FROM REPUBLIC TO

EMPIRE

FROM REPUBLIC TO

EMPIRE ††

††

Unit

Overview††††

After

establishing control over the Italian peninsula, the Romans began to build an

empire by conquering territory around the Mediterranean Sea.† This brought Rome into conflict with Carthage,

an equally ambitious city in northern Africa.†

The two cities fought a series of wars to determine which one would

dominate the region.† Although Rome emerged

victorious, the Carthaginian Wars would have both positive and negative

long-term effects for Roman state.† Letís

see how it all happened.†

The

Wars with Carthage†††

Carthage, once a colony of the Phoenicians,

was located on the coast of northern Africa and, like Rome, had plans to

dominate the area around the Mediterranean Sea.†

This made conflict between the two cities inevitable and resulted in a

series of wars known as the Carthaginian

or Punic Wars.† When war broke out

between the two cities for the first time in 264 B.C., both sides had certain

advantages.† Carthage, the larger of the

two, had directed its energy to making money through trade.† With their wealth, the Carthaginians had

built a navy with over 500 ships and hired neighboring peoples to serve as

soldiers.† The Romans, on the other hand,

had no actual navy.† Since they had spent

their energy on making war rather than making money, the Romans did have an

experienced, well-trained army with 500,000 troops at their disposal.† Their solders were more reliable and more

loyal than those employed by the Carthage.†

When a Carthaginian warship ran aground in Italy, the Romans received a

remarkable piece of good luck.† They made

140 copies of the ship and added a few touches of their own.† The Romans were then in a better position to

compete with the Carthaginians on the sea.†

The First Punic War was over control of the

island of Sicily and dragged on for

twenty-three years.† Rome finally

defeated Carthage, and the victory awarded Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica to

Rome.† For the next forty years, Rome and

Carthage maintained an uneasy peace.† In

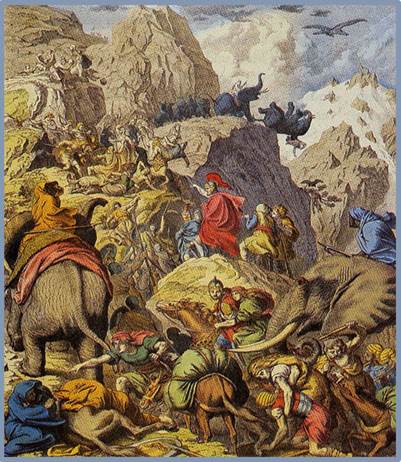

218 B.C., the Carthaginian general Hannibal organized his forces at a base in

Spain and prepared to attack Rome in the Second

Punic War.† He led his army,

including several dozen war elephants, across France and over the Alps to raid

Rome from the north.† Even though this

plan cost the lives of half of his soldiers, Hannibal took the Romans by

surprise and won battle after battle for fifteen years.†

In

spite of his success, Hannibal was unable to capture the city of Rome

itself.† Desperate to get enemy out of

Italy, the Romans sent an army to Carthage.†

This was a risky move, and not all Romans thought it was good idea.† When the Romans began to arrive outside of

their city, the Carthaginians demanded that Hannibal bring his army home to

defend them.† Hannibal had little choice

but to comply.† The Romans defeated the

Carthaginians in a battle near Carthage, and the Second Punic War was another

win for Rome.†

Artist's

Rendition of Hannibal Crossing the Alps

The

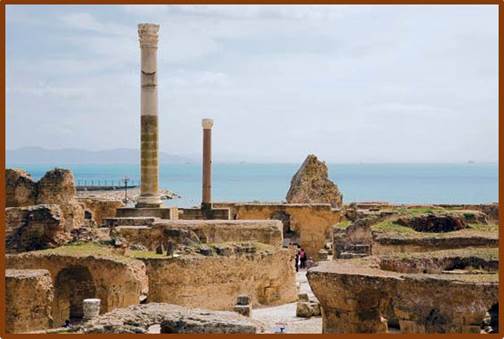

damage done in Italy by Hannibalís army left the Romans with a desire for

revenge that was not satisfied by winning the Second Punic War.† Many Romans argued in favor of the complete

destruction of Carthage.† This resulted

in the Third Punic War and the

obliteration of Carthage.† Those who

survived the attack were sold into slavery, and salt was poured over the soil

so nothing could grow there again.† There

was no question that Rome was the undisputable master of the western

Mediterranean.†

At

the same time, Rome extended its power across the eastern Mediterranean and

battled the rulers who had divided the empire of Alexander the Great.† Greece, Macedonia and sections of Asia Minor

surrendered to the Romans and became provinces,

a term used for lands under Roman rule.†

Other areas, such as Egypt, formally became Roman allies.† It appeared that Rome was dedicated to

following a policy of imperialism or

the establishment of control over other lands.

Ruins

of Carthage

The

End of the Republic†††

Rome

not only conquered vast amounts of territory but also gained control of several

major trade routes.† As money poured into

the city from taxes and increased business, a new class of wealthy Romans

formed.† The built impressive mansions

and filled them with luxuries from distant lands.† Some rich families used their money to buy

country estates and turned them into large farms called latifundia.† As Romans added

new territory to their holdings, they made even greater profits by forcing

captured people to work as slaves.† The

price of grain in the Roman markets quickly fell, and small farmers in Italy

were forced to sell their property to pay their debts.† Without land to farm, the unemployed moved to

Rome and other cities with the hope of finding work.† As the gap between the rich and the poor grew

wider, angry mobs roamed the streets, and riots became common.

