The Southern

Colonies

The Southern

Colonies

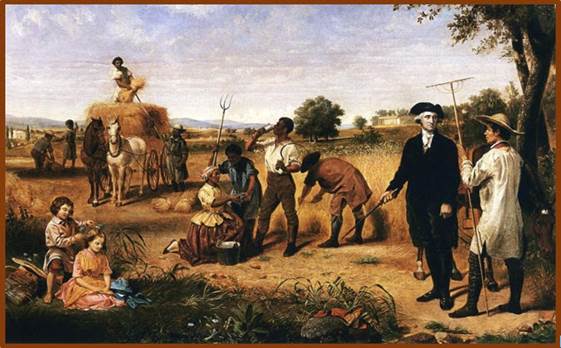

Artist's

Rendition of George Washington's Plantation:

Painted by Junius Brutus Sterns, 1851

Unit

Overview

Since

the founding of Jamestown in 1607, the English continued to establish colonies

along the southeastern shore of the North American continent. The Southern Colonies, which included

Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, attracted both

proprietors and settlers. A long growing

season and rich soil encouraged the growth of cash crops and provided

opportunities for large profits.

However, rice, indigo and tobacco were labor-intensive and required

large numbers of workers. As prices on

the world market became more competitive, indentured servants and African slaves

were used to work large tracts of land known as plantations. Was profit the only reason behind the

founding of the Southern Colonies? Why

did the use of African slaves increase so dramatically, and how did slavery

become a race-based institution? Let’s

see how it all happened.

Filling

the Labor Gap

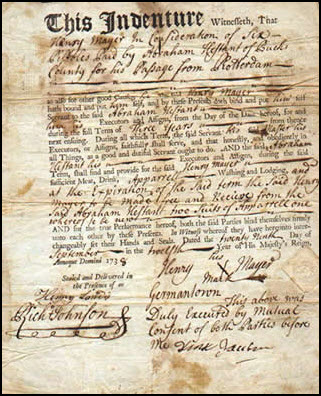

As

the English soon discovered, the establishment of colonies demanded a large

amount of physical labor. Clearing land,

constructing houses, planting crops and tilling fields intensified the need for

workers. To fill the gap, many people

came to North America as indentured

servants. To pay for their passage,

these individuals signed contracts to work without pay for a specified number of

years. Although agreements varied, a

seven-year term of service was the most common.

When they completed their obligation, indentured servants were freed and

given a small piece of property.

Original Contract for an Indentured

Servant

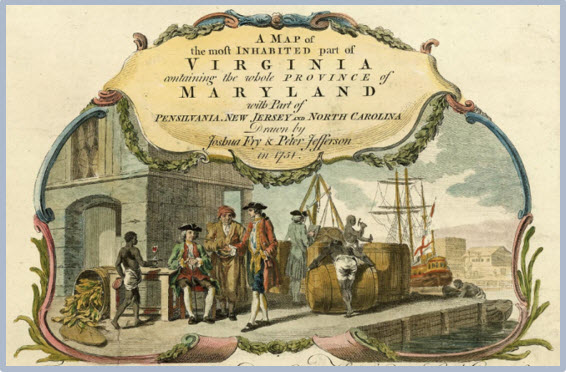

African

slaves, brought to the colonies against their will, also provided the labor

necessary to build the English colonies.

In 1619, a Dutch trader arrived in Jamestown and sold twenty Africans to

the English settlers. Slavery has long

been associated with the American South, but it existed in the New England and

Middle Colonies during the colonial period.

Although their overall numbers were small in these areas, the cities

held the largest concentrations of blacks.

For example, 20% of Boston’s population was made up of Africans by 1750. In northern urban areas, the enslaved served

as household servants, craftsmen and dock workers.

Illustration from the

Jefferson/Fry Map of Virginia: Courtesy

of the University of Virginia Archives

In

the Southern Colonies, slaves primarily were purchased for agricultural work. Some of the first Africans in Virginia were

treated as indentured servants and became freemen. They purchased land, owned indentured

servants and raised families. When

tobacco prices on the world market fell in the 1660s, opportunities for blacks

in the Southern Colonies quickly diminished. When profits decreased, English

planters relied more and more on slaves to maintain their earnings. Virginians passed laws in their colonial

legislature to deny gun ownership to Africans and to strip them of their legal

rights. Other southern colonies that

depended on labor-intensive crops passed similar measures. As a result, Africans were marked as

inferior, and racially based slavery became a permanent condition for those who

continued to arrive involuntarily.

