TAXING AND SPENDING

Unit

Overview

Although

no one likes to pay them, taxes are necessary because they generate the money

to fund the goods and services that Americans have come to expect from their

government.† National defense, education,

highways, help for people in need and law enforcement are just a few things

that our tax dollars provide.† Like

households, the President and Congress share the responsibility for preparing a

budget to allocate the nationís financial resources.† This involves planning, analysis and, like

all economic decisions, trade-offs.† Letís

see how it all happens.

The

Power to Tax

To

acquire the money that they need to operate, governments require citizens to

pay taxes.† Income from taxes and other non-tax sources,

such as loans or government-owned enterprises, is called revenue.† Without revenue,

government would not be able to provide the services that Americans have come

to expect.† These include national

defense, education, infrastructure and help for those in need.† The Founding Fathers intensely debated the

wisdom of giving the federal government the authority to tax.† For this reason, the Constitution sets very

specific limits on this power.† It cannot

be used to collect money that goes to individual interests, and federal taxes

must be the same in every state.† The

Constitution also prohibits certain types of taxes.† For example, since it violates the freedom of

religion guaranteed by the First Amendment, Congress cannot tax church

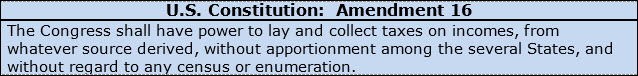

services.† The Constitution, however, can

also be amended.† In 1913, the Sixteenth Amendment legalized the

collection of federal income tax, which had been declared unconstitutional by

the Supreme Court.†

Although

no one really wants to pay taxes, we will always need them.† For this reason, it is important that taxes

be equitable, reasonably simple to understand and easy to collect.† Citizens and businesses should be able to

prepare their own tax forms and to pay what they owe on a regular

schedule.† At the same time, government

officials need to collect taxes without spending too much time and money.† A tax must generate enough revenue to make

the process worthwhile.† Tax payers want

a system that is fair and avoids loopholes.†

These are exceptions that permit some people to pay less than others.

![]() Go to Questions 1

and 2.

Go to Questions 1

and 2.

Tax

Structures

When

adding new taxes, federal, state and local governments make two important

decisions:† exactly what is going to be taxed

and how the tax is going to be structured.†

The property, income, good or service that is taxed is referred to as

the tax base.† After establishing a tax

base, governments must then choose the best way to structure the tax.† Economists divide tax structures into three

categories:† proportional, progressive

and regressive.† As with all decisions,

each tax structure comes with benefits and trade-offs.

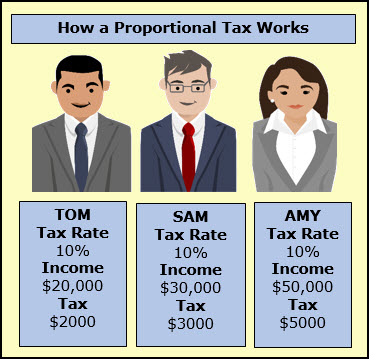

A proportional tax, sometimes called a flat tax, requires everyone to pay the

same percentage regardless of their income.†

The more money an individual makes, the more he or she pays in

proportional tax. For example, aside from federal income tax, some towns and

cities also collect local income taxes from their residents.† Unlike federal income tax, everyone usually

pays the same percentage.† Based on a tax

rate of 2%, an architect with an income of $125,000 annually pays $2500.† A nurseís aide, who earns $30,000 a year,

also pays 2% for a total of $600.† Proportional

taxes have several advantages.† They are

simple to understand and easy to collect.†

On the other hand, opponents argue that proportional taxes are unfair

because they demand more sacrifices from lower-income households that already

spend most of their earnings on necessities.

Because

it is based on a percentage that may increase or decrease depending on changes

in income, a progressive tax

structure is more complicated than a proportional system and requires the

supervision of government agencies, such as the Internal Revenue Service.† At

the same time, progressive taxes generally produce the most revenue.† Federal income tax is one example of a

progressively structured tax.† Under this

system, people with large incomes pay more, while those with small incomes pay

little or nothing.† The federal income

tax code consists of several levels called brackets.† A tax payer may pay several different rates

depending on his or her earnings.† In

other words, the government divides taxable incomes into pieces, and each piece

is taxed at a corresponding rate.

