ALL ABOUT THE MONEY

¸

Paper Money from

Various Countries

Unit

Overview

Because

we cannot get the things we need and want without it, money is an essential

part of our daily lives. If asked, most

of us would define it as the bills in our wallets or as what we receive when we

cash our paychecks. It should come as no

surprise that economists have their own language when it comes to defining

money. In this unit, you will view money

from an economist’s perspective. What

gives money value? What are its

characteristics and functions? How does

it circulate throughout the economy?

Let’s see how it all works.

How an

Economist Defines Money

Almost

all societies have established a form of money to simplify financial

transactions. An economist defines money

as anything that provides a medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store

of value. If something is going to work

as money, it must be accepted by all parties as payment for goods and

services. In other words, an object has

to function as a medium of exchange

to be considered money. Workers must

agree to accept it in exchange for their labor, and merchants must agree to

accept it as payment for goods. Throughout

history, a wide variety of materials, such as gold dust, rice, salt and cattle,

have been used as a medium of exchange.

For

an article to be regarded as money, it must serve as a unit of account. This is

also referred to as measure of value.

This function assists consumers in comparing the values of goods and

services. For example, let’s say you see

a pair of running shoes on sale in a shop for $45.00. Because the price is expressed the same way

in every store in the United States, you can easily compare the cost of the

shoes if you see the same item offered elsewhere. Units of account provide a convenient and

easily understood method of identifying and communicating value. In the United States, dollars and cents operate

as units of account, but other countries use their own money for this purpose. For the Russians, the ruble is a unit of

account, while Mexicans use the peso in a similar way.

Price in Dollars and Cents Helps Buyers

to Compare Value

To

be considered money, an item must serve as a store of value. This means

that money maintains its value whether you spend it today or tomorrow. If you keep your money in your purse or in

the bank, it will still be a unit of account and recognized as a medium of

exchange for the same amount months or years from now. Money works well in this capacity with one

important exception. Sometimes economies

experience a quick rise in prices, or inflation. In this case, purchasing power declines. The running shoes that were once $45.00 are

now $55.00, and consumers are able to purchase less with their stored

funds. When an economy experiences

inflation, money does not function well as a store of value.

![]() Go to Questions 1

through 4.

Go to Questions 1

through 4.

Characteristics

of Money

Along

with having specific functions, objects used as money need to have certain

characteristics if they are going to serve society successfully. They must be durable, divisible, uniform,

portable, limited in supply and acceptable.

Because it is used over and over again, money must withstand physical

wear and tear. After all, it cannot be

trusted as a store of value if it is not durable. Coins are some of the longest-lasting

examples. In fact, Greek and Roman

coins, made over two thousand years ago, are highly prized by collectors

today. Because American paper money has

a high degree of cloth, or rag, content, it withstands the rigors of

circulation and can be easily replaced if it does not.

To

serve a practical purpose, buyers and sellers should be able to divide money

into smaller units simply. In the 1700s,

Spanish coins, called doubloons, had

lines etched on them so that they could be broken apart easily. Because these coins were designed to be divisible, Spaniards referred to them

as pieces of eight. Today, instead of

tearing dollars into smaller pieces, Americans address this issue by relying on

coins and paper bills that come in a variety of denominations. In other words, we do not need to cut up

twenty-dollar bills because we have ones, fives and tens. At the same time, money should also be uniform. Everyone must be able to count and to measure

it accurately. Each dollar is obliged to

buy the same amount of a good or a service.

What would happen if the U.S. economy adopted oak leaves as money? Because not all oak leaves are the same size,

consumers might spend one on one day and three on another day to purchase the

same product. This would probably result

in frequent arguments between buyers and sellers.

An Example of the Portability of Paper

Money and Coins

Portability

is one of the most necessary and practical characteristics of money. People first exchanged goods and services

through barter. This refers to the direct transfer of one

product for another. Although it is

still currently used in some parts of the world, specialized economies find the

practice difficult and time-consuming.