Go to Questions 1 through 5.

Go to Questions 1 through 5.

Founding

Maryland

Sir George Calvert, titled Lord Baltimore, asked King Charles I to

grant him a charter for a tract of land in the New World. He hoped to achieve two goals by acquiring

this property. Calvert planned to create

a safe home for Roman Catholics, who were persecuted in England, and to

increase the family fortune. When the

king issued the document in 1632, the elder Calvert had died so his son Cecil

inherited the project. As the

proprietor, he had the right to appoint a governor, give land to others, coin

money and make laws. Rather than go to North America himself, the new Lord

Baltimore sent his two brothers to establish a settlement. They arrived in 1634 accompanied by 200

settlers. The colony, located between Pennsylvania and Virginia, was named Maryland. To learn more about its founding, watch the

video listed below.

![]() Maryland: The Proprietary

Colonies

Maryland: The Proprietary

Colonies

Since

Virginia had realized profits from the sale of tobacco, the Maryland colonists

planted it but wanted to avoid becoming too dependent on a single crop. Therefore, farmers who grew tobacco agreed to

set aside at least two acres for corn.

This encouraged the Marylanders to cultivate wheat, fruits, vegetables

and other staples to feed their families.

The town of Baltimore, founded

in 1729, provided a good seaport and became the colony’s largest

settlement. In the meantime, the

Calverts gave large estates to their relatives and friends. As the number of plantations grew, the need

for workers increased. Choosing not to

recruit farmhands and not to offer wages, landowners purchased enslaved

Africans and the contracts of indentured servants to provide the necessary

labor.

Baltimore in 1752:

Edward J. Coale, 1817

The Calvert

family continued to face challenges as the colony grew. The colonists soon demanded some say in their

government, and Lord Baltimore permitted the election of an assembly to make

laws. Because the colony was originally

intended to be a haven for Catholics, the arrival of large numbers of

Protestants was a concern. In an effort

to protect Catholics from religious persecution by the Protestant majority,

Lord Baltimore convinced the legislative assembly to pass the Act of Religious Toleration which permitted

religious freedom throughout the colony.

There were also border disputes between Pennsylvania and Maryland. To resolve these issues, Charles Mason and Jerimiah

Dixon, two European scientists, were hired to survey the dividing line

between the two colonies. They marked

the border, known as the Mason-Dixon

Line, with stones displaying the Calvert family crest on one side and the

Penn crest on the other.

Go to Questions 6 through 10.

Go to Questions 6 through 10.

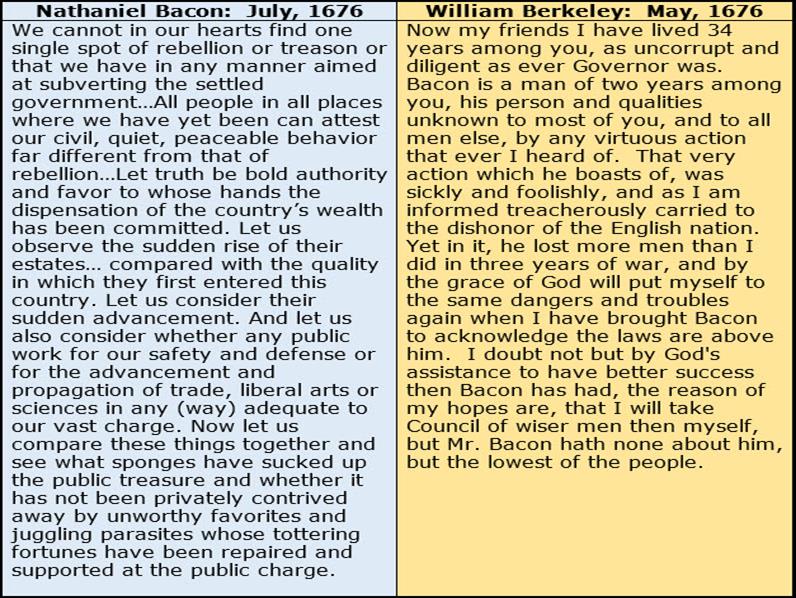

Virginia

and Bacon’s Rebellion

As

other colonies were founded, Virginia continued to grow. Because wealthy tobacco planters occupied the