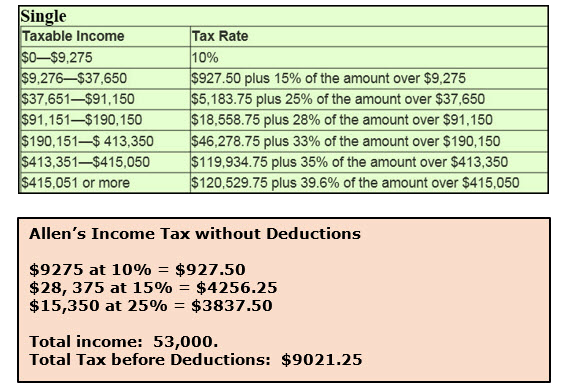

Letís

see how it all works by looking at a single taxpayer.† Allen is an electrical technician and earns $53,000

annually.† At first glance, you may think

that Allen simply has to pay 25% of $53,000.†

Fortunately for our taxpayer, this is not the case.† Allen pays 10% on $9,275 of his

earnings.† Moving to the next bracket, he

owes 15% of $28,375.† This leaves $15,350

for the third bracket at 25%.† The

graphic below illustrates Allenís tax calculations.

Governments

also add to their revenue by collecting taxes based on the regressive structure.† Under a regressive

tax, the percentage of income paid in taxes goes down when income

increases.† This format is often

criticized because it imposes a greater burden on low-income households.† State sales tax qualifies as a regressive tax.† Letís say someone who earns $20,000 annually spends

$7,200 on clothing and food.† At the same

time, a person making $200,000 spends $20,000 on the same essentials.† If the state sales tax is 5%, the individual

earning $20,000 spends almost 2% of his or her annual income on state sales

tax.† Although the person earning

$200,000 spends more money on food and clothing, the state sales tax on these

items adds up to .5% of his or her total income.† For this reason, opponents of the regressive

tax structure argue that these taxes are unfair.† At the same time, they are easy to understand

and simple to collect.† Therefore, they

continue to be a valuable source of revenue.†

![]() Go to Questions 3

through 8.

Go to Questions 3

through 8.

Collecting

Taxes

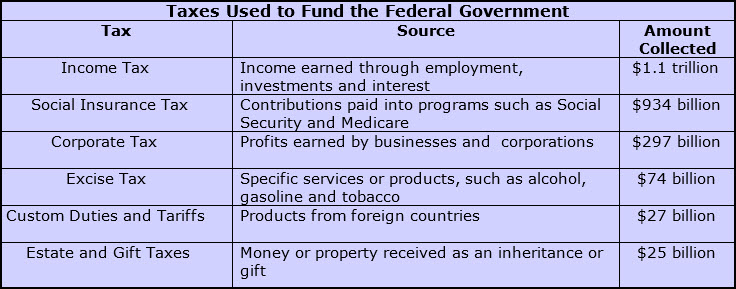

The

federal government has several major sources of tax revenue.† You can see how they contribute to the

nationís financial status in the table below.†

Although the goal of taxes is to create operating money, sometimes the

federal government also uses them to discourage the public from buying harmful

products.† Federal taxes on tobacco and

alcohol, often referred to as sin taxes,

fall into this category.† In these

cases, taxes not only provide money for goods and services but also serve as

incentives to change behavior.

Individual

income taxes are currently the countryís main source of revenue.† Because the amount that each person owes is

determined annually, the government could collect this tax in one lump sum at

the end of the year.† It is likely,

however, that this would create problems for taxpayers and government.† A single, annual payment from everyone at

once would make it difficult for the government to cover expenses, such as

rent, salaries, supplies and services, throughout the year.† Taxpayers, too, might have trouble budgeting

the money for one, large tax bill.† For

these reasons, employers are responsible for collecting taxes on a pay-as-you-earn

system.

