THE COLD WAR: PART 2

Stamp Commemorating

Laika, the Soviet Space Dog

Unit

Overview

As

the 1950s progressed, the superpowers continued to battle for supremacy. Although the Cold War was usually fought on

economic and political fronts with little direct confrontation between the

United States and the Soviet Union, it became a hot conflict in Korea in

1950. The death of Joseph Stalin brought

Nikita Khrushchev to power. This Soviet

leader faced off against John Kennedy in the Cuban Missile Crisis, an event

that had the potential to plunge the world into nuclear war. The space race brought on an intense

competition, which ended when the two nations collaborated on the Apollo-Soyuz

Project in 1975. Let’s see how it all

happened.

STOP: Go to Section A Questions

The

Korean War

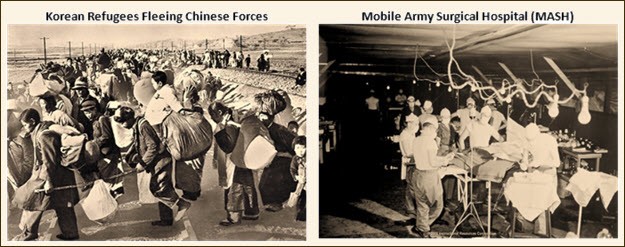

As

tensions between the superpowers increased in Europe, the Cold War spread to

Asia. Korea, which had been absorbed by Japan

prior to World War II, became a hotspot.

When Japan surrendered in 1945, Korea, like Germany, was divided at the 38th parallel into Soviet and American

zones of occupation. Residents of both

zones claimed the right to unify the peninsula.

By 1948, the Soviet zone had adopted a communist government while the

American zone remained firmly anticommunist.

Fears of a worldwide, communist conspiracy spread. Tension further escalated when China established a communist government

in 1949. This also made Americans even

more determined to pursue the policy of containment

and set the stage for a military response after Soviet-backed, North Korean

forces invaded South Korea in June of 1950.

Following

the attack, the United Nation’s Security Council met immediately without the

Soviet Union, which was boycotting council meetings at the time. The United States called on the U.N. to

demand the withdrawal of North Korean forces and to enforce this measure with

military action, if necessary. Since the

Soviets were not present to exercise their veto power, the resolution passed

the Security Council. Nevertheless,

North Koreans chose to ignore the ultimatum.

The Security Council approved the use of military force in Korea and

received commitments to send troops from sixteen countries. The United States, however, provided the

majority of troops and equipment; U.S. General

Douglas MacArthur was appointed commander of the United Nation’s forces.

The

war proved to be a bitter, bloody conflict.

In the beginning, the North Koreans seized control of most of the Korean

peninsula. The South Korean and U.N.

troops responded by driving their enemies above the 38th parallel. This forced the North Koreans to retreat to

the Chinese border. At this point, China

intervened and pushed the opposition southward.

The war seesawed back and forth until a fragile peace agreement was

reached in 1953. The 38th parallel

remained the dividing line between the two Korean states. North Korea continued as a communist nation,

but the United States achieved its goal of containing communism above the 38th

parallel. South Korea maintained its

democratic government, and the superpowers avoided a direct confrontation with

no risk of nuclear combat.

STOP: Go to Section B Questions.

De-Stalinization

Although

the Soviet Union emerged from World

War II as a superpower, the Russian people continued to experience a low

standard of living. Shortages of food,

fuel and necessary consumer goods were common.

Many were victimized by Joseph Stalin’s ruthless policies that were

enforced by secret police, purges and sentences served in labor camps. Following the death of Stalin in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev emerged as the new Soviet leader. Although he did not advocate a change in his

country’s goals, Khrushchev did pursue what he called de-Stalinization and criticized the former leader’s abuse of

power. In spite of objections from

Stalin’s supporters, he pushed to ease the tension brought about by the Cold

War and suggested peaceful co-existence with the West.

