![]()

![]()

![]()

ENTOMOLOGY (THE BUG

DETECTVE)

UNIT OVERVIEW: Forensic Entomology is an up and coming field in the world of crime solving. Forensic entomology was once used only to determine time or date of death. Insects now contribute to suspect movement in a variety of way. This unit will introduce entomology, various types of insects and their cycles, body decomposition, and the methods of collecting, preserving, and packaging insects, as well as an experiment on forensic entomology. Students will build a “Forensics Science Kit” from the list of common materials provided.

DIRECTIONS: Read the following text, look at the illustrations, complete the activities, and answer the questions. Key terms will be highlighted in bold print.

|

FORENSIC

SCIENCE |

|

- 3 pieces of raw beef liver |

|

- 2 Styrofoam plates |

|

- dishpan filled with water |

|

- plastic wrap |

|

- magnifying glass |

|

- tweezers |

|

- thermometer |

|

- safety goggles/glasses |

|

- exam gloves |

|

- notebook and pencil |

|

Key Terms |

||

|

forensic entomology |

entomologist |

ecological succession |

|

waves |

quantifiable terms |

initial decay |

|

putrefaction |

black putrefaction |

dry decay |

|

butyric fermentation |

dessicate |

carrion |

|

instar |

molts |

oviposted |

Introduction to Entomology ![]()

Insects are

the first to arrive at a dead body.

These insects provide vital testimony about the time of death. Forensic entomology has been practiced in

Forensic entomology, or Medicocriminal Entomology, is the study of the insects associated with a human corpse in an effort to determine elapsed time since death. An entomologist studies insects. Forensic entomology is based on the theory of ecological succession. This means that the insects that come to a corpse arrive in a predictable sequence. Entomologists have known for a long time that insect species follow a very specific pattern in life. This specificity allows the scientists to gauge the insect’s arrival at the site and figure out how long a body would have been there.

The

History of Insects

Obviously insects are never born fully developed in adult form. They have to come from somewhere, which is as either eggs or larvae. Either way, each species of insect progresses through the other stages of its life cycle at predictable times. Insects turn from egg, to larvae, to pupae, to adult with abrupt and predictable changes. Some insects lay eggs only at high noon, some lay eggs only indoors, or only in the shade, or only in the bright sunlight. Even the absence of insects can be forensic evidence.

Blowflies

The first insects to arrive are the glittery greenbottle blowflies. Their scientific name is Sarcophagi, meaning corpse eater. The blowfly prefers to lay eggs only in large mammals that have been dead a couple of hours. They begin to arrive within 10 minutes of death, feed on the still warm soft tissue, and lay eggs in openings such as the nose, eyes, mouth, and wounds. The eggs of the blowfly begin the hatch into larvae or maggots within 24 hours. The larvae feed on soft tissue, preparing it for the next wave of insects, beetles, which prefer dry flesh and bone. After feeding, the larvae will move off the body into the surrounding soil to develop into pupae. Predatory insects such as the rove beetle also come and prey on the insects feeding on the corpse. Each wave of insect invaders is a time marker and can be as accurate as a clock.

Blowflies are one of the most useful species to forensic entomologists, as they have a well-understood life cycle. Once the blowfly splits from its third skin, it will not grow anymore as it is an adult. Small flies aren’t younger than larger flies, they are just flies of a different species altogether, or two flies of the same species but of different sexes.

The length of time a blowfly spends at each stage has been studied extensively and under a variety of conditions. The forensic entomologist can roughly estimate the length of each stage under a controlled lab situation, and then adjust the schedule to account for actual conditions at the scene. Before determining how long a body has been dead, as opposed to how long insects have been infesting it, the entomologist must first have a good idea of when the first blowflies arrived and laid eggs on the body. Blowflies prefer about two days after death.

Blowflies aren’t native to all areas. Other species are studied as well so that experts can discover their cycle. Not all insects are attracted to a body at the same time. Some species prefer the freshly dead, others the well decayed. Some do not feed on the bodies, but on the molds forming on them, or on other insects that have been attracted to them. New arrivals that appear together, or at the same time, are sometimes referred to as waves, and a forensic entomologist would be able to gauge the normal progression, species by species, for his or her own region.