best land near the coast, new settlers moved inland and pushed westward. By the 1640s, they had come into conflict

with the Native Americans who inhabited the same region. William

Berkeley, Virginia’s governor, hoped to avoid a confrontation like King

Philip’s War by negotiating an agreement with the Indians. In exchange for extending the colony’s land

in the west, Berkeley pledged to keep the settlers from advancing any further

into Indian holdings. The westerners, led by Nathaniel Bacon, opposed this arrangement because they wanted to

clear more land for their farms. They

also believed that the governor was simply trying to preserve the colony’s

valuable fur-trading business with the Indians.

Bacon and Berkeley defended their positions with public statements like

the ones quoted below.

In

1676, Bacon and his supporters attacked Native American villages and tried to

take more land from the Indians by force.

Determined to crush the rebellion, Governor Berkeley organized his own

army, but Bacon’s forces marched on Jamestown, set fire to the town and drove

out the governor. Before he could take

charge of Virginia’s government, Nathaniel Bacon contracted an illness and

died. This ended the rebellion, but the

event had some significant consequences.

Virginia’s colonists had discovered that a group of unified citizens

could be a powerful force, and the Indians had learned that guarantees concerning

their land meant little to the European settlers.

Go to Questions 11 through18.

Go to Questions 11 through18.

The

Carolinas

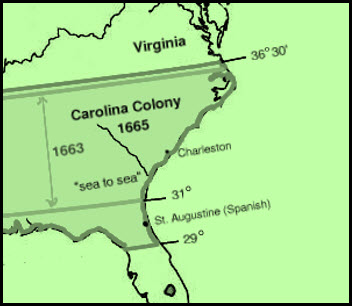

As a

reward for their support, King Charles II offered eight of his friends a

proprietary colony south of Virginia in 1663 and named the territory Carolina based on the Latin word for

Charles. The eight proprietors reserved

large estates for themselves and planned to make a profit by selling or renting

the remainder. Colonists began to arrive

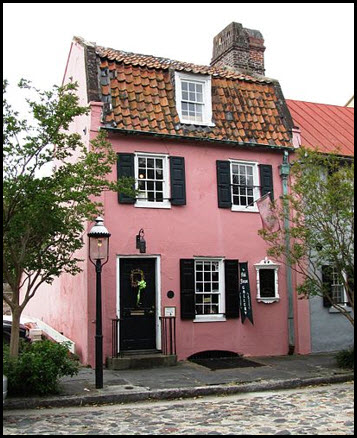

in 1670, and they built Charles Town or, as it was eventually called, Charleston. Charleston grew into the fourth largest city

on the eastern seaboard. Because the

colony was large, climate and geography differed from north to south. The northern section of Carolina with its

large forests and less humid climate attracted farmers who grew tobacco and cut

trees for lumber. Because there were no

adequate harbors along the northern coast of the colony, settlers relied on

Virginia’s ports and merchants to conduct their trade.

The Pink House, Charleston's Oldest

Building: Photo by Brian

Stansberry/Creative Commons

The

southern half of the colony was blessed with rich soil and an excellent harbor

at Charles Town. Many of the settlers in

this region came from Barbados and

other English colonies in the Caribbean.

They brought their slaves with them. By 1680, planters discovered that rice grew well in the warm, humid

coastal lowlands, and it soon became the colony’s leading crop. In the 1740s,

another valuable plant would provide additional profits. Learn more about South Carolina’s developing

plantation economy by viewing the video listed below.

Colonel George Lucas, a British

officer stationed in the West Indies on the island of Antiqua, moved his family

to a plantation in the Carolinas. After

he returned to duty, his daughter Eliza

Lucas Pinckney looked for ways to keep the plantation out of debt. She experimented with seeds of the indigo plant that her father had sent

from the West Indies. When properly

cultivated and processed, indigo yielded a rich, blue dye popular for coloring

cloth in Europe. Eliza not only made

money for herself with the indigo trade, but she also shared seeds with her

neighbors. This created another valuable

cash crop for the Carolinas.