To conduct business efficiently, buyers and sellers need to take their

money with them. In other words, money

is more useful when it is portable. Since coins and paper bills are small and

easily carried, they have a distinct advantage over bartered goods. Everyone in the economy needs to be able to

trade the objects serving as money for goods and services. This means that money must be acceptable across the country. In the United States, store owners accept

American money because they can spend it anywhere to buy things that they want

our need. At the same time, Americans

expect that businesses will continue to honor paper money when they make

purchases.

Like

almost everything else, money loses its value when there is too much or too

little of it. In colonial Virginia, for

example, tobacco functioned as money.

This worked reasonably well until more farmers started to grow it. As the supply of tobacco increased, the price

dropped from thirty-six cents per pound to one cent per pound. This made “tobacco money” worthless. To avoid situations like this, the U.S.

government controls the amount of money in circulation through the Federal

Reserve. This gives money value because

the supply is limited. The Federal Reserve keeps enough money in

circulation to encourage economic growth.

It can also decrease the amount money in circulation to avoid inflation.

![]() Go to Questions 5 through 9.

Go to Questions 5 through 9.

What

Makes Money Valuable?

Although

paper bills are practical objects, they have little value of their own. In reality, they are only pieces of

paper. What makes the objects used as

money special, and why do we regard them as valuable? There are several possible answers because

there are different kinds of money.

Economists divide money into three types: commodity money, representative money and

fiat money.

Ø Commodity money:

Commodity money consists of objects that are not only useful as money

but also have value in their own right.

You read earlier that tobacco was used as money in colonial Virginia. However, it could also be traded as a

product. Salt is another example. Although it, too, served as money, it also

had value as a seasoning and as a preservative.

Commodity money has the advantage of being functional in other ways when

it is not being used as money. However,

it also has drawbacks. Commodity money

is often not durable, divisible or portable.

As societies grow and become more sophisticated, they usually require a

more convenient system for the exchange of goods and services.

Examples of Items Used as Commodity

Money: Arrow heads, Rice and Gold Dust

Ø Representative money:

Unlike

commodity money, representative money has no value itself, but it stands for

something that does. In the 1800s, the

United States government began to issue gold and silver certificates. These pieces of paper were backed by actual

gold and silver, and holders could redeem them for an equal amount of these precious

metals at a local bank. In 1900,

Congress passed the Gold Standard Act.

This law fixed the price of gold at $20.67 and obligated the federal

government to exchange dollars for gold at that rate. Americans felt more secure knowing that their

money represented gold in the National Treasury. The 1930s, however, ushered in uncertainty,

unemployment and a record number of bank failures. Americans no longer trusted banks to keep

their money safe and redeemed cash for gold.

The federal government feared that it did not have enough reserves to

meet the public’s demands. In 1933,

President Franklin Roosevelt declared a national emergency, and America went

off the gold standard. U.S. money was no

longer representative.

U.S. Gold Certificate

Ø Fiat money:

American dollars and coins today are classified as fiat money. A fiat

is an order or a decree. Also referred

to as legal tender, fiat money has

value because the federal government says that it does. The Federal Reserve

monitors the supply of fiat money carefully so that it remains limited and,

therefore, valuable.

![]() Go to Questions 10

through 13.

Go to Questions 10

through 13.

Money

and the Circular Flow

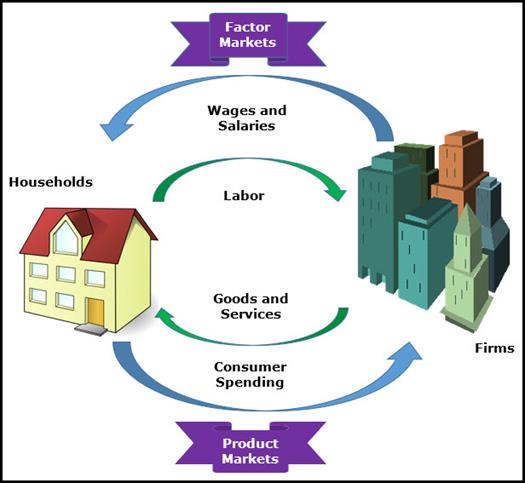

In a

market economy, households, which

are made up of individuals living in the same residences, and firms, or businesses, exchange

resources, products and money in the marketplace. Economists use diagrams like the one below to

illustrate this process. Follow the

circle created by the blue arrows.

