THE SPREAD OF THE

PROTESTANT REFORMATION

THE SPREAD OF THE

PROTESTANT REFORMATION

Henry VIII:

King of England

Unit

Overview

The

Protestant Reformation, which had caught fire in Germany, spread across

Europe. Reformers, such as John Calvin

and John Knox, combined the ideas of Martin Luther with their own

interpretation of Christianity. Henry

VIII refused to accept the pope’s authority and set the stage for religious

change in England. This resulted in new

churches and different forms of worship.

It also led to major disagreements among European Christians. At the same time, the Roman Catholic Church

launched the Catholic Reformation in an attempt to slow the advancement of

Protestantism. Let’s see how it all

happened.

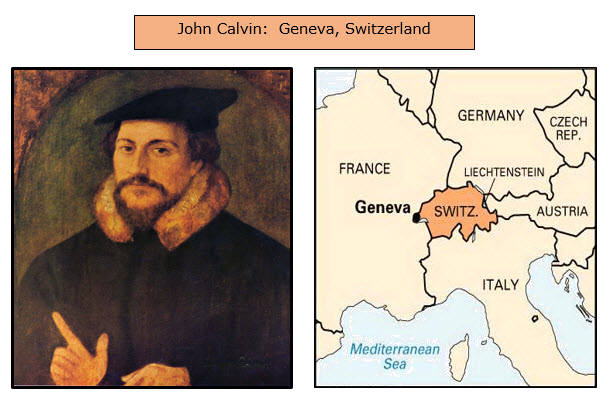

John

Calvin and the New Generation of Reformers

By

1520, the concept of religious change had swept over Europe, and a new

generation of reformers built on the ideas of Martin Luther. John

Calvin, a native of France, was one of the most influential. Trained as a Catholic priest and as a lawyer,

Calvin published his book Institutes of the Christian Religion

in 1536. It explained his beliefs and

offered advice on how to set up a Protestant church. This book became very popular and was widely

read by Protestants all over Europe. The

citizens of Geneva, Switzerland were

so impressed by his writings that they asked John Calvin to lead their

community. Calvin agreed and established

a theocracy, a form of government

run by church leaders. The Calvinists

stressed the importance of hard work, self-discipline, saving money and

honesty. People came from all over

Europe to visit Geneva and to see first-hand the effects of Calvinism.

The

ideas of John Calvin spread as Protestants returned home and shared their observations. New Christian sects, such as the Anabaptists,

took root in communities throughout Europe.

The concepts that inspired reformers, however, threatened Roman

Catholics, and armed conflict over religious issues became increasingly

common. In Scotland, a Calvinist

supporter named John Knox led a

religious rebellion. Scottish

Protestants overthrew their Catholic queen and set up the Scottish Presbyterian

Church. At the same time, Calvinists

called Huguenots battled with

Catholics in France. Wars continued in the

German states between Catholics and Protestants and between Calvinists and

Lutherans. England, too, would

experience a break with the Roman Catholic Church. In this case, however, it happened more for

political and personal reasons rather than religious ones.

Henry

VIII and the Church of England

When

Henry VIII, king of England, first

heard of the ideas expressed by Martin Luther, he wrote a pamphlet that

emphasized just how wrong Luther was. Pope Leo X was so impressed with the

king’s efforts that he awarded him the title Defender of the Faith. In

1527, Henry’s personal life and the issue of a male error transformed his

relationship with the Roman Catholic Church.

As a young prince, Henry had entered into an arranged marriage with Catherine from Aragon, a province in

Spain. Once he became king, Henry VIII

was convinced that a stable government depended on a male heir or a son to

inherit the throne. Although he and Catherine

had been married for eighteen years, the queen’s only surviving child was a

girl called Mary Tudor.

Windsor

Castle: Rumored to Be Haunted by the

Ghost of Henry VIII

Since

it seemed unlikely that he would have a son if he remained married to Catherine,

Henry wanted to divorce her and to marry Anne

Boleyn. Since the laws of the

Catholic Church did not permit divorce, the king asked Pope Clement VII for an annulment. This would cancel his marriage to Catherine

and would give Henry the freedom to marry Anne.

Popes had granted these types of requests for royal families in the past

so Henry assumed it would not be a problem.

In this instance and at this time, it was. Catherine’s nephew was none other than Holy

Roman Emperor Charles V, who had

agreed with Rome’s condemnation of Martin Luther. Not wanting to offend his ally, the pope

refused to okay the annulment.

Henry

VIII was determined to divorce Catherine in spite of the pope’s ruling. He called a meeting of Parliament and asked

the assembly to pass several new laws concerning the Church. The Act

of Supremacy, which went into effect in 1534, officially made Henry, not

the pope, the head of the Church of England.

Anyone who refused to accept this law was executed for treason. The king appointed his friend Thomas Cranmer as the Archbishop of

Canterbury. The new archbishop gave

Henry his annulment and permission to marry Anne Boleyn. Much to Henry’s disappointment, she did not

produce a son but one daughter named Elizabeth.

Eventually, Henry VIII married four more times. Jane

Seymour, his third wife, gave birth to Henry’s only son, Edward.

To

gain support for his break with Rome, Henry closed all of England’s monasteries

and seized their lands. Since

monasteries owned almost one-third of all English property, this undertaking

increased his royal power and the royal treasury. Henry sold large amounts of

this land to the nobles and members of the middle class. As a result, the new landowners stood to lose

their property if England returned to the Catholic Church. This gave Henry some solid support for

England’s Protestant Reformation. In most

ways, however, Henry continued to be more of a Catholic than a Protestant. Although he permitted the scripture to be

read in English, he insisted that services and celebrations remain the same.