Keep in mind that an adult female blowfly will arrive at a body 10 minutes to 6 hours after death to lay her eggs. The eggs will hatch into larvae, or maggots, in 1 to 3 days. The larvae will feed on the body for 7 to 10 days. Next, the larvae will burrow into nearby soil and become pupae. They will emerge into adult flies in 10 to 12 days following the previous stage.

The Bug

Detectives

In order to determine when a wave appeared, it is not acceptable to say “three days after death” or “at a fresh corpse.” That would lead us to assume a set of normal conditions, and that every body decays at the same rate. Neither of these is true. Bodies that are frozen, decay at different rates from bodies inside oil drums or bodies found in the desert. The timeline of the entomologist must take into account the differing rates of decay. To make that possible, bodily decay is described in quantifiable terms, which means it is measurable. But even with the absence of outside mold, bacteria, worms, or insects, bodies rot from the inside. As with the life cycle of bugs, this process follows a well-documented path.

The

Stages of Bodily Breakdown

Initial Decay: On the outside, the corpse appears much as it did in life, but the process of decomposition has started due to the actions of the bacteria, protozoan, and nematodes that are already present in the body when it was alive.

Putrefaction: Gas formed by the activity of organisms within the body cause it to swell and smell.

Black Putrefaction: A bit of a misnomer, actually as the characteristic discoloration of the flesh accompanying this stage may be blue, green, purple, brown, or black. The swelling of the previous stage collapses again as that gas begins to escape. The swelling decreases, but the smell increases dramatically.

Butyric Fermentation: Tissues and organs now become fluid, fluid has escaped by a variety of means, and now the body will begin to dessicate, or dry out. Mold usually covers some or the entire exterior. A different kind of odor – not good, but not as “knock you over and send you gagging” as the previous one – is noticeable.

Dry Decay: Not mummification, but a slow process of continuous decay, during which time the tissues continue to rot, dry out, and shrink until skeletization has occurred.

Being able to associate a particular stage of death with a particular type of insect infestation also makes it possible to determine if a body was unavailable for insect infestation for some reason. If the blowflies like to infest bodies that are in the putrefaction stage and an examiner finds a body well past that stage, in an area where blowflies are habitually found, and there’s no sign of them or their remains on the body, the entomologist will consider the distinct possibility that the body was elsewhere at that time in the corpse’s history. Maybe it was moved from a sealed area after putrefaction was well advanced? Maybe it is winter and the blowflies aren’t around? Maybe the body went through that stage at night when blowflies are inactive?

If there are no insect larvae on a corpse that is lying outside, the police know that either death just occurred and not enough time has elapsed to attract insects or that death just occurred somewhere else and the body has been moved. It could also mean that the body has been frozen. Freezing a body temporarily stops all decomposition, and insects will not be attracted to it until it has thawed.

If the body was frozen for a period of time before being placed outside, the insects would only invade then, giving the misleading impression that death had just occurred. Forensic experts would be able to determine whether or not the body has been frozen, and insect evidence would still determine the time of exposure.

If the body had been buried deeply, most of the insects would be excluded. However, most criminal burials are not deep, as the intention is merely to conceal the body. Most insects would then dig down into the body, especially if blood had soaked into the soil. In this case, insect evidence could still be used.

If a body has been wrapped or packaged in some sort of way that would exclude insects, it would need to be completely secure.

The

Cycle of Life

The method of using insects for elapsed time since death is determined by the circumstances of each case. Entomologists use successional waves of insects when a corpse has been dead between a month up to a year or more. They use maggot age and development when death has occurred less than a month prior to discovery. The first method is based on the fact that a human body, or any kind of carrion, or decaying flesh of a dead animal, supports a very rapidly changing ecosystem going from the fresh state to dry bones in a matter of weeks or months depending on geographic region. During this decomposition, the remains go through rapid physical, biological and chemical changes and different stages of the decomposition are attractive to different species of insects.

The first insects are usually the blowfly, as mentioned earlier in this unit, and the housefly, or the Muscidae. Other species are not interested in the fresh body, but are only attracted to the corpse later such as the cheese skipper, or Piophilidae, which arrive later, during the stage of protein fermentation. Some insects are not attracted by the body, but rather on the other insects at the scene. Many species are involved at each decomposition stage and each group of insects overlaps the ones adjacent to it somewhat. Because of this, it is important for the entomologist to have knowledge of the regional insects and times of carrion colonization, etc. This information will help them determine a window of time in which death took place. As time since death increases, so does the window of time. A working knowledge of insect succession is necessary for this first method to be successful.