Rally to Protest a

Tax Increase

Under

the pay-as-you-earn system,

employers withhold, or take out,

payments from workersí salaries before they receive them.† Then, they forward this money to the federal

government.† At the end of the year,

every employee receives a W-2 form

from his or her employer.† This report

shows the total amount of income tax paid during the year.† Workers use this information to complete tax

return forms that determine whether the amount withheld covers the tax

owed.† If the total collected by the

employer is lower than the actual amount due, the worker pays the difference.† On the other hand, if the total collected by

the employer is higher than the actual amount due, the worker receives a refund

from the federal government.† Midnight on

April 15 (or the first business day

after April 15) is the deadline for submitting tax returns for the previous

year to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

In

addition to income taxes, employers also deduct funds for Social Security and

Medicare, two well-known federal programs.†

Social Security, launched in

1935 in response to hardships encountered during the Great Depression, was

established as a retirement fund that provided pensions for older

Americans.† Today, the fund also pays

benefits to disabled workers and the surviving family members of wage

earners.† Medicare is the countryís national health insurance program.† It helps people over sixty-five pay for

hospital care and medical services.† It

also assists people who suffer from certain diseases and disabilities.†

![]() Go to Questions 9

through 13.

Go to Questions 9

through 13.

Setting

up the Federal Budget

Just

as households plan the best way to utilize their financial resources, Congress

and the President share the responsibility for establishing the federal budget.† This plan lists the nationís expected income

and shows exactly how the money will be spent.†

The federal government prepares a new budget for each fiscal year.† A fiscal

year is a twelve-month period that does not necessarily follow the

traditional January-through-December format.†

Usually, the federal governmentís fiscal year runs from October 1

through September 30.†

The

process begins with the offices and agencies funded by the federal

government.† Each one prepares a detailed

estimate of the money needed to operate during the upcoming fiscal year.† The Office

of Management and Budget (OMB), an

agency within the executive branch, reviews these proposals and works with the

Presidentís staff to combine them into a single document.† The President presents this spending plan to

Congress in January or February. At this point, the budget is nothing more than

a request.† Congress must approve the

funds to make it a reality.

For

the next few months, Congress studies, debates and modifies the Presidentís

proposed budget.† Committees in the House

of Representatives and the Senate hold hearings and listen as agency officials

explain their funding requests.† The Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

assists in the process by collecting additional statistics concerning the

economy.† Before the end of the fiscal

year, Congress must pass the revised budget and a series of appropriation, or

spending, bills to pay for it. Once the President signs the appropriation bills, the budget becomes

the official spending plan for the new fiscal year beginning on October 1.† The President also has the option of vetoing

these bills.†

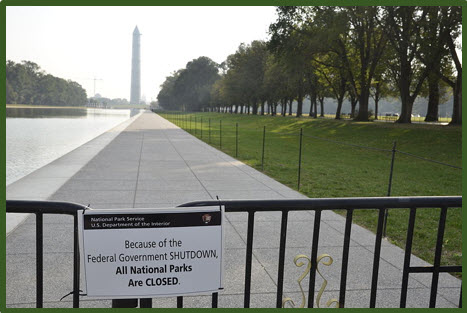

Shutdown

Barricades at the Washington Monument:†

2013

If

the budget is not finalized by September 30, Congress approves stop-gap funding.† This emergency legislation keeps the

government running temporarily.† If the

President refuses to sign this measure, the government stops functioning.† For example, in 2013, the government

experienced a sixteen-day shutdown. For over two weeks, only essential

services, such as the military, remained operational.† The news clips listed below describe the

events leading up to the federal shutdown.† Nearly 800,000 federal employees experienced

lay-offs; others were required to report for work but did not know when they

would receive their next paychecks.†

National parks and monuments closed, and some benefit payments were

delayed.† Congress and President Obama

eventually reached a compromise and agreed on a new bill to end the crisis.

![]() †

Government Budget Standoff †††

†

Government Budget Standoff †††

![]() † Go to Questions 14 through 16.

† Go to Questions 14 through 16.

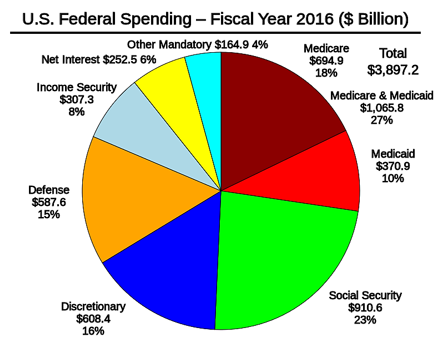

Where

Does All the Money Go?

