CHALLENGING THE

CHURCH

CHALLENGING THE

CHURCH

Wittenberg,

Germany:† 1536

Unit

Overview†††

The

Roman Catholic Church, which represented all of Europeís Christians throughout

the Middle Ages, was a major social, political and economic force.† Its influence, however, began to decline as

the fifteenth century drew to a close.†

Abuses of power and the spirit of the Renaissance led Martin Luther and

others to question its teachings and its mission.† Thanks to the invention of the printing

press, more Christians were reading and interpreting the Bible on their own.† This led to demands for reform and eventually

to the development of new religious groups.†

Letís see how it all happened.†

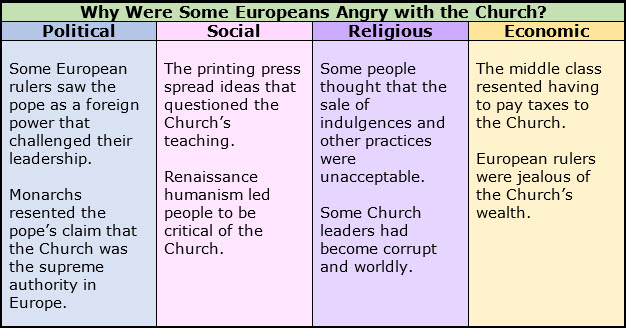

Questions

about the Church†††

The

Renaissance encouraged Europeans to view their world with a critical eye.† With books more readily available thanks to

the development of the printing press, people were exposed to a wider variety

of opinions and philosophies.† Many

traditional values were questioned, including authority of the Roman Catholic

Church.† Many European Christians

concluded that the Church had been abusing its power and had been ignoring its

true mission.† The lavish lifestyle of

the Renaissance popes, who controlled Rome from 1447 to 1534, reinforced this

idea.† These men became increasingly more

involved in Europeís political and economic affairs.† They raised armies to defend the Papal States

and plotted against the rulers of other Italian cities.† As patrons of the arts, the popes used church

funds to hire painters, sculptors and architects.† Although these activities created beautiful

churches and memorable works of art, they required huge amounts of money.†

St. Peter's Basilica:† Construction Started during the Renaissance

Papacy

To

finance their patronage of the arts, the popes approved increases in fees for

services, such as baptisms and weddings.†

The sale of indulgences also

became popular.† An indulgence, granted

by a clergyman, decreased the amount of time a soul had to spend in purgatory, a place of cleansing before

entering heaven.† Traditionally, priests

offered indulgences as rewards for joining crusades or other good deeds.† By the late 1400s, however, people could

obtain them in exchange for a gift of money to the Church.† Many Christians, who were now reading the

Bible on their own due to the printing press, resented this practice.† The middle class, already angry over the

increase in fees, saw indulgences as an easy way for sinners to buy themselves

out of trouble.† For many, it was simply

another sign of corruption within the Church.†

Protests against the practice became common and eventually led to a

full-scale revolt.

Martin

Luther and the Protest of Indulgences†††

In

1517, Martin Luther, a German monk

and theology professor in the German city of Wittenberg, brought the issue of indulgences to the forefront.† A priest named John Tetzel wanted to

collect money for a construction project at St. Peterís Basilica in Rome.† With this in mind, he set up shop on the

outskirts of Wittenberg and sold indulgences.†

He told his customers that their purchases would ensure a quick access

to heaven for them and their relatives.†

Martin Luther was already disillusioned by the corruption of the Church,

and the news of this example was the last straw.

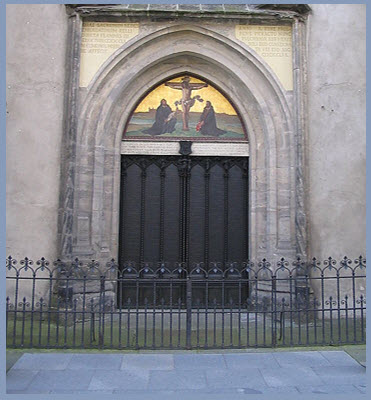

Doors of Castle Church:†

Wittenberg, Germany

Furious,

Luther made a list of ninety-five reasons why indulgences were unacceptable.† For example, he noted that there was no