The second method, that of using maggot age and development can give a date of death accurate to a day or less, or a range of days, and is used in the first few weeks after death. Maggots are larvae or immature stages of two-winged flies. The insects used in this method are those that arrive first on the body. The blowflies lay their eggs on the corpse, usually in a wound, if present, or if not, then in any of the natural orifices, such as the mouth or other opening. Their development follows a set, predictable, cycle.

Maggots feeding on a piece of meat.

Maggots feeding on a piece of meat.

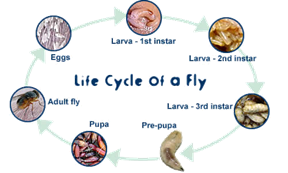

The insect eggs are laid in batches on the corpse. The eggs will hatch after a set period of time, into a first instar (or stage) larva. The larva feed on the corpse and moults (casts off or sheds) into a second instar larva. The larva continues to feed and develop into a third instar larva. The stage can be determined by size and the number of spiracles (breathing holes). During the third instar, the larva will eventually stop feeding and will wander away from the corpse, either into the clothes or the soil, to find a safe place to pupate. This non-wandering stage is called a prepupa.

The larva then loosens itself from its outer skin, but remains inside. The outer shell hardens, into a hard protective outer shell, or pupal case, which shields the insect as it metamorphoses into an adult. Freshly formed pupae are pale in color, but darken to a deep brown in a few hours. After a number of days, an adult fly will emerge from the pupal case and the cycle will begin again. When the adult fly emerges, the empty pupal case is left behind as evidence that a fly developed and emerged.

Each of these developmental stages takes a set, known time. The time period is based on the availability of food and the temperature. In the case of a human corpse, food availability is not usually a limiting factor. Insects are cold-blooded, so we know that their development is extremely temperature dependent. Their metabolic rate is increased with increased temperature, which results in a faster rate of development. Because of this development, decreases in a linear manner with increased temperature, and vice-versa.

An analysis of the oldest stage of insect on the corpse and the temperature of the region in which the body was discovered leads to a day or range of days in which the first insects oviposted or laid eggs on the corpse. This, in turn, leads to a day, or range of days, during which death occurred. For example, if the oldest insects are 7 days old, then the decedent has been dead for at least 7 days. This method can be used until the first adults begin to emerge, after which it is not possible to determine which generation is present. Therefore, after a single blowfly generation has been completed, the time of death is determined using the first method, that of insect succession.

Collecting,

Preserving and Packaging Specimens

The first and always most important stage of the procedure involved in forensic entomology involves the careful and accurate collection of insect evidence at the scene. This involves a knowledge of the insects behavior; so this task is obviously best performed by an entomologist. Most often, an entomologist is not called to the scene and does not see the body until after it has been removed from the death site. The evidence is dependent on accurate collection by the investigating officers or C.S.I. team.

Samples of insects of all stages should be collected from different areas of the body, from the clothing, from the soil/carpet, etc. Insects will quite often congregate in wounds and in and around natural orifices. The two main insect groups on bodies are flies and beetles. Both types of insect look very different at different stages of their lives.

Example of a carrion beetle.

Example of a carrion beetle.

Flies can be found as:

-

eggs (usually in

egg masses)

-

larvae or maggots

(in a range of sizes from 1-2 mm to 17 mm)

-

pupae and/or

empty pupal cases

-

adults

The eggs are very tiny, however, are usually laid in clumps or masses. They are usually found in a wound or natural orifice, but may also be found on clothing. To collect eggs, a child’s paintbrush is dipped in water, or forceps may be used. Maggots need to be collected in a range of sizes. They will be found crawling on or near the remains and may be in maggot masses. These masses generate a lot of heat, which speeds up development. Due to this, it is important to note the following:

-

the location of

the maggot masses

-

temperature of

each mass using a thermometer

-

if the

temperature cannot be obtained, estimate the size of mass

-

label which

maggots come from a particular mass

Keep in mind that larger maggots are usually older so are the most important, but smaller maggots may belong to a different species so both sizes should be collected, with of course, the emphasis being on the larger maggots. Collect samples from different areas of the body and the surrounding area, keeping them separate.

