THE EXPANSION OF IMPERIALISM

Unit

Overview

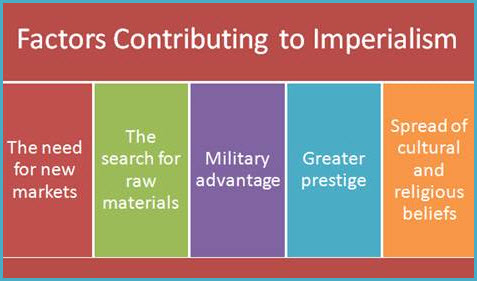

The

world’s industrialized nations quickly recognized that they needed raw

materials and new markets if they were to continue their economic success. The nations of the West competed to create colonies

in the underdeveloped regions of the world and became a force in Africa, Asia

and Latin America. This process became

known as imperialism. Their desire to

control additional territory grew from a strong sense of nationalism as well as

an obligation to further European values and religious beliefs. Books and newspapers inspired an interest in

distant places and a spirit adventure.

Let’s see how it all happened.

STOP:

Answer Section A Questions

New

Nations Upset the Old Balance

In

the decades following the American Revolution, many in Great Britain started to

feel that colonies were more trouble than they were worth. As a result, by the 1840’s, the British

government had granted both Canada and Australia a large portion of

self-rule. Yet, by the turn of the

century, Britain’s role in the world had changed, and controlling an empire

became more important than ever before.

In

the first half of the nineteenth century, the nations of Europe attempted to

create a balance of power through a system known as the Concert of Europe. Statesmen

hoped to achieve stability and peace through diplomacy and alliances. However, in the second half of the nineteenth

century, this idealistic view was replaced by a philosophy of power politics

and violence known as Realpolitik. Camillo

di Cavour, a skilled practitioner of Realpolitik, succeeded in unifying Italy while Otto von Bismarck

created the nation of Germany using

the same principles. In the era

following the Civil War, the United

States experienced rapid growth and emerged as a contender in the expanding

industrial market. These three countries

represented a new political and economic challenge for the established nations

of Europe. Citizens developed a loyalty to and love for their individual

countries which became known as nationalism. This new form of national pride encouraged

competition and bitter rivalries.

STOP: Answer Section B Questions

The

Race for Colonies

The

British soon found themselves in an intense struggle for economic

supremacy. Countries that had once

bought their products willingly were now adding taxes in the form of tariffs in

order to protect their own industries.

It was necessary for the British to retain their pre-existing markets

and to find new ones if they were to remain a world leader. New industries required a variety of raw materials that colonies

supplied. Businessmen also hoped lands

under British rule would provide new markets and new customers for their

manufactured goods. Extending the empire

also gave Great Britain the ability to protect trade routes which were also

necessary if the British were going to avoid an economic downturn.

Britain

believed establishing colonies for prestige and profit was the answer to this

dilemma. This quest for colonial empires

in order to gain political, economic and military power became known as imperialism. Other countries followed Great Britain’s

lead, and the race for colonies began in earnest. Countries that had colonies set out to

increase their empires, and countries that had no colonies were determined to

acquire them. By 1900, the French had

established an empire second only to Great Britain, and the Dutch expanded

their control over lands outside of Europe.

Both

Portugal and Spain tried to build new empires to replace their former

holdings. Russia moved into Central Asia

and Siberia while Austria-Hungary exerted its influence in the Balkan states. Belgium and Italy also became competitive for

colonies in both Africa and Asia. The

Germans invested in building a railroad from Berlin to Baghdad with the hope of

establishing a presence in the Middle East.

Japan and the United States also became involved in expansion beyond

their borders at this time. The

development of the rapid-firing machine gun gave the military forces of the

industrialized nations a distinct advantage.

Quinine provided protection

against malaria which had often been fatal for Europeans in the past. Distance was no longer a limiting factor. Steam ships, telegraph lines, railroads and

other inventions permitted nations to keep in touch with their colonies in

spite of the miles that separated them.

STOP: Answer Section C Questions

Profit

was not the Only Motive

However,

profit was not the only motive that inspired the race for colonies. European nations believed that additional

territory increased their prestige and status.

Some countries claimed land that offered very little economic benefit

simply to have a greater presence on the world map. Europeans were also convinced that they had

an obligation to carry the progress and the achievements of the Industrial

Revolution to areas of the world which they considered to be primitive. Christian

missionaries also pushed for expansion because they believed that European

rule was the best way to end practices such as the slave trade.

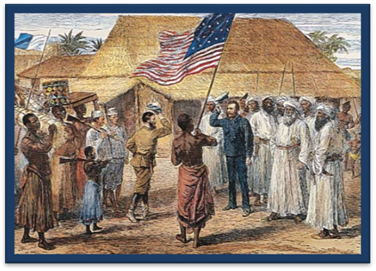

Stanley and Livingstone in Africa

Newspapers,

books and poetry also served to draw the average person into the imperialistic

view. An American newspaper hired Henry Stanley to travel to Africa and

look for David Livingstone. Livingstone had ventured into the interior of

Africa to find evidence against the slave trade and had not been heard from for

several years. Stanley found

Livingstone, interviewed him, and made headlines around the world. His articles captured the imagination and

interest of readers everywhere. Both

children and adults were equally fascinated by works of Joseph Rudyard Kipling who wrote stories and poems often set in

India. Although Kipling’s writings

sparked a true spirit of adventure, they also promoted an image of European

superiority and the concept that the European ways were best.

