ENLIGHTENED THOUGHTS BECOME ACTIONS

Independence Hall,

Philadelphia

STOP: Complete Section A Questions.

Enlightened

Despots

While

the writers and philosophers of the Enlightenment were busy with their pens,

most kings and queens of continental Europe were ruling as absolute

monarchs. Absolutism gave these rulers total control over their governments

and their people. In some cases, this

included a vast amount of serfs or

peasants who were obligated to do work on the properties of the

landowners. Unlike slaves, they could

not be sold but were obligated to remain with the land. As the ideas of the Enlightenment spread,

many individuals began to question the authority of their leaders and the

conditions of the citizenry. They

concluded that the skill of critical thinking could be used to turn governing

into a science; this would result in the creation of better laws and useful reforms. The philosophes had a practical side, and

they knew it was unlikely that monarchs would give up their power

willingly. Therefore, it seemed that

enlightened despots or monarchs with a clear understanding of the philosophy of

the Enlightenment were the best hope of improving society.

Imperial Crown of the

United Kingdom

How

did Europe’s rulers react to the ideas of the Enlightenment? Some, like King Louis XV of France, chose to ignore the whole movement and

censor the new writers. It was not an

effective practice, but it made them feel more secure. Other rulers, however, were caught up in the

spirit of the new thought and were impressed with the inspiring concepts

centered on reason and progress. These

enlightened despots often favored religious tolerance, legal reform and useful

projects. However, make no mistake, power politics always took precedence over

enlightened teaching. Let’s examine two

of the most prominent rulers who fit this description—King Frederick II of

Prussia and Empress Catherine II of Russia.

STOP: Complete Section B questions.

Palace built by Frederick the Great

King Frederick II of Prussia

Most of us would have enjoyed spending an afternoon

with Frederick II (also known as

Frederick the Great). He was witty,

brilliant and interested in almost everything.

Frederick lived modestly, at least by the standards set for the European

monarchs of his day, and he worked hard at the business of ruling. His attitude conveyed his desire to serve and

to strengthen the state, and his views were generally humane and liberal. Schools under his leadership improved, and

scholars were permitted to publish their findings. Religious tolerance of both Catholics and

Protestants became the norm.

However,

Frederick the Great never lost sight of the fact that the Prussian nobility was

the backbone of the army and the foundation of his power. This placed major limitations on his quest

for reform. For example, Frederick II

openly admitted that serfdom was wrong, but he did not want to offend wealthy

landowners by doing anything about it.

The concept of religious freedom did not extend to Polish and Prussian

Jews who were confined to small, overcrowded ghettos. Because he did not want to risk losing the

support of his military officers, Frederick reduced the use of torture but did

not abolish it. Although he preferred to

justify his reign with practical results and said little about divine right,

Frederick had no intention of jeopardizing his rule for the sake of the ideals

of the Enlightenment.

Catherine the Great

Empress Catherine II of Russia

One

of the most fascinating figures of the eighteenth century was Catherine II, Empress of Russia. Her thirty-four year reign was filled with

political challenges, intellectual advancements and intrigue. Influenced by the writers of the

Enlightenment, many of whom visited her court, Catherine called a

constitutional convention in 1767. She

invited nobles, townspeople and peasants in the hope of creating domestic

reform and new laws. However, when the

participants argued and accomplished very little, Catherine simply sent them

home and abandoned the whole idea of a constitution.

Although

she claimed to be an enlightened ruler, improving the lives of all the Russian

peasants conflicted with Catherine’s need to have the support of the

nobility. This became very obvious in

1773 when Catherine sent her armies to crush a massive uprising supported by

peasants, soldiers and escaped prisoners.

Catherine the Great was also committed to the territorial expansion of

her empire and, like her counterpart Frederick II of Prussia, ignored the

philosophe’s arguments against war. In

short, Catherine’s commitment to the teachings of the Enlightenment was more of

an intellectual pursuit than a political reality.