Beetles can be found as adults, larvae, or grubs, pupae and also as cast skins. All stages are of equal importance. Beetles move fast and are often found under the body, in and under clothing. Beetles are cannibals so cannot be placed together in the same vial.

Soil and leaf samples can also be useful. Collect approximately a coffee can-size of soil from under and from very near the body. If the soil below the body is extremely wet, it is better to collect the soil from near the remains.

The web site listed below offers more detailed information on collecting, preserving and packaging insect specimens. Since this is only an introductory course in forensics, there is not enough time to go into detail on every topic, however, sites for more detailed information will be provided when possible.

For additional information on preserving specimens click on this link PDF

File.

Facts

about the Death Site

The forensic entomologist needs to know the following facts about the habitat at the death site when analyzing insect activity:

|

- general – is it woods, a beach, a house, a roadside? |

|

- vegetation – trees, grass, bush, shrubs? |

|

- soil type – rocky, sandy, muddy? |

|

- weather – a time of collection, sunny, cloudy? |

|

- Temperature and possibly humidity at collection time |

|

- Elevation and map coordinates of the death site |

|

- Is the site in shade or direct sunlight? |

|

- Mention anything unusual, such as whether it is possible that the body may have been submerged at any time |

The entomologist also needs to know the following facts about the remains:

|

- presence, extent and type of clothing |

|

- Is the body buried or covered? If so, how deep and with what (soil, leaves, cloth) |

|

- What is the cause of death, if known? In particular, is there blood at the scene? |

|

- Or other body fluids? |

|

- Are there any wounds? If so, what kind? |

|

- Are drugs likely to be involved? This may affect the decomposition rates |

|

- What position is the body in? |

|

- What direction is the body facing? |

|

- What is the state of decomposition? |

|

- Is a maggot mass present? How many? This will affect the temperature on the body |

|

- What is the temperature of the maggot mass (s)? |

|

- Is there any other meat or carrion around that might also attract insects? |

|

- Is there a possibility that death did not occur at the present site? |

If the body has been refrigerated at the morgue, then the entomologist also needs to know the exact time that the body went into the cooler, and the exact time it came out. Photographs, or a video of the scene, with the body at the scene, and after removal of the body prove to be quite useful.

The

Importance of Weather

When determining the elapsed time since death, it is important to consider weather factors. Weather records from the nearest weather station should be collected, including temperature and precipitation. It is also important to note the distance between the death site and the weather station. Forensic meteorologists record the weather conditions, temperatures, wind speeds, wind direction, sun glare, movements of weather patterns, and even phases of the moon. More detailed information on forensic meteorologists will be discussed in a future unit.

More

Information on Entomology

None of the information derived from insects is foolproof. Insect timetables can be delayed or hurried. The variable is temperature.

C.S.I.’s also collect information from meteorologists about the temperature and weather conditions for the area where a body is found. Cool weather slows down insect activity and the growth of eggs and larvae. In winter, eggs laid inside a body will grow slower, and the larvae will stay inside a body longer in order to maintain their body heat. This situation results in a body that has decayed quickly on the inside but still has intact skin.

The position of a body can hinder insect activity. Insects can’t get at a body that is wrapped in a rug, sealed in a plastic bag, or buried, which delays the timetable, making insects as TOD indicators virtually useless. The length of time between death and discovery of a body, the less accurate the estimate using insect data will be. Accumulated insect casings can give an indication of how many insect life cycles have taken place, and in what season death occurred.

Bugs on the body are only half the story. Bugs found on clothing or even the car of a murder suspect could be the evidence placing him or her at the scene of the crime. Insects that are specific to a particular area can indicate where a body has been if it has been moved. Cocoons found on submerged objects can also give a time frame.

Entomologists bring live immature specimens back to the lab to be raised to adulthood. They are placed in an incubator that simulates the humidity and temperature of the crime scene. Sometimes a piece of flesh that the insects had been feeding on can be brought back in order to duplicate the insect’s diet. When the eggs hatch, the researcher can count back and determine when the first eggs were laid and how long the corpse had been at that location.