Map Showing the Carolina Colony

Like

rice, the growth of indigo was labor-intensive so the demand for slaves

increased. By the early 1700s, more than

half of the people living in southern Carolina were enslaved Africans. At the same time, the colonists grew

increasingly dissatisfied with the proprietors, and they demanded a greater

role in the colony’s government. By

1729, Carolina had become the two royal colonies of North Carolina and South

Carolina.

Go to Questions 19

through 21.

Go to Questions 19

through 21.

Oglethorpe’s

Experiment

Georgia, the last of Britain’s colonies in

North America, was established in 1733. James Oglethorpe and nineteen other

proprietors received a charter to create a settlement where poor people and

those who were deeply in debt could make a new life for themselves. For the British government, Oglethorpe’s idea

served a second purpose. Because Spain

and England were at war in the early 1700s, England feared an attack launched

from Spain’s forts in Florida. Since

Georgia, as the new colony was named, was located below South Carolina, it

could act as a buffer to help protect the English from the Spanish.

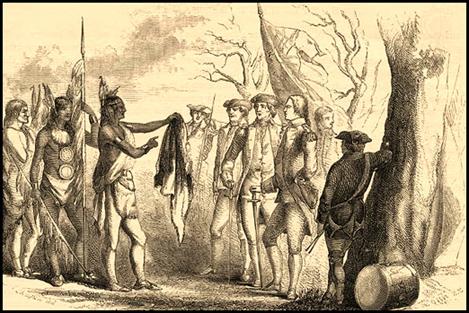

Oglethorpe Meeting with Chief Yamacraw of the

Tomochichi Tribe

In

1733, Oglethorpe and his first group of settlers that had been handpicked by

the proprietors arrived in North America. Some of their first projects included

the construction of a series of forts to defend themselves from the Spanish and

the establishment of the town of Savannah. In

terms of daily life, Oglethorpe had a very specific vision for the colony. Thinking that small farms would encourage the

settlers to do their own work, he gave each one only fifty acres of land, tools

and seeds. Because he wanted his colonists to be independent, hardworking and

Protestant, strict rules outlawed slavery, rum and Catholicism. The video listed below describes Oglethorpe’s

laws and their impact.

Even

though Georgia’s farms successfully produced rice, indigo, corn, wheat and

livestock, the colony’s growth was disappointingly slow. Only a few debtors took advantage of

Oglethorpe’s offer, but hundreds of poor people did migrate to Georgia. They came from Great Britain, Germany,

Switzerland and other European nations.

In a few years, Georgia’s population had the largest percentage of

non-British residents within the thirteen colonies. Although they came from diverse backgrounds,

the colonists agreed that Oglethorpe’s laws were too restrictive and too numerous. He finally permitted the settlers have larger

farms and lifted the ban on slavery. For

the colonists, however, this was simply too little too late. Frustrated and disappointed, the proprietors

turned the colony over to the king and returned to England.

Go to Questions 22 through 24.

Go to Questions 22 through 24.

What

Happened Next?

Over

a span of one hundred and twenty-five years, England had lined the eastern

coast of North America with thirteen colonies.

By 1750, they were generally prosperous, well populated and less

dependent on their home country for survival.

Englishmen on both sides of the Atlantic were proud of this

accomplishment. Because distance and

troubles with other European powers presented challenges to ruling an empire

across the sea, England granted the colonists a significant amount of freedom

over their local affairs. However, the

English firmly believed that the colonies existed to benefit their economy, and

attempts to control colonial trade for their own profit angered the

colonists. Before taking a closer look

at the deepening rift between England and colonies, review the names and terms

found in Unit 5; then, answer Questions 25 through 32.

Go to Questions 25 through 32.

Go to Questions 25 through 32.

|

| Unit 5 Settlers, Slaves, and Servants |

| Unit 5 The Thirteen Colonies |

| Unit 5 What's the Big Idea? Worksheet |