COLD

WAR POLICY AND THE VIETNAM WAR

American Forces

in the Mekong Delta:† 1967

Unit Overview

As the Cold War extended to Southeast Asia, Vietnam became a foreign policy dilemma for Presidents Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy; for Lyndon Johnson, it was a political disaster.† The Vietnam War was costly, long and controversial.† As Americans witnessed the carnage of war on the evening news, many began to question the purpose and the necessity of the U.S. involvement.† Antiwar sentiment grew, the conflict escalated and the military achieved only limited success.† Was America obligated to prevent the communist takeover of South Vietnam?† Was the Vietnam War a blunder or a necessity?† How did American public opinion affect the conduct of the war?† Form your own answers to these and other questions as we study the Vietnam War.

The Demise of

French Indochina

†

By

the late nineteenth century, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam had become colonial

possessions of France and were referred to collectively as French

Indochina.† Governors, who were appointed

by the French government, concentrated on increasing profits, and the native

people worked for the benefit of their French overlords rather than

themselves.† Eventually, this led the

nations of French Indochina to pursue independence.† In Vietnam, the League for the Independence of Vietnam, generally known as the Viet Minh, was organized as a political

party in 1941; its aim was to free the country from colonial rule. †Less than a month after the Japanese

surrendered in World War II, Ho Chi Minh,

leader of the Viet Minh, formally declared Vietnam's independence. The Viet Minh

had a strong base of popular support in northern Vietnam and became an openly

communist organization in the mid-1950s.

The

French refused to relinquish their control of Indochina and denied the

recognition of Vietnam as a free state unless it remained in the French Union.

Fighting between the French and the Viet Minh broke out in 1946 and continued

until the French lost the Battle of Dien

Bien Phu in 1954.† When an

international conference in Geneva

negotiated a cease-fire, the Vietnamese that had fought under French command

moved south of the 17th parallel,

and the Viet Minh went north of the 17th parallel.† This established a military demarcation line

surrounded by a demilitarized zone (DMZ). Based on this decision, thousands of

people abandoned their homes to move north or south, and the French began their

final departure from Vietnam. The agreement left the communist-led Viet Minh in

control of the northern half of

![]() † The Siege of Dien Bien Phu: A French Military

Disaster

† The Siege of Dien Bien Phu: A French Military

Disaster

Go

to Questions 1 through 4.

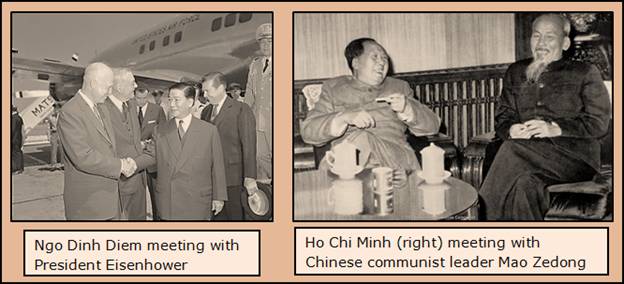

The Diem Regime

The

agreement reached in Geneva in 1954 also stipulated that free elections were to

be held throughout Vietnam in 1956 under the supervision of an International

Control Committee.† The goal was to unify

North and South Vietnam under a single government chosen by popular

election.† North Vietnam expected to win

this election thanks to the broad political organization that it had built up

in both parts of Vietnam. Diem, who had solidified his control over South

Vietnam, refused to hold the scheduled elections. The United States, following

its policy of containment, supported his position. In response, the North

Vietnamese decided to merge the two Vietnams through military force rather than

by political means.

ARVM Soldiers

with an American Advisor

U.S.

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles,

fearing the spread of communism in Asia, persuaded the U.S. government to

provide economic and military assistance to the Diem regime.† However, the prime minister became

increasingly unpopular with the people of South Vietnam. Diem replaced the

traditionally elected village councils with Saigon-appointed administrators and

aroused the anger of the Buddhists by selecting Roman Catholics for top

government positions. Guerrilla warfare spread as the Viet Cong, Viet Minh soldiers who were trained and armed in the

North, raided South Vietnam. The Diem government requested and received more

American military advisers and equipment to build up the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), but it could not halt the

growing presence of communist forces. U.S. President John F. Kennedy sent more non-combat military personnel after the

South Vietnamese communist insurgents formed an organization called the National Liberation Front (NLF) in

December of 1960. By the end of 1962, the number of U.S. military advisers in

South Vietnam had increased from 900 to 11,000, and Kennedy authorized them to

fight if they were fired upon.

Go

to Questions 5 through 9.