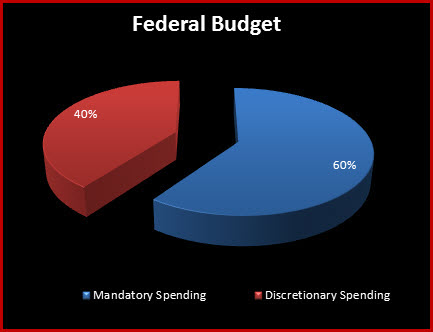

Federal

spending is divided into two major categories, mandatory spending and

discretionary spending.† Mandatory spending consists of payments

that the government is required by law to make.†

Along with interest fees on the national debt, this category includes a

number of entitlement programs, such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and

the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP).† Entitlement

programs pay benefits to U.S. citizens who meet certain eligibility

requirements established by law. In other words, people qualify for, or are

entitled to, these benefits because they meet certain legal standards. Unlike

other areas of the federal budget, Congress does not annually approve dollar

amounts to fund these programs. It may, however, pass new legislation that

changes eligibility criteria or benefit formulas.†

The

remaining items in the federal budget make up what is known as discretionary spending.† Discretionary spending covers defense,

education, student loans, scientific research, national parks, disasters aid

and many other federal programs.† To fund

these areas of the budget, Congress passes appropriation bills with specific

dollar amounts attached.† This means that

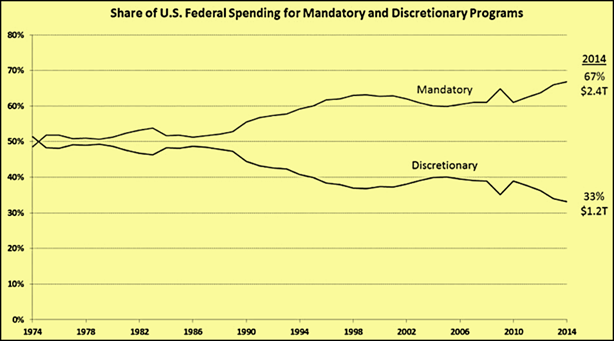

Congress must make choices that result in trade-offs.† Before the Great Depression, almost all

government spending was discretionary.†

However, the creation of Social Security in 1935 and Medicare in 1965

changed how the federal government spent its money.† Today, almost 70% of the federal budget is

devoted to mandatory spending.† The graph

below shows the changes in mandatory and discretionary spending over the course

of several decades.

![]() Go to Questions 17

through 19.

Go to Questions 17

through 19.

Deficit

and Surplus

When

federal spending equals federal revenue for a given fiscal year, the

governmentís budget is balanced.† The same amount of money is flowing into the

Treasury as is flowing out of the Treasury.†

In reality, this almost never happens.†

Most of the time, the government operates at a deficit or a

surplus.† When a fiscal yearís revenue is

greater than its expenses, a budget

surplus occurs.† During the

mid-1990s, tax increases, a strong economy and low unemployment resulted in

several fiscal years of surpluses.† These

favorable circumstances did not last long.†

The stock market boom ended, tax cuts reduced the amount of money

collected and terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 disrupted the

economy.† All of these factors added up

to a series of fiscal years with budget deficits.

A budget deficit is the result of the

government spending more than it takes in. †In this situation, printing more money is an

option, but this causes inflation and lowers the value of the countryís

currency.† Therefore, the government

usually chooses to borrow the money to make up the shortfall.† This action has its advantages.† Borrowing money permits the government to

undertake projects it could not otherwise afford.† It also allows government to produce more

goods and services.† Unfortunately, each

fiscal year of budget deficits increases the total amount of money owed.† This accumulates and grows into what is

called the national debt.† The video listed

below explains the history of the national debt.† It also discusses its pros and cons.

![]() † The Historic Struggle with the National Debt

† The Historic Struggle with the National Debt

![]() Go to Questions 20

through 22.

Go to Questions 20

through 22.

Whatís

next?

When

planning the federal budget, Congress and the President deal with the basic

economic problem of allocating scarce resources.† Countries, like individuals, cannot produce

all the goods and services they need or want.†

One way that nations deal with this problem is through trade.† Is it cheaper for a country to import certain

products rather than manufacture them?†

Should a country specialize in a few goods that it can export at a

profit?† Before moving on to answer these

questions in the next unit, review the terms found in Unit 14; then, answer

Questions 23 through 32.

![]() Go to Questions 23

through 32.

Go to Questions 23

through 32.

† †