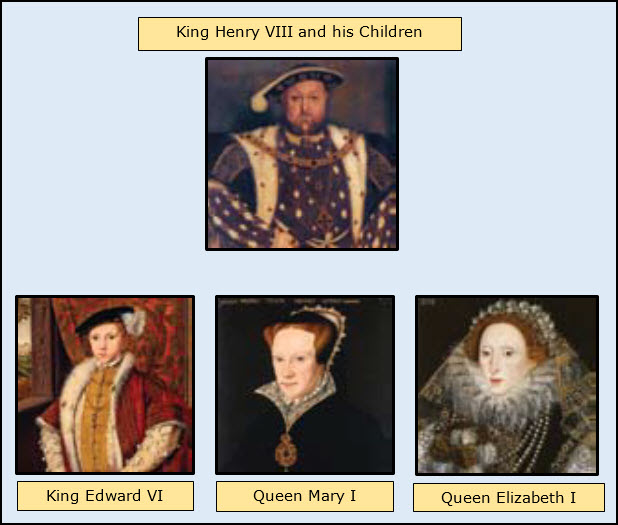

After

Henry VIII died in 1547, all three of his children eventually ruled England,

and each one had a strong religious viewpoint.

First, his son, who was only ten at the time, was crowned Edward VI. His advisors encouraged Parliament to pass

laws that made the Church of England more Protestant. Although the changes were minor, they

resulted in several Catholic uprisings that were harshly put down. Since Edward died as a teenager, his sister

Mary Tudor became queen. Queen Mary I wanted to bring England

back to the Catholic Church. Under her

rule, thousands of Protestants were burned at the stake, including Archbishop

Thomas Cranmer. Mary’s reign was brief,

and her sister Elizabeth inherited

the throne. After ten years of religious

turmoil, the new queen worked to achieve compromises between Catholics and

Protestants with the goal of ending the violence. During her forty-five years as queen or the Elizabethan Era, Elizabeth I kept most

Catholic traditions but affirmed that England was a Protestant nation under the

control of the English crown.

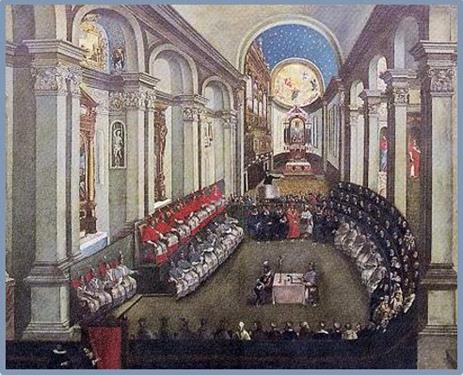

The

Counter Reformation

As

the Protestant Reformation continued to spread, the Roman Catholic Church

recognized that it had to make certain changes if it was going to survive. The driving force behind this movement, known

as the Counter or Catholic Reformation,

was Pope Paul III. From 1530 through 1550, he tried to stop the

Protestant momentum by working to end corruption and by listening to reformers. To establish guidelines for what needed to be

done, the pope called a meeting of European Catholic bishops and

archbishops. Called the Council of Trent, it met on and off for

the next twenty years.

An Artist's Rendition of the Council of Trent

Through

the efforts of this assembly, traditional Catholic values were reaffirmed and

explained. The council recognized the

need for a clergy that was better educated and prepared to answer questions

from Protestants. With this in mind, it passed

measures that provided better training for priests. The assembly also took steps to correct

abuses and to end corruption. At the

same time, Pope Paul III strengthened the power of the Inquisition or Church courts.

To obtain evidence, however, it often relied on secret testimony and

torture. The Inquisition handed down harsh punishments that often resulted in

the execution of the accused. The Church

courts were responsible for compiling and updating the Index of Forbidden Books. These works, including those of Martin Luther

and John Calvin, were considered inappropriate for Catholics to read.

To

counteract the criticism by Protestants concerning monasteries and convents,

Pope Paul III approved a new religious order known as the Society of Jesus or the Jesuits. The group was founded by Ignatius of Loyola, a Spanish knight. After his leg was severely injured in battle,

Ignatius could do little but read as he recuperated. He chose stories about men and women who had

endured mental and physical torture to defend their faith. This inspired Ignatius to organize the

Jesuits, a group of men dedicated to religious training and strict obedience to

the Church. Its members made it their

mission to uphold and spread the Roman Catholic faith throughout the

world. They provided a positive image of

the Roman Catholic Church by serving as teachers, advisers to rulers and

missionaries.

An Artist's Rendition of the Inquisition

In

some respects, the Counter Reformation was a success. The Council of Trent prohibited the sale of

indulgences and other controversial practices.

Church leaders began to focus more on spiritual issues and less on

worldly concerns. Groups like the

Jesuits stressed the importance of understanding one’s faith and the

significance of charity through service.

While these measures improved the Church’s image, other factors, such as

the Inquisition and the Index of Forbidden Books, did not. Nonetheless, the advance of Protestantism

slowed, and some who had left the Roman Catholic Church returned. However, Europe remained divided on issues

concerning the Christian faith as the world entered the Modern Age.

What

Happened Next?

While

Europeans dealt with the events that took place during the Middle Ages and the

Renaissance, other regions of the globe developed their own economies,

governments and cultures. Improvements

in technology, transportation and communication connected Europe with Asia,

Africa and the Middle East, and this resulted in a new era of human history

known as the Frist Global Age. Before

moving on to the next unit, review the names and terms found in Unit 23; then,

answer Questions 21 through 30.