biblical basis for them and that Christians could only gain admittance to

heaven by faith.† The Ninety-five

Theses, as they came to be called, were written in Latin and intended

for Church leaders rather than the average person.† In Lutherís time, the doors of churches

served as community bulletin boards.†

Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-five

Theses to the main entry of Castle

Church as a form of protest.† This

action did capture the attention of Church officials.† At the same time, the document was quickly

translated into several European languages, printed and distributed across the

continent.† This pushed the Reformation, which began as a movement

to correct abuses within the Roman Catholic Church, into high gear.†

From

Reform to Protest†

†

The

Church demanded that Luther take back or recant his statements.† He refused and urged Christians to reject the

authority of the pope.† It was no

surprise that Pope Leo X excommunicated Martin Luther in

1521.† The dispute between the monk and

the Church soon involved all of Germany.†

In the sixteenth century, German territory was divided into several

states with each one ruled by a prince.†

Together, they made up the Holy

Roman Empire.† Emperor Charles V supported the popeís position

in the controversy.† He ordered Luther to

appear at a diet or meeting of the

German princes in the city of Worms.† Like the pope, Charles V ordered Martin

Luther to admit that he was wrong.†

Again, Luther refused.† The

emperor called him an outlaw and declared it a crime for anyone to offer him

even basic necessities.† Although some

people agreed with the emperor, thousands of Germans considered Luther a

hero.†

An

Artist's Rendition of Martin Luther at the Diet of Worms

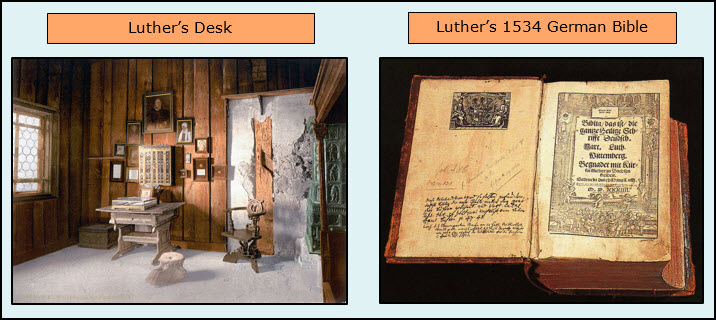

Following

the Diet at Worms, Luther spent the next year in the German province of Saxony.†

Here, Prince Frederick

offered him shelter in his castle. During this time, Luther translated the New

Testament of the Bible into German.†

Because no one had been arrested for assisting him, he returned to

Wittenberg in 1522 and was amazed at the changes that had taken place.† Local priests were conducting services in

German rather than in Latin and were referring to themselves as ministers.† Things were so different that Lutherís

followers thought of themselves as a separate religious group called Lutherans.† By 1530, they were also known as Protestants because they protested the

popeís authority. †

Support

for the Protestant Movement†††

The

Protestant Reformation movement attracted support for several reasons.† Some clergy saw it as an opportunity to clean

up the corruption within the Roman Catholic Church.† In some cases, German princes took advantage

of the situation and seized valuable Church lands for themselves.† Many German middle class citizens simply no

longer wanted to send their hard-earned money to support Church officials in

Italy.† The peasants saw the Reformation

as a way to end the feudal system once and for all.† This viewpoint led to the Peasantsí Revolt in 1524.† When the rebels began to burn churches and

monasteries, however, Martin Luther refused to support their cause.† To restore order, the nobles used their

soldiers to end the rebellion, and this resulted in the deaths of thousands of

peasants.

War

also broke out between the Roman Catholic princes and the Protestant

princes.† Charles V tried to force the

Lutheran rulers to return to the Roman Catholic Church, but he had little

success.† In 1555, the German princes

signed the Peace of Augsburg, an

agreement which permitted each prince to choose the religious faith followed in

his territory.† For the most part, the

northern states adopted Lutheranism while the southern states remained Roman

Catholic.† It was certain, however, that

the Roman Catholic Church would never again represent all of Europeís Christian

population.††

What

Happened Next?†††

Although Martin Luther continued to write sermons and pamphlets until his death in 1546, the Protestant Reformation became less dependent on his leadership.† Other reformers demanded change and challenged the supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church in several parts of Europe, especially England.† Before reading about these events in the next unit, review the names and terms in Unit 22; then, answer Questions 21 through 30.†