This

did not, however, include a more permissive attitude toward Eastern

Europe. Khrushchev sent tanks and other

heavy military equipment to put down a revolt in Hungary in 1956 and dealt harshly with his critics within the

Soviet Union. The Hungarians hoped that

the United States would come to their aid.

Since this did not happen, they had little choice but to continue their

subservience to the Soviets. The deaths

of the revolt’s leaders and the imprisonment of over 22,000 participants

underscored this point. By 1960,

Khrushchev’s favorable comments regarding peace were often mixed with hostile

statements toward the United States and Western Europe.

Fidel

Castro (left) and Nikita Khrushchev (right):

1961

STOP: Go

to Section C Questions.

The Cuban Missile Crisis

Direct

confrontations between the superpowers seldom occurred during the Cold War, but

the Cuban Missile Crisis was a

notable exception. In the 1950s, Cuban

society mostly consisted of a relatively few, very rich individuals and a large

number of very poor individuals. For

some young Cubans, socialism seemed a better alternative than the corruption

and oppression offered by the country’s dictator, Fulgencio Battista. Their

first attempt to overthrow Cuba’s government failed, but several of the rebels

managed to flee to Sierra Maestra, a remote, mountainous region of Cuba. Here, they educated themselves and studied

the tactics used by other revolutionaries.

They gained the support of many poverty-stricken Cuban peasants. Under the leadership of Fidel Castro, the

rebels overthrew the government and took charge. To strengthen his position, Castro tried

those who were accused of abusing the poor and executed them. He also nationalized all American companies

doing business on the island and used the money for reforms, such as the

creation of a national healthcare system.

In

the meantime, some Cubans fled to the America and claimed that, in reality,

Castro was no better than Battista. The

United States responded by declaring a trade embargo against Cuba and refused to buy Cuba’s most lucrative

export, sugar. Fidel Castro’s philosophy

shifted from socialism to communism when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

offered to buy Cuban sugar. This

resulted in a Soviet ally and pro-communist nation only ninety miles from the

state of Florida. President John Kennedy, consistent with the U.S.

policy of containment, agreed to support a group of anticommunist Cuban exiles,

who landed on the island near the Bay of

Pigs in 1961. Castro’s military

annihilated the rebels and quickly ended their attempt to remove the communist

dictator from power. The incident not

only provoked the further deterioration of U.S.-Soviet relations, but it also

encouraged the suspicion of sabotage between the superpowers.

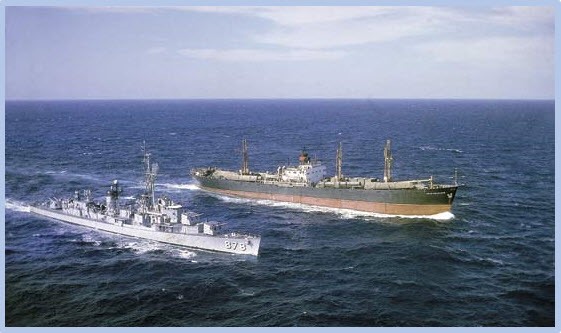

U.S. Intercepting a Russian Carrier

during the Cuban Missile Crisis

In

1962, photographs taken during the flight of a U-2 spy plane over Cuba revealed

the construction of a base for intermediate-range missiles with nuclear

capability. American intelligence

revealed that Soviet ships were heading toward Cuba with more shipments of

missiles. In total, the Soviets sent

forty-two medium-range missiles and twenty-four intermediate ones along with

22,000 military personnel. For

Khrushchev, this seemed a logical response to U.S. missiles close to the Soviet

border in Turkey and an attempt to

overthrow a communist government. The

United States sent two letters of protest to the Soviet Union and placed a type

of naval blockade known as a quarantine

in the path of the Soviet military cargo ships.

News organizations broadcast reports of the crisis around the world, and

the fear of a nuclear war reached global proportions. Rather than risk a direct military

engagement, the Soviet ships altered course and returned to the Soviet

Union.