The Gulf of Tonkin

Resolution

Popular

dissatisfaction with Diem continued to grow, even within his army, and Diem was

assassinated during a military coup on November 1, 1963. A series of unstable

administrations followed in quick succession, and the lack of political

stability encouraged the Viet Cong to increase their activities while the South

Vietnam.† On August.2, 1964, North

Vietnamese patrol boats fired on the U.S. destroyer Maddox in the Gulf of Tonkin.†

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution,

endorsed almost unanimously by the U.S. Congress, gave the president the formal

authority for full-scale American intervention in the Vietnam War.† Lyndon

Johnson used this power to order the bombing of North Vietnam by U.S. naval

planes.† After 1965, U.S. involvement

escalated rapidly in response to the growing strength of the Viet Cong and to

the inability of the ARVN to suppress the Viet Cong on its own.† The determination to maintain the

independence of South Vietnam and to preserve American credibility continued to

draw the United States more deeply into the conflict.† Support for the domino theory, the concept that one nation succumbing to communism

in a region of the world would be quickly followed by others, encouraged the

Johnson administrationís stance on Vietnam.

![]() † Responding to Threat: President Johnson Speaks to

the American People

† Responding to Threat: President Johnson Speaks to

the American People

On

the night of February 7, 1965, the Viet Cong attacked the U.S. base at Pleiku,

killing eight soldiers and wounding 126 more. Johnson ordered a reprisal of the

bombing of North Vietnam. Three days later, the Viet Cong raided another U.S.

military installation at Qui Nhon, and this time, Johnson ordered aerial

attacks against Hanoi, the capital

of North Vietnam.† On March 6, two

battalions of Marines landed on the beaches near Da Nang to relieve that

embattled city. By June of 1965, 50,000 U.S. troops had arrived to assist the

ARVN, but small contingents of the North Vietnamese army joined the Viet Cong

in South Vietnam, which they reached by following the Ho Chi Minh Trail west of the Cambodian border.† President Johnson authorized the bombardment

of this supply line, but it extended the war into both Laos and Cambodia.

U.S. Marines

destroying bunkers and tunnels used by the Viet Cong

The

government in

Go

to Questions 10 through 14.

The Tet Offensive

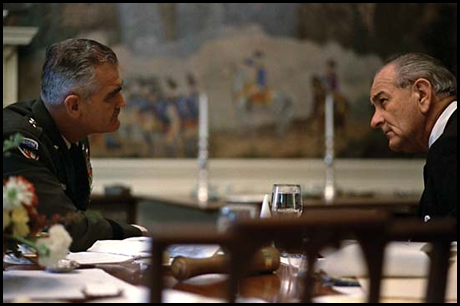

President Johnson meeting with General Westmoreland

Go

to Questions 15 through 17.

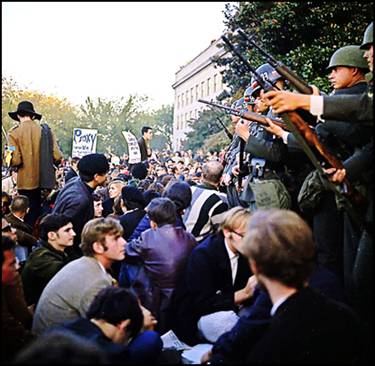

The Impact of

Public Opinion

Although

the general uprising that the NLF expected had not materialized, the offensive

brought about an important strategic effect.†

It convinced a number of Americans that, contrary to their government's

claims, the insurgency in South Vietnam could not be crushed and the war would

continue for years to come. In

the

General

Westmoreland requested more troops to widen the war after the Tet Offensive,

but the shifting balance of American public opinion now favored a de-escalation

of the conflict. On March 31, 1968, President Johnson announced in a television

address that bombing north of the 20th parallel would cease and that he would

not seek reelection to the presidency in the fall. The communist leadership in Hanoi

responded to the reduction in bombing by curtailing its military efforts; In October,

Johnson ordered a total bombing halt. During the interim, the

Vietnam War Protest at the Pentagon:† 1967

Go

to Questions 18 through 20.

Whatís Next?††

The

escalation of the Vietnam War and its seemingly endless peace process continued

to divide Americans as the antiwar movement rapidly spread.† This spirit of rebellion went beyond the war

and inspired the counterculture, which defied tradition and conventional

thought.† In the next unit, you will

explore the effects of these changes.†

Review the terms and names found in this unit; then, answer Questions 21

through 30.

Go

to Questions 21 through 30.

|

| Unit 25 Main Points Worksheet |

| Unit 25 Writing Exercises: The Vietnam War |

| Unit 25 The Choice: President Johnson's Decision to go to War in Vietnam Article and Quiz |