, made his thoughts

on the First Continental Congress public in this manner and drew a response

from Alexander Hamilton, a well-known patriot.†

Read their comments as quoted in the graphics below.

Both

pamphlets, which were printed by James Livingston in New York, were read

throughout the colonies.† In 1775,

members of the Connecticut branch of the Sons of Liberty were so offended by

Seaburyís comments that they traveled to New York, broke into Livingstonís shop

and destroyed his press.†

† Go to Questions 17 through 25. †

† Go to Questions 17 through 25. †

What

Happened Next?

In

the spring of 1775, the Second Continental Congress assembled in

Philadelphia.† The delegates included

what were to become some of Americaís best-known political figures.† Their decisions, such as the formation of a

Continental Army and a formal declaration of independence, would have a

profound impact on both North American and world history. In the next unit, you

will see just how the big break up became official.†

Additional Activities and Resources

Unit 9 Identifying Primary and Secondary Sources Worksheet