Households spend money to purchase goods and services from firms. Firms, in turn, use this money to pay

households for the resources that they need to manufacture their products. For example, companies hire workers to whom

they pay salaries, wages and benefits. This

outer circle is known as the monetary

flow. On the other hand, the green

arrows of the inner circle form the physical

flow, or the flow of resources. Households

supply firms with labor and capital, while firms supply households with goods

and services.

Let’s

look at the diagram another way. Focus

on the upper part of the graphic. It

represents the markets where resources are bought and sold. These are called factor markets because

businesses buy the factors of production in them. The lower portion of the diagram shows

households and firms interacting in product

markets. Here, households buy goods and services produced by firms. Once individuals receive their income in the

factor market, they spend it in the product market. Firms then use this money to produce more

goods and services. This creates a

continuous flow, or cycle.

![]() Go to Questions 14

through 17.

Go to Questions 14

through 17.

The

Future of Money

In

this unit, you have read about the functions and characteristics of money. Although paper bills and coins have their

advantages, some analysts argue that they will soon be obsolete. Will cash as we know it cease to exist in the

near future? Would it be better to replace

it with electronic money or smart cards?

Is cyber money a serious threat to our privacy? Read the opposing points of view quoted in

the graphic below.

|

The Pros and Cons of Eliminating

Paper Bills and Coins |

|

|

Bring on the Cashless Future |

The Hubris of Eliminating Cash |

|

Cash had a pretty good

run for 4,000 years or so. These days, though, notes and coins increasingly

seem outdated. They're dirty and dangerous, unwieldy and expensive,

antiquated and so very analog. Sensing

this dissatisfaction, entrepreneurs have introduced hundreds of digital

currencies. This is a welcome

trend. In theory, digital legal tender could combine the inventiveness of

private virtual currencies with the stability of a government mint. Most obviously, such a system would make

moving money easier. Properly designed, a digital fiat currency could move

seamlessly across otherwise incompatible payment networks, making

transactions faster and cheaper. It would be of particular use to the poor,

who could pay bills or accept payments online without need of a bank account,

or make remittances without getting gouged. For governments and

their taxpayers, potential advantages abound. Issuing digital currency would

be cheaper than printing bills and minting coins. It could improve

statistical indicators, such as inflation and gross domestic product.

Traceable transactions could help inhibit terrorist financing, money

laundering, fraud, tax evasion and corruption. Editorial Board, Bloomberg View January, 2016 |

An end to cash would

mean that every financial transaction is exposed to a third party. Protecting

one's privacy from the prying eyes of the government isn't the only concern

either. Cashlessness has

implications for people who want to hide their medical conditions. It has implications

for people who don't want their credit score dinged when, say, they make a

purchase at Walmart. Beyond a certain threshold I'd alert my wife to a

purchase, but do I want her knowing exactly what I spend on my insatiable

avocado habit? Thank goodness for cash. Cash should remain,

always and everywhere, because it allows, private, peer-to-peer transactions.

In doing so, it decentralizes power in society (as well as adding a layer of

resilience to the financial system—a diversification between the physical and

virtual). Having stuff in society that elites can't completely control is a

good thing. Keeping a large swath of the economy away from Big Finance and

Big Data is a good thing. Finally, people like cash; we shouldn't let the

elites take it away. Conor Friedersdoft, The Atlantic June, 2014 |

![]() Go to Questions 18 through 23.

Go to Questions 18 through 23.

What’s

next?

The

circular flow model shows that households sell their talents and skills in

return for salaries and wages. They

sometimes also provide financial capital for businesses in the form of

investments. Investments often earn

profits and grow the nation’s wealth, but they always come with varying amounts

of risk. Before moving on to explore

this topic in the next unit, review the terms found in Unit 9; then, complete

Questions 24 through 33.

![]() Go to Questions 24

through 33.

Go to Questions 24

through 33.