THE

BILL OF RIGHTS: PART I

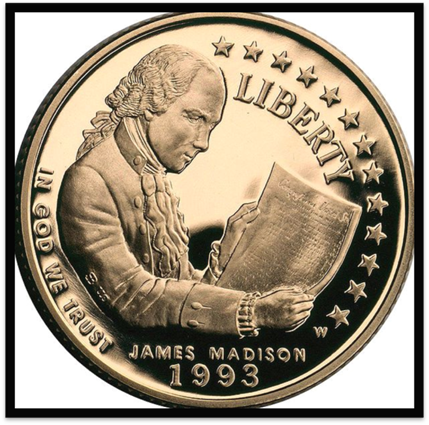

James Madison and the Bill of

Rights: Commemorative Coin

Unit Overview

As the U.S. Constitution was being debated and

ratified, the Anti-federalists argued for stronger protection of individual

rights and specific limits on the national government’s authority. The Constitution soon included ten

amendments, known as the Bill of Rights, to address these concerns. Today, they, too, are part of a living

document which continues to be defined and interpreted by judicial decisions,

legislation and other practices.

Americans still analyze and evaluate the freedoms of speech, religion,

press, assembly and petition on a daily basis.

However, these civil liberties are balanced by the obligation to respect

the rights of others.

![]()

The Constitution and the Rights of

Individuals

During the struggle for ratification of the

Constitution, Americans disagreed on a variety of political concepts and

principles, but the lack of a bill of rights caused the greatest

controversy. The Federalists, who

supported the adoption of the Constitution as it had been drafted by the

Constitutional Convention, insisted that most states had included detailed

bills of rights in their individual plans for government. They also argued that, in Article I: Section 9, the Constitution does ban certain

laws that violate the rights of individuals.

These include bills of attainder and ex post facto laws. Writs of habeas corpus can only be denied

under extreme circumstances.

Ø Bills of Attainder: A bill of attainder refers to an act of

Congress that singles out a group or individual and assigns a punishment

without a trial. Since the Founding

Fathers knew that legislation like this had been used by European rulers to

confiscate the property of prisoners, both Congress and state legislatures are

prohibited from passing this type of law.

Bills of attainder are rare in American history, but the Test Oath Act,

passed in 1865, is one example. The Test

Oath Act kept lawyers, who had been Confederate soldiers, from pleading cases

in federal courts. Since it singled out

a specific group and revoked privileges without a trial, the law was declared

unconstitutional in 1867.

Ø Ex Post Facto Laws: Ex post facto laws are also forbidden by the

Constitution. These laws, named from a

Latin phrase meaning “after the deed or the action,” are designed to punish

people for activities that were not illegal when they were performed. For example, if a state lowers the speed

limit on its highways, it cannot issue citations to those who were exceeding

that limit before the law was passed.

Ø Writs of Habeas Corpus: Section 9 of Article I also addresses writs

of habeas corpus. The term is derived

from a Latin phrase meaning “you have the body.” The body, in this instance, means collection

of evidence or valid reasons. When a

prisoner is held by the federal government, he/she can request a writ of habeas

corpus. Then, it is the government’s

obligation to bring the prisoner to court and to show that the arrest was made

for specific reasons. However, the

Constitution notes that these writs can be suspended if a case involves a

rebellion or an invasion that threatens public safety. President Lincoln chose this course of action

during the Civil War, and President George W. Bush also denied these writs

during the Global War on Terror. In both

situations, these presidential decisions aroused criticism and controversy.

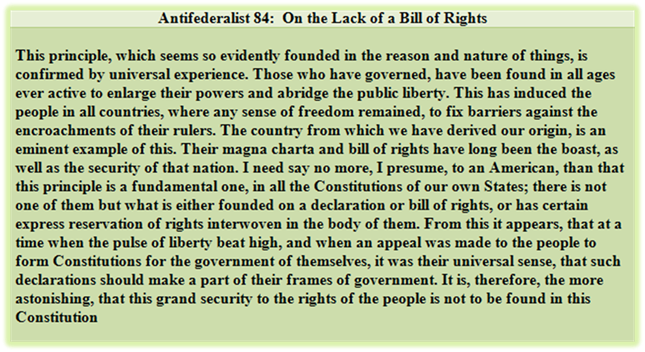

On the other hand, many Anti-federalists did not

believe that these safeguards were sufficient.

They saw the lack of a bill of rights as a critical flaw and refused to

support the adoption of the Constitution.

The debate over these issues became so intense that

several noted Federalists, such as George Washington and James Madison, agreed

to support the addition of a bill of rights once the Constitution was ratified.