STOP: Complete Section C questions.

The

Enlightenment Crosses the Atlantic

In theory, Britain’s government, referred to as a limited monarchy, was considered the

best on the planet, at least according to the standards of the

Enlightenment. However, theory and

reality were two different things. The

king’s power was limited by a law-making body called Parliament. It was divided into two parts—the House of

Lords and the House of Commons. By its

very name, it seemed the House of

Commons should be a perfect example of democracy in action. Yes, its members were elected by popular

vote, but only men who owned the required amount of land were eligible to cast

a ballot. As a result, the House of

Commons was elected by five percent of the population. This small group of citizens favored

government policies that encouraged national economic expansion and individual

profits.

In

the eighteenth century, a country’s international status was directly related

to its gold supply. To accumulate gold,

a nation had to sell more products than it bought. The British concluded that

the key to prosperity was the establishment of colonies so they directed their

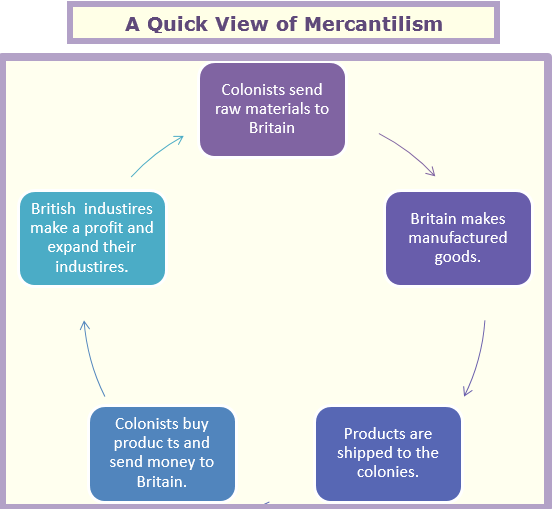

attention to winning and controlling them.

Britain directed colonial affairs based on the principle of mercantilism. This economic philosophy stressed the concept

that colonies existed primarily to enrich the mother country. In contrast, the American colonists saw

themselves as loyal British citizens who deserved the same rights and

privileges as their counterparts in Britain.

To understand how these differing views led to revolution, one needs to

simply follow the money.

STOP: Complete Section D questions.

The

American colonies served as a ready market for British manufactured products

and a cheap source for materials shipped to Britain by the colonists. To assure the system worked to their benefit,

the British passed the Navigation Acts

in 1660 and 1663. According to these

laws, the Americans could not sell their most valuable products to any country

other than Britain and could and could only buy products from other countries

if they paid high taxes on them. In an

attempt to circumvent the law, the colonists resorted to smuggling, and it was

difficult for the British to control.

Political

events in Europe pulled Great Britain into the Seven Years’ War and drew battle lines between the British and

French settlers in North America. After

the British brought the war to a successful conclusion, they reasoned that the

colonies should be responsible for a portion of the war debt since they

benefitted from the expensive military campaigns. Britain reasoned that a new tax required of

the colonists was a logical consequence.

The Stamp Act, which required

the colonists to pay for the stamping of legal documents such as deed and

wills, was so vehemently opposed it had to be repealed. As the British continued their attempts to

tax the American portion of the Empire, the colonists began to see themselves

in terms of the ideals of the Enlightenment.

They used the concepts of John Locke and other philosophers to justify

their objections to the activities of the British crown.

Eventually,

the situation became intolerable, and the Americans wrote the Declaration of

Independence based on violations of the social contract. Once they won their independence, Americans

again used the Enlightenment principles to set up a new government. The thoughts of Rousseau, Locke and

Montesquieu resulted in a system that drew its authority from the consent of

the governed. The Constitution stressed

a form of leadership based on the separation and the balance of powers. It was indeed the Enlightenment philosophies

that drove the American Revolution and the establishment of a new

government. These developments strongly

reflected the Enlightenment beliefs of reason and progress.