An entomology incubator found in a crime

laboratory.

An entomology incubator found in a crime

laboratory.

What

information can a forensic entomologist provide at the death scene?

Forensic entomologists are usually called upon to determine the postmortem interval of TOD in death investigations. They use a number of different techniques that includes species succession, larval weight, larval length, and a more technical method known as the accumulated degree hour technique. This last particular technique can be very precise if the necessary data is available. A qualified forensic entomologist can also make inferences as to a possible postmortem movement of a corpse.

Forensic entomologists can also use entomological evidence to help determine the circumstances of abuse and rape. Victims that are incapacitated often have associated body excretions that soak clothes or bed dressings. Those types of materials will attract certain species of flies that otherwise would not be recovered. Their presence can yield many clues to both ante mortem and postmortem circumstances of the crime.

Through new technology, the entomologist can use DNA technology not only to determine insect species, but to recover and identify the blood meals taken by feeding insects. The DNA of human blood can be recovered from the digestive tract of an insect that has fed on an individual. The presence of their DNA within the insect can place suspects at a known location within a definable period of time and recovery of the victim’s blood can also create a link between perpetrator and suspect.

The entomologist can recover insects from decomposing human remains and this can be a valuable tool for toxicological analysis. Toxicological analysis can be successful on insect larvae because their tissues assimilate drugs and toxins that accumulated in human tissue prior to death.

Other Uses for Insects in

Forensic Science

The following list identifies some other uses for insects in the field of forensic science:

-

The body may have

been moved following death, from the scene of the crime to a

hiding place. Some of the insects on the body may be native

to the first habitat

and not the second. This shows that the body was moved and also

gives an

indication of the type of area where

the crime actually took place.

-

The body may have

been disturbed after death, by the killer returning to the scene

of the crime. This may disturb the cycle of the

insects. The entomologist may be

able to determine not only the date

of death, but also the date of the return of the

killer.

- Decomposition may obscure

the presence and position of wounds.

Insects

colonize remains in a specific

pattern, usually by laying eggs first in the facial

orifices, unless there are wounds,

in which case they will colonize these first.

They will then proceed down the

body. If the maggot activity is centered

away

from the natural orifices, then it

is likely that this is the site of a wound.

-

The presence of

drugs can be determined using insect evidence.

It is even

possible to determine the type of

drug present.

-

Insects can be

used to place a suspect at the scene of a crime.

-

Civil cases also

sometimes use insect evidence.

-

Some insects will

colonize wounds or unclean areas on a living person. This is

called cutaneous myiasis. In these types of cases the victim is still

living, but

maggot infested. A forensic entomologist can tell when the

wound or neglect/

abuse occurred. These kinds of infestations occur

particularly in young

children and senior adults.

-

Insects can

determine the point of origin in many illegal drug caches or even the

Path of stolen automobiles as they

get handed off in organized car rings.

Forensic Entomology Cases

INSECT TIME OF DEATH

ESTIMATE:

The body of

a 37-year old man was found by joggers in a swamp on one of

SKULL ANALYSIS:

A skull

found in the spring of 1985 in

UNDERWATER INSECTS:

During the

summer in

The victim’s husband claimed that he had last seen his wife in June. He told the police that he and his wife had an argument and she had driven away while still angry. It had been a foggy night and perhaps she had lost her way and accidentally plunged into the river. But cocoons found on the fender of the car proved him to be lying. In the winter, black flies are in their larval stage, and in the spring they go underwater in a river or stream and weave cocoons. They then attach themselves to rocks and other large hard surfaces such as a submerged car. Because of the cocoons, the forensic entomologist determined that the car had to have been in the water no later than April or May but not as late as June. The husband had killed his wife and dumped her car and body into the river in the spring, long before he reported her missing in June. The husband was convicted and sent to prison.

ENTOMOLOGY TRIVIA:

A female blowfly can lay 600 eggs in one day.

Adipocere, or grave wax as it is commonly referred to, is unlikely to form if a body is readily accessible to insects.

The blowfly will mature into an adult in about 20 days, based on an average daily temperature of 760 F or 230 C. A cheese skipper will mature into an adult in about 40 days and a lesser housefly in about 50 days based on the average temperatures previously listed.