Shortly after the Constitution was adopted, Congress sent proposals for twelve

amendments to the states. Ten, now known

as the Bill of Rights, were approved and were added to the Constitution in

1791. Originally, the purpose of the

first ten amendments was to protect the rights of citizens living under a

strong, national government. However,

throughout American history, the Bill of Rights has also been used to define

the principle of limited government and to ensure that state governments do not

violate basic civil rights.

![]() Go to Questions 1-5.

Go to Questions 1-5.

The First Amendment and Individual

Freedoms

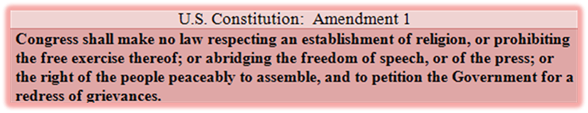

The First Amendment lists five of the most important

civil liberties enjoyed by Americans. They

include the freedoms of religion, speech, press, petition and assembly.

Freedom of Religion

The First Amendment presents two facets of freedom

of religion. First, in what is called

the establishment clause, the

government is prohibited from requiring or supporting a specific religion. Since most European countries had one

official religious institution, which people were forced to support, the

Founding Fathers understood that this policy could result in discrimination and

persecution. Thomas Jefferson referred

to this clause in the Constitution as a “wall of separation” between the church

and the state. Questions concerning the

meaning of the establishment clause have triggered a number of cases before the

Supreme Court. Many of these have

involved schools and religion. For

example, the principal of Nathan Bishop Middle School asked a rabbi to speak at

a graduation ceremony. It was a common

practice in the area to invite clergy for benedictions and invocations at

school-related functions. A parent of

one of the students at the middle school took the matter to court on the

grounds that it violated the establishment clause in the First Amendment. In 1991, the Supreme Court heard the case of Lee v. Weisman and ruled that clergy who

offer prayers in public school ceremonies are in violation of the

Constitution. To hear about this case

from the point of view of the Weisman family, click on the picture below.

The second aspect of freedom of religion addressed

in the First Amendment is derived from the words “…or prohibiting the free

exercise thereof”. This phrase, called

the free exercise clause, guarantees

Americans the right to practice whatever religion they choose without

government interference. Sometimes,

however, religious practices and rituals may conflict with public safety and

health. In these situations, the

government can apply certain restrictions without violating the

Constitution. The Supreme Court has made

a number of rulings that define the right of worshipping freely or not

worshipping at all. Thomas v. Review Board of the Indiana Employment Security Division

is one such case. In 1980, the Blaw-Knox Foundry & Machinery Co. shifted operations in

one of its plants to the manufacture of weapons. Because his faith prevented him from

producing arms, Eddie Thomas, an employee, asked to be laid off. The request was granted, and he applied for

unemployment benefits. Since it did not

believe that his reasoning was justified, the Indiana Employment Security Division

denied his claim; then, Thomas filed a lawsuit based on the free exercise clause. In 1989, the Supreme Court heard the case and

ruled that the state of Indiana had violated Thomas’ First Amendment rights.

Evangelical Lutheran Churchwide

Assembly

Freedom of Speech

Freedom of speech has long been considered the

cornerstone of American democracy. For

citizens to be informed and to participate in the decision-making process, they

need to hear and to discuss a variety of opinions. The concept of speech has expanded over the

years to include many forms of expression, such as films, television

broadcasts, books and telephone conversations.

Social media and email are also under this broad umbrella. Even though freedom of speech is protected by

the Constitution, it does have limits.

Exactly what these limits are is continuously being defined by the

courts. Judges must sometimes balance

free speech against national security and public safety. Types of expression that the Supreme Court

has ruled not protected in most situations by the First Amendment include the

following:

Ø Causing panic: During World War I, Charles Schenck mailed distributed a large number of flyers

criticizing the use of the military draft.

This resulted in his arrest. He

believed that his First Amendment rights had been violated and filed a

lawsuit. When his case reached the

Supreme Court, the justices ruled that his conviction did not violate the

Constitution. When he wrote the majority

opinion for this case, Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes stated the

following: “The most stringent

protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting ‘Fire!’

in a theater and causing a panic.” This

established the principle of weighing free speech against public safety.

Ø

Obscenity: The idea of obscenity is one of the most

controversial aspects of the First Amendment.

Since what is obscene to one person may not be obscene to another, it

represents a continuous challenge to the court system. When writing the majority opinion in the case

of Miller v California, Chief Justice

Warren Burger established a list of guidelines, known as the Miller Test; it is

still being used to decide what questionable material is protected as free

speech. Social media and technological

innovations continue to create new concerns requiring the court’s

interpretation of the First Amendment.