STOP: Complete Section E questions.

Jose de San Martin

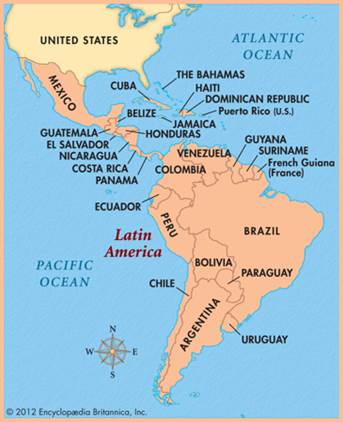

The

Enlightenment Moves South

The

Enlightenment ideas also impacted events in the southern parts of the Western

Hemisphere. The countries that colonized

these lands (Portugal, Spain and France)

all spoke languages derived from Latin so the regions of the Caribbean, South

American, Central America and Mexico were referred to collectively as Latin America. The population ranged from the enormously

wealthy to the extremely poor. People

who were born in the mother countries and held the most important offices were

known as peninsulares. Their control of the valuable import and

export trade was responsible for much of their financial success. Ranked next were the creoles who were born in Latin America to parents of European

origin. Most were rich landowners and

held less important government offices.

These two groups made up a mere twenty percent of the populace. The vast majority of the inhabitants

consisted of mestizos (individuals

of a European and Indian background), mulattos

(individuals of European and African background) and native Indians. The millions of Indians were considered the

lowest in respect to social status. They

were technically free but were treated no better than slaves. Their plight came to the attention of King Charles III of Spain who fit the

mold of an enlightened despot. He made

an effort to introduce reforms to benefit the Indians. However, the distance between Spain and New

Spain, as Spanish lands in South America were called, was great; laws were

difficult to enforce if the peninsulares did not agree with them. The fear of an Indian revolt encouraged the

neglect of these laws.

In

the meantime, the ideas of the Enlightenment began to drift into Latin

America. North American ships visited

South American ports staffed with sailors who sometimes brought copies of the

American Declaration of Independence and the Constitution as well as the

writings of Voltaire and Rousseau. The

Creole elite became familiar with these works and came to believe that certain

rights should be extended to them.

Creoles began to think of themselves as Americans rather than Spaniards.

This

new trend in thought led to a series of revolutions in Latin America from 1810

to 1830 and brought to the forefront two brilliant generals inspired by the

ideals of the Enlightenment, their Creole backgrounds and events in Europe as

well as North America. Simon Bolivar, known as El Libertador,

was a well-educated and well-traveled Venezuelan Creole. Having read the writings of Voltaire and

Rousseau along with those of Jefferson and Paine, he led revolutionaries in

Venezuela, Ecuador and Colombia. Jose de San Martín guided the military

activities of the patriots in Chile and Argentina. Their combined forces eventually drove out

the Spanish forces and inspired other regions of Latin America to seek

independence as well.

Although

Latin America included sixteen independent nations by 1830, political freedom

and government by the consent of the governed proved to be elusive goals. Some military leaders had come to enjoy the

power they had achieved during the struggles for independence. This led to a rise in dictatorships in most

Latin American countries. These rulers

were mainly concerned with increasing their own wealth and status; they did

little to improve the lives of average citizens and the members of the lower

classes.

Stop: Complete Section F Questions.

What

Does It All Mean?

The

Enlightenment inspired leaders and citizens to view government from a new

vantage point. Some absolute monarchs

saw it as a tool to assist in reforming their government and strengthening

their states. The revolutions across the

Atlantic Ocean changed the idea of forming a social contract from a possibility

to a reality. Rational human beings

could exercise individual freedom and maintain a representative

government. You will soon see that

events in North America strongly affected France as French officers returned to

their native country inspired by their tour of duty in North America.

Additional Activities and Resources for this Unit

Unit 3 Why Latin America Wanted Independence from Spain

(article with quiz)

Unit 3 Why Latin America Wanted Independence Organizer