Forensic

Entomology Web Sites to Explore

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forensic_entomology

https://www.crimesceneinvestigatoredu.org/forensic-entomologist/

https://www.forensicscolleges.com/blog/htb/how-to-become-forensic-entomologist

An

Experiment on Forensic Entomology

During this

experiment you will observe and collect evidence about the arrival of insects on

a corpse. This is a simulated activity

as you will not be using a corpse, human or animal. This

experiment works best if the outside temperatures are mild or warmer. If it is fall when you complete this unit and

temperatures are mild, you may want to do the experiment now. If it is winter, you may want to wait until

warmer spring weather is here. Since our

weather is seasonal, there will be very little or no insect activity during the

winter months. You will share the

results of this experiment on the final exam.

This experiment will take about three weeks to complete. During this experiment you will be using three simulations that would represent the type of insect activity you might see on a human corpse. The liver submerged in water is a simulation of a body that is submerged in water. The liver sample wrapped in plastic wrap is a simulation of a corpse wrapped tightly and securely in plastic or some other sealing wrap. The last sample is a simulation of an uncovered corpse being exposed to various environmental factors such as temperature, weather, etc.

|

FORENSIC

SCIENCE KIT UNIT 09 |

|

- 3 pieces of raw beef liver |

|

- 2 Styrofoam plates |

|

- dishpan filled with water |

|

- plastic wrap |

|

- magnifying glass |

|

- tweezers |

|

- thermometer |

|

- safety goggles/glasses |

|

- exam gloves |

|

- notebook and pencil |

Procedure:

1. Place one piece of liver in a water-filled dishpan outdoors. Make sure the sample

is located where animals cannot disturb it but is accessible to insect activity.

2. Wrap a second piece of liver securely in plastic wrap. Place it on the Styrofoam

plate and put it in a location where animals cannot gain access to it.

3. Take the last piece of raw beef liver and place it uncovered on the Styrofoam plate.

Set this sample in a location where it is accessible to insect activity but out of the

reach of animals.

4. Each day in your notebook you are to observe and record the following information:

-

temperature of the air and water

- any observation of insect

activity (be specific)

- weather conditions (be specific)

- time of day

5. Once you have noted any type of insect activity in any of the three samples, note

any observations, being specific in your written explanation. Pay close attention

to the arrival of each species of insect, the stages of the life cycle, and draw

examples of what you observe. Use the tweezers to take samples at various

stages of development and look at the specimens with the magnifying glass.

Remember to wear exam gloves when working with live specimens. If you have

access to a microscope, this would be a good opportunity to get a close look at

these specimens.

At the end of the experiment, make sure you dispose of the liver samples appropriately.

You will be sharing the results of this experiment on the final exam. Make sure that your notes are specific so that when you refer back to them they are clear and precise. As you are completing the experiment, keep the following questions in mind:

|

- Which sample had more insects living on or in the liver? Why? |

|

- Were your samples placed in the sun or the shade? Did it make a difference with your results? |

|

- Describe the larvae size and shape. Describe any differences. |

|

- Based on your observations, which species of insects arrived first, next and last? |

|

- Be able to draw the life cycle of at least one species of insect. |

|

- Over the course of the experiment, did you notice any changes in the color, shape, size, or smell of the liver in each sample? |

|

- Where on the liver did you first notice that the eggs were laid? |

The Future of Forensic Entomology

Forensic entomology is developing at a rapid pace. This science can now determine whether or not a victim was on drugs by testing the insects that fed on the decomposing body. Eventually scientists will be able to test the bug splats on a suspect’s car or the sand flies stuck to a suspect’s grillwork and use this information to determine who was at the scene of the crime. Entomologists are being called upon with increasing frequency to apply their knowledge and expertise to criminal and civil proceedings. They are also recognized members of forensic laboratories and medical/legal investigation teams.

Forensic

Careers to Explore

|

forensic entomologist |

forensic meteorologist |

|

medical examiner |

aquatic forensic entomologist |

|

cultural entomologist |

|

Conclusion

In conclusion, insects are evidence! Forensic entomology is a useful method for determining elapsed time since death, and is now being used to answer other questions involving insects. A knowledge of insects and the methods of collecting, handling, and preserving the evidence is crucial to aiding in the solving of a crime.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()