Although

there were attempts at reform, the republic was unable to solve its social and

economic problems.† A series of civil

wars rocked the Italian peninsula, and unrest spread throughout Romeís

provinces.† Popular political leaders

challenged the traditional role of the Roman senate.† The Roman army, no longer made up of

citizen-soldiers, consisted of men who signed up to serve for sixteen years. †They became professional soldiers and were

willing to fight for any leader who rewarded them.† This made it possible for rival politicians

to form their own armies and to take control by force.

The

Career of Julius Caesar††

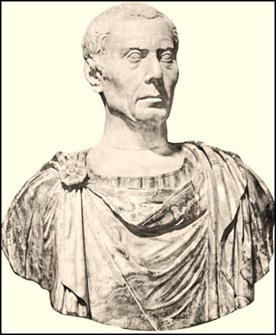

Julius Caesar, perhaps the most famous

Roman of them all, was a master at using a loyal army to further his

ambitions.† In 59 B.C., he set out to

conquer Gaul, which consisted mostly

of modern-day France.† After nine years

and a successful military campaign, a triumphant Caesar prepared to return to

Rome with his army. †Pompey, his chief rival, convinced the

senate to command Caesar to disband his troops and to come to Rome without

them.† Caesar defied the order and

marched toward Rome with his army.† In

the civil war that followed, Caesar defeated Pompey and forced the senate to

appoint him dictator.

Julius Caesar

Although

he kept several features of the republic, including the senate, there was no

doubt that Julius Caesar was the absolute ruler of Rome.† In an effort to fix Romeís issues, he gave

public land to the poor and established a government-sponsored works program to

create jobs.† Along with granting

citizenship to more people, Caesar introduced a new, 365-day calendar which,

with minor changes, we still use today.†

In spite of these efforts, Caesarís enemies plotted against him, and he

was assassinated in 44 B.C.† To learn

more about the life and career of Julius Caesar, view the video listed below.

The

death of Julius Caesar plunged Rome into a new round of civil wars.† Octavian,

Caesarís great nephew, and Mark Antony,

one of Caesarís trusted generals, were determined to track down the

murders.† After they accomplished this,

the two men engaged in a bitter struggle for power.† In a sea battle, Octavian defeated Mark

Antony and his ally Cleopatra, queen

of Egypt.† The senate gave Octavian the

title of Augustus (Excellent One)

and declared him the princeps or

first citizen.† This ended the Roman

republic and made Augustus the first emperor of Rome.

Augustus

Takes Charge†††

Augustus

worked to return stability to Rome.† Like

Julius Caesar, he left the senate in place but added a civil service.† This action

created an efficient system of workers to make sure everything operated

smoothly and to enforce the laws.† They

collected taxes, represented Rome in the provinces and supervised construction

projects.† Augustus ordered a census or a population count

throughout the empire.† New coins were

issued to make it easier to conduct business, and a postal service delivered

mail to Britain and other distant provinces.†

To create jobs, Augustus ordered a number of construction projects, and

an efficient system of roads soon connected outlying territories to Rome.

Pax

Romana††

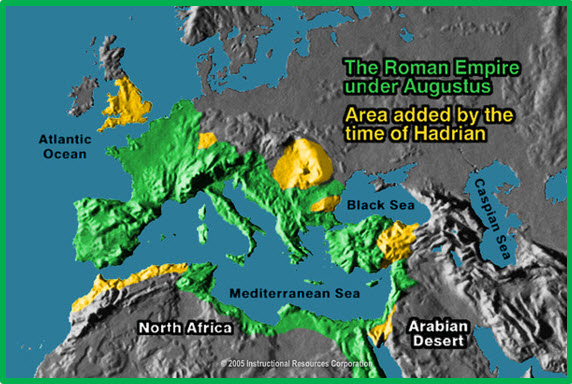

The

reign of Augustus began a 200-year period known as the Pax Romana, a Latin phrase that means the Roman peace.† During this era, Rome and its territories,

for the most part, experienced peace, prosperity and order.† The Roman army patrolled the network of roads

throughout the empire, and Roman ships protected the seas from pirates.† As a result, travel was relatively safe, and

advancements in transportation made it faster.†

Trade flourished, and new products came from everywhere.† Spices from India, silk from China and wild

animals from Africa could all be found in Rome.†

At the same time, ideas and knowledge were exchanged across the

empire.††

Not

all of the emperors that followed Augustus were good rulers.† Some, like Nero and Caligula, were incompetent

and cruel.† There were others, however,

like Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius, who were committed to good leadership.† Click on the graphic below to discover which

Roman emperor was the most like you.† In

an attempt to gain public support and to quiet any unrest, most emperors

offered free grain to the poor and used tax dollars to provide spectacular

public entertainment.† Romans of all

social classes loved the chariot races held in the Circus Maximus and enjoyed

watching the gladiators in the Coliseum.†

Similar activities took place in Roman-style arenas built throughout the

empire.† During the Pax Romana, Romeís

political and social problems still existed but remained just below the

surface.†

What

Happened Next?††††

The

impact of ancient Rome extended far beyond famous leaders and military

accomplishments.† Its achievements in

engineering, literature and law continue to impact our daily lives.† The rise of Christianity within the empire

and the Roman reaction to this faith has shaped our thoughts and

traditions.† Before exploring these

topics in the next unit, review the names and terms found in Unit 7; then,

complete Questions 21 through 30.