STOP: Answer Section D Questions

The

Scramble for Africa

The

nations of Western Europe as well as the United States and Japan were

determined to exert their power and influence.

As a result, imperialism changed life and altered the environment on

almost every continent. Some of the most

intense competition for colonies occurred in Africa. In 1875, Europeans

controlled ten percent of the continent.

Twenty-five years later, ninety percent of Africa was under some form of

colonial rule. The struggle intensified

in 1879 when Henry Stanley returned to Africa and claimed much of the interior

for King Leopold II of Belgium. Suddenly, the tiny nation controlled an area

that was eighty times larger than the country itself and referred to its new

acquisition as the Belgian Congo.

Not

to be outdone, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Italy, Germany and Britain

hurried to carve African territory for themselves. To prevent a war over colonial interests in

this region, European countries sent representatives to Berlin in 1885 to establish

ground rules for their presence in Africa.

As a result, nations could claim land in Africa by simply sending troops

to control strategic locations. It is

also important to note that no African leaders were invited to participate in

these discussions. The map pictured here

shows the impact of this policy.

The Partition of Africa in 1914

Although

Ethiopia and Liberia remained independent, the rest of Africa was quickly

divided among the nations of Western Europe.

Some industrialists thought that Africans would soon be purchasing goods

manufactured in Europe in large quantities.

However, most of these sales never materialized since the tropical climate

simply made European clothes impractical.

The real financial benefit came from the abundance of natural resources

and commercial plantations. Cocoa, rubber and palm oil were grown

as cash crops and significant exports.

The French controlled West Africa,

and the British managed the land near the Suez

Canal to protect their access to India. The Belgian Congo contained massive deposits

of tin, copper and manganese, but

these would seem small in comparison to the discovery of gold and diamonds in South

Africa. It was the domination of the southern tip of

the continent that would prove invaluable.

When

the British took control of the Cape of

Good Hope in 1806, a small group of Dutch settlers, who called themselves Boers, were already living there. They resented British authority and wanted

their own government. Large numbers of

Boers made their way further into the interior on a journey called the Great Trek. They came into conflict with the Africans or

Zulus, and the two groups fought for several years. After defeating the Zulus, the Boers set up

three small states named Transvaal, the

Orange Free State and Natal. Within

a short time, the British annexed Natal but permitted the other two countries

to remain independent.

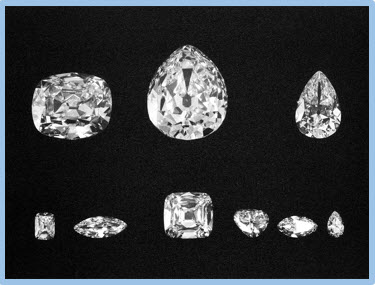

Diamonds Mined in South Africa

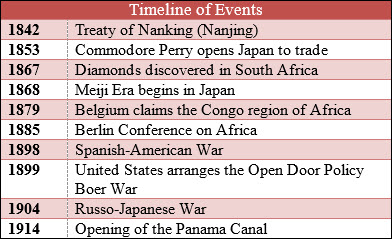

In

1867, Britain’s attention was directed toward a new venture. Diamonds were discovered on a farm near the

village of Kimberly located on the

border of the Orange Free State. British

miners made their way to the Boer lands in ever-increasing numbers, especially

after gold was discovered in the Transvaal in 1886. Tensions escalated, and the Boers declared

war against the British in 1899.

Although the Boers were outnumbered, they were successful in their use

of guerrilla tactics against the British army.

The British struck back by destroying Boer farms and food supplies, and

the Boers had little choice but to make peace.

In an effort to prevent further turmoil, the British permitted the

Dutch-speaking farmers to keep their own language and helped them rebuild their

farms. Native Africans, whose farms had

also been destroyed, were ignored. Soon

the Kimberly diamond fields, controlled by Cecil

Rhodes, were producing ninety percent of the world’s diamonds.

STOP: Answer Section E Questions

Spheres

of Influence in China

When

the nineteenth century began, China

was a prosperous, self-sufficient country.

In spite of its growing population, the Chinese developed an efficient

agricultural system. China believed that

products manufactured in Europe and the United States were inferior. As a result, the Chinese only permitted

European ships at the port city of Canton

(Guangzhou) and had little interest in what the outsiders had to offer. Europeans were determined to find something

the Chinese would buy. Unfortunately,

the product proved to be opium. Made from the poppy plant, this

highly-addictive drug created a major problem.