Ø

Defamation: Defamation is a basic term for attacks on

another person’s name, character or reputation.

If it is in spoken form, such as a public speech or a radio address,

this type of defamation is called slander. When it appears as written remarks in

newspapers or other printed media, it is known as libel. However, valid

criticism of politicians and celebrities is considered an appropriate use of

free speech. The landmark decision in

the case of New York Times v. Sullivan

(1964) emphasized this point. A civil

rights group paid the New York Times

to print an advertisement concerning the actions of the police department in

Montgomery, Alabama. L.B. Sullivan, the

police commissioner, sued the newspaper on the grounds that he had been

libeled. When the case reached the

Supreme Court, the justices decided in favor of the New York Times, but they also noted that the First Amendment does

not cover statements made with “actual malice” or “reckless disregard for the

truth”.

Freedom of Speech

Ø Fighting words: Fighting words are those expressions that,

when spoken, inflict injury and destroy the peace. To a degree, they are protected by the First

Amendment. If the danger to the public

is “clear” and “imminent”, law enforcement can limit the right of free

speech. Brandenburg v Ohio makes this point. Charles Brandenburg was a Ku Klux Klan

leader, who staged a rally in Ohio. He

refused to follow a police order to clear the street, and Brandenburg was

arrested. When his case reached the

Supreme Court, his right to free speech was upheld because there was no immediate

danger that the crowd would riot.

Ø Sedition: Sedition refers to words that are used to

incite rebellion or to promote the overthrow of the government. Espionage, treason, and sabotage are all

forms of seditious speech, but the meaning of these terms has also been defined

by a number of court decisions. In the

1950s, Oleta Yates and other members of the Communist

Party were convicted of advocating the overthrow of the United States

government. After a number of appeals,

the case reached the Supreme Court in 1957.

When the justices ruled in favor of Yates, they noted the difference

between speech that expresses a theory or an idea and speech that encourages

others to break the law. Discussions

concerning ideas and theories are protected under the First Amendment;

organizing a revolution or a riot is not.

Freedom of the Press

Americans consider freedom of the press to be an

important component of a democratic society.

Articles from printed and electronic sources foster constructive debate, encourage investigative reporting and present

different points of view. They can also

threaten national security, promote obscenity and make false statements in the

name of advertising. Along with the

power to inform, the press also has the power to distort. As a result, judicial rulings have expanded

freedom of the press in some areas and limited it in others. The case of New York Times Co. v. United States is one example. The New York Times and the Washington Post

received copies of a classified report known as the Pentagon Papers from Daniel

Ellsburg, a government employee. When the newspapers began to publish these

documents, the Nixon administration tried to stop them by filing a

lawsuit. The Supreme Court ruled on the

case in 1971 and upheld the publishing company’s right to print the Pentagon

Papers under the First Amendment. The

majority opinion noted that the government failed to prove a genuine threat to

national security.

New York Times Offices:

Photo Credit--Jleon

Conflicts between the government and the press have

also developed over revealing the sources for news stories. Reporters insist that naming their informants

or forcing them to testify in court is an unfair limitation on a free

press. The Supreme Court, on the other

hand, has not extended the First Amendment to cover the sources of

journalists. In 1972, Earl Caldwell, a

reporter for the New York Times,

refused to give testimony before a federal grand jury about the operations of a

radical political group, the Black Panthers.

He asserted that a court appearance would end his access to certain

confidential sources. The Supreme Court

ruled that criminal investigations override a reporter’s right to

confidentiality. Some states have passed

laws that name conditions under which a reporter may not be required to testify

in state courts. These are called shield laws; however, they do not apply

in federal cases.

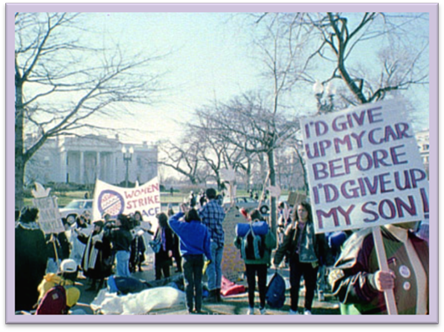

Freedoms of Petition and Assembly

The last section of the First Amendment addresses

the right to assemble and to petition.

Freedom of assembly includes participation in marches, parades, protests

and picket lines. The Constitution specifies

that these must be peaceful gatherings.

