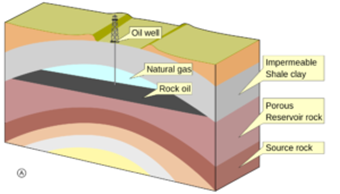

Figure 1. Conventional Reservoir

CONVENTIONAL VS. UNCONVENTIONAL RESERVOIRS

When oil and natural gas have migrated upwards, have been stopped by a less permeable rock like shale, and are trapped in a relatively porous and permeable formation like sandstone, we refer to this as a conventional reservoir. In the picture to the right, the oil and natural gas are being shown trapped in a "porous reservoir" with "source rock" (shale) below it and "impermeable shale clay" above it. Please note that the oil and natural gas are located inside the "porous reservoir rock" layer in the image. Conventional reservoirs typically have decent permeability, which refers to how easily hydrocarbons can flow through the porous rock. This dictates the types of treatments that must be done to produce these wells once they are drilled. It is not uncommon for a conventional well to be capable of flowing economically once it is drilled, but many are still stimulated in some way to promote an easier flow of the hydrocarbons into the well. Many conventional wells have been treated with acid and some have been hydraulically fractured [also known as fracing (or more commonly, "fracking")]. Also, note that a vast majority of these wells are vertical wells (as shown in the picture above and below).

Figure 1. Conventional Reservoir

Conventional reservoirs are where the oilfield got its start and have been produced since the 1800s. Back when exploration and drilling began, many wells struck oil in very shallow sandstones - some even as shallow as 100 feet! As technology improved and demand increased, drillers drilled deeper and began finding even more prolific oil and gas bearing formations. Then, it wasn't long until they began trying to "stimulate" the well in order to get the oil out quicker. The most common method of choice became known as "shooting the well" with nitroglycerin, a highly explosive liquid which would be lowered into the well and detonated. Thankfully, we have long since moved onto safer and more effective treatments which will be examined in this course.

Figure 2. Typical conventional well as seen at the surface.

A good example of a conventional well is that of a vertical Clinton Sandstone well with a small pumpjack at the surface. In this example, Clinton Sandstone is the formation that it was drilled into and is producing from. Conventional wells are typically what we see in a hayfield, alongside the road, in your backyard, etc. Conventional wells are found all over the place. There are literally thousands of these just in Ohio. There is also a large number of conventional plays all over the U.S. - too many to count! A good example picture of a conventional well can be seen to the right.

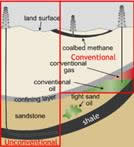

Unconventional reservoirs differ in the sense that the rock we produce from is both the source of the hydrocarbons and is also where the hydrocarbons are trapped. They have not migrated. These reservoirs are often shale rock themselves and have very poor permeability. This means that the hydrocarbons within are not able to escape very easily. Hence, they are still there. Because there is little flow within the formation, the hydrocarbons do not easily flow into a well either. Thus, to make these wells economic, more extensive development must occur. Oftentimes, horizontal wells are drilled into these formations in order to maximize contact with the formation. (See image below to visualize the difference.) Furthermore, these wells are more extensively stimulated (usually fraced) than conventional wells. Although the procedure of fracing an unconventional reservoir is very similar to that of a conventional reservoir, the difference is in the scale. We will discuss this later on in this course. In the end, once the well has been drilled and fraced, it will be much more productive than if it was a vertical well, and that is what justifies the enormous financial investment that these wells require to drill, frac, and begin producing. A good example of an unconventional well is a horizontal Marcellus Shale well. These wells are typically located on a large pad with multiple other wellheads, numerous tanks, and other production equipment. In this example, the Marcellus Shale is the formation the well is drilled into and producing from. Other common unconventional plays in the U.S. are the Utica Shale, Eagle Ford Shale, Haynesville Shale, and many others.

Figure 3. Wellpad with 4 Utica Shale wells and associated production equipment.

You might be wondering why you should care about the difference. The answer is mainly so that you can designate the difference between the two. A vast majority of the U.S. onshore drilling is that of unconventional wells. This is important to realize because unconventional wells typically come with a much larger scale in terms of their operations and what it takes to drill, complete, and produce those wells. Thus, the majority of this course will focus on the unconventionals.

Figure 4. Conventional vs. Unconventional