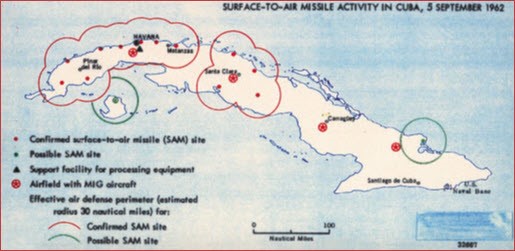

Map Showing the Placement of Soviet Missiles

in Cuba: 1962

The

Soviets agreed to remove all of their missiles from Cuba, an action that was

completed within two months. The United

States ended its naval quarantine and promised never to invade Cuba again. The U.S. missiles sites located in Turkey

were also dismantled. Another outcome of

the Cuban situation was the installation of a direct telephone line between

Moscow and Washington D.C. to ease communication between the superpowers in

times of crisis. The final result was

viewed as a success for the Kennedy administration, but it contributed to the

political downfall of Nikita Khrushchev in 1964.

STOP: Go to Section D Questions.

The Space

Race

In

October of 1957, Soviet technicians launched Sputnik, the first satellite, into the earth’s orbit. About the size of a beach ball, this shiny,

metal orb, trailed by four antennas, quickly followed the successful Soviet

test of a hydrogen bomb and made headlines around the world. Americans concluded that, if the Soviets had

rockets powerful enough to put a satellite into orbit, they also had rocketry

capable of striking the continental U.S. with nuclear warheads. This was enough to convince the American

public to support the allocation of millions of tax dollars to overtake the

Russians in the space race. The Soviet

Union was equally dedicated to maintaining its lead and also spent vast amounts

of money on its space program.

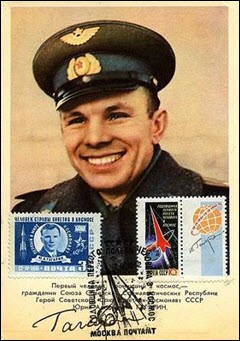

Cosmonaut

Yuri Gagarin

For

the next two decades, the superpowers engaged in a number of technological and

engineering firsts. In the fall of 1957,

the Soviet Union launched Sputnik II and sent Laika, a Russian dog, on a quick space flight. The United States followed with its first

successful satellite venture, Explorer I,

in early 1958. President Eisenhower

authorized the creation of the National

Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the agency soon sent up

the world’s first communications satellite. In 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space when Vostok I carried him on an orbit around

the earth. Later that same year, the

United States responded by sending Alan

Shepard on the first American manned space flight and with the Friendship VII mission, which completed

three orbits with astronaut John Glen

aboard in February of 1962. President

John Kennedy, determined to put the United States in the forefront of the space

race, announced the intent of putting a man on the moon by the end of the

decade, and this became a reality in 1969.

The space race drew to a close in 1975 with the Apollo-Soyuz Project, a collaborative effort shared by the

superpowers and the first of many combined aeronautic ventures. Although it sometimes increased Cold War

anxiety, space exploration and its accompanying technology has produced global

benefits in the areas of telecommunications and computer science.

STOP: Go to Section E Questions.

What

Does It All Mean?

The

Cold War rivalry and the fight for international superiority was fueled by the

events of the 1950s and 1960s. Military

operations in Korea, an intense confrontation over Cuba and an expensive but

productive space race all served to intensify the distrust between the United

States and the Soviet Union. Both sides,

however, remained wary of being the first to deploy nuclear weapons. The United States continued to operate based

on the policy of containment, and the Soviet Union maintained its determination

to achieve security. By the 1970s,

however, the Cold War would draw the United States into Vietnam and the Soviets

into Afghanistan. These long, costly

conflicts would prove difficult to win by traditional military tactics.

Additional Resources and Activities

The Start of the Space Race (article with quiz)