Like all the freedoms addressed in the First Amendment, the right to

assemble is limited by concerns for the public safety. For example, protestors are not permitted to

disrupt rush hour traffic or to obstruct airport runways. Participants do not have the right to loot

stores, to start fires or to take over public offices. Sometimes it is not the protestors who are

disorderly, but the bystanders. Hecklers

disturb the scene by shouting insults or by interfering with the

demonstrators. In these instances, law

enforcement may put a stop to the assembly for the sake of public safety. Generally, people can legally assemble in

areas supported by tax dollars. Parks,

sidewalks, state capitol grounds and national monuments have served as sites

for demonstrations. Court rulings have

restricted the public venues that may be used for this purpose. Harriet Louise Adderly

and a group of thirty-one other students from Florida A & M University

conducted a protest inside a local jail without permission. The sheriff asked them to leave, and the

group refused. The students were

arrested and were charged with trespassing.

When their case (Adderly v. Florida) came before the Supreme

Court in 1966, their convictions were upheld.

The majority opinion explained that, even though jails are public

institutions, they are built for security reasons and inappropriate for

protests.

Freedom of Assembly

Unlike the other provisions of the First Amendment,

very few court cases have interpreted the right to petition. It is simply a way to encourage or to

disapprove of a government action.

Lobbying, letter-writing, e-mailing and collecting signatures are all

acceptable means to exercise the freedom of petition. Although this right is

often taken for granted, the process of petitioning helps to ensure that

leaders listen to the people, even when they would prefer to do otherwise.

![]() Go to Questions 6-14.

Go to Questions 6-14.

The Second Amendment and the Right to

Bear Arms

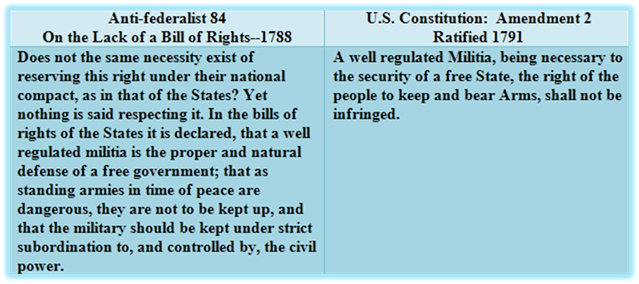

When congressmen first prepared to send a list of

proposed amendments to the states, the Revolutionary War and British tyranny

were fresh in their minds. The Second

Amendment, based on the language of the Anti-federalist arguments, limited the

power of the federal government by addressing the necessity of state militias

and the right to bear arms.

Does this amendment simply acknowledge the idea that

the federal government cannot outlaw state militias, or does it mean that, in

the tradition of the minutemen, every citizen is part of the militia and has a

right to bear arms? For the most part,

the courts have upheld that this privilege applies to individuals, but the

Supreme Court’s ruling in the case of the United

States v. Miller (1939) supported the right of Congress to pass gun control

legislation. The Second Amendment

continues to be controversial as Americans debate the impact of assault

weapons, mandatory background checks and the availability of ammunition.

![]() Go to Questions 15 and 16.

Go to Questions 15 and 16.

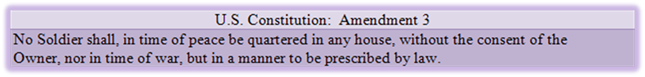

The Third Amendment and the Quartering

of Soldiers

Before the American Revolution, the British demanded

that their soldiers be housed and fed in the homes of the colonists. Since there were few inns and little time to

build barracks, this seemed to be a practical solution. However, the colonists deeply resented this

invasion of their privacy and the additional household expense. Many citizens of the new country believed their

property needed to be safeguarded. The

Third Amendment promises that United States citizens will not be forced to keep

soldiers in their homes during peacetime without their consent. It also, along with the Second Amendment,

reinforces the principle of limited government.

What’s

Next?

The amendments discussed in this unit consider the

personal rights of individuals and offer protection from government

interference. They are intended to

provide the necessary freedom of self-expression to the people they serve, but

they are not without limitations and restrictions. The rights guaranteed by the First Amendment

are not absolute; they must be balanced with respect for the rights of others. The Anti-federalists believed that citizens

needed protection from unwarranted searches, unwanted invasions of their

property and unfair treatment of accused persons in court. These things are also covered in the Bill of

Rights. Can the government take private

property for public use? Can you be

tried twice for the same crime? Does the

accused have the right to confront those who witness against him? We will consider all of these issues in the

next unit. Before continuing, review the

terms found in throughout this unit and complete Questions 17 through 26.

![]() Go to Questions 17-26.

Go to Questions 17-26.

Below are additional educational resources and activities for this unit.