The

Chinese repeatedly requested that the nations of Europe stop the opium trade,

but Europe ignored these pleas. In an

attempt to use force, China began the Opium

War but was quickly defeated by the superior power of the British

navy. The Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing) ended the war but humiliated

China. China was required to open four

additional cities as trading ports and to pay for any opium that was destroyed

during the war. British citizens who did

business in china were granted extraterritorial

rights which meant they did not have

to obey Chinese laws.

Signing the Treaty of Nanking

Problems

continued to mount for the weakening Chinese government. For example, the agricultural system could no

longer keep up with the ever-expanding population. Meanwhile, European countries as well as

Japan established spheres of influence. These were areas of the country where a

specific foreign nation controlled the business interests and resources. The United States became increasingly

concerned that it would be shut out of the vast Chinese market. Therefore, the Americans proposed the Open Door Policy in 1899. As a result, China was not divided into

traditional colonies, and all nations were welcome as traders. In spite of this practice, the Chinese were

still at the mercy of foreign influence.

STOP: Answer Section F Questions

Japan

Joins the Empire-builders

As

the search for new markets and trading partners continued, Japan captured the attention of Europe and North America by

1850. Having enjoyed a long period of

peace and stability, the Japanese had little interest in establishing contact

with the West. Dutch traders were

permitted to maintain an outpost near the city of Nagasaki, but the Japanese response was limited. This picture changed in 1853 when Commodore Matthew Perry arrived with

his American fleet and modern weapons.

The Japanese knew they were not strong enough to drive out these forces

so they quickly agreed to a treaty. The

Japanese feared their independence would soon be lost so they formed a plan to

combat the foreign threat. A group of

powerful new leaders overthrew the government and named a fifteen-year old boy Emperor Mutsuhito. His regime became known as the Meiji or Enlightened Rule, and its goal

was the modernization of Japan.

Commodore Matthew Perry

Dramatic

changes came quickly to Japan during the Meiji Era. Feudalism was abolished, a new constitution

was adopted and Japan sent representatives to industrialized countries to study

their progress. With government support,

Japan built factories, increased coal production and re-negotiated trade

agreements in their favor. They earned

money from the sale of traditional goods like silk and financed their

industrialization with the profits.

Unlike China, Japan did not owe large sums of money to European and

American bankers. The new leadership

also focused on a strong military. They

patterned their navy after the British fleet and the army after the German

model. Their success was apparent in the

Russo-Japanese War in 1904. Japan defeated Russia in this series of

battles, and Japan was able to create a sphere of influence in Manchuria, a Chinese province. The Japanese quickly followed the European

example of empire-building as a means to access natural resources and new

markets.

Imperialism

Goes Global

Imperialism

reached all corners of the world and became global in nature. The Industrial Revolution created a demand

for raw materials that drew attention to Latin

America as well as Asia and

Africa. Bolivian tin, Chilean copper and

Argentine beef caught the attention of industrialized nations. As Latin America increased its output of

these products, it realized it needed improved transportation in the form of

railroad lines and better communication links to be profitable. South American nations borrowed heavily from

European and American banks to finance these improvements. As a result, foreigners were soon able to

take over key mines and industries. The

United States, Latin America’s largest investor, feared European nations would

soon take over weakened governments in this region and used the Monroe Doctrine to restrict their

influence. The Spanish-American War gave the United States control over Cuba

as well as Puerto Rico and offered America the opportunity to assert its

authority.

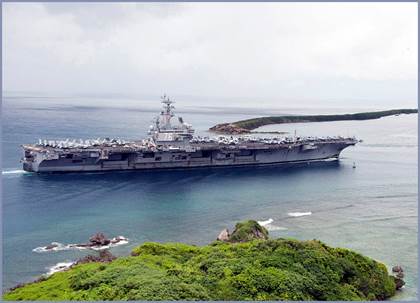

USS Ronald Reagan Docking in Guam

There

was also a fierce competition to control islands in the Pacific Ocean. An abundance of natural resources stirred an

interest in these territories, but their value as coal stations for steam

ships made them indispensable. The

settlement of the Spanish-American War awarded Guam to the United States; Britain, France, and Germany established

a presence there as well. By 1900,

nearly all the Pacific islands had lost their independence. Even the most remote parts of the world

became fair game for imperialists. The

early twentieth century produced a number of explorers who raced to Antarctica

to claim land for their respective countries.

STOP: Answer Section G Questions.

What Does

It All Mean?

Economic

gain, national pride and a desire to spread European values fueled the quest

for more territory and the rise of imperialism.

The decisions made by Western nations in the late nineteenth century

would prove to have serious consequences in the twentieth century. The competition for control of natural

resources led to increased tension, the threat of war and a disregard for the

environment. Millions of Asians,

Africans and Latin Americans were dominated by foreign powers which controlled

both the political and economic aspects of their lives. How would the indigenous people of the

non-industrialized nations react? Would

the ambitions of wealthy nations eventually lead to a major war? The decisions and events of the twentieth century

were shaped by these questions.

Additional Activities and Resources

The Meiji Restoration of 19th

Century Japan Article with Quiz

Writing Exercises: Imperialism I