Rocks and Their Formation

Course

Overview

Earth and space sciences are investigated in more detail in

this course. Earth's characteristics, resources and location in the solar

system are identified and their implications explored. Students also learn

about the interrelationship of organisms and ecosystems and simple food chains

and food webs. Energy and energy transfer through an electrical current are

addressed. Students will describe and illustrate the design process and

describe the positive and negative impacts of human activity and technology on

the environment. Students observe, measure and collect data when conducting a

scientific investigation; students use this information to formulate inferences

and conclusions; and students develop skills to communicate the results.

Labs - In this course, there may be some lab activities that require normal household items for completion. If you do not have the items required for a particular lab activity, please contact your online teacher for accomodation.

Unit Overview

In this

Unit we will talk about the crust of the earth, rocks, volcanoes and

earthquakes and how each influences the characteristics of the earth’s surface.

You will read a short story about a young boy named Paul. Read to find out what

Paul discovered in his own backyard.

You can see how Paul’s mother pictured the history of the

area. If Paul had not left out so much, his mother might not have been so

confused.

What Is Rock?

Paul never did get around to saying what a rock is. Everyone

knows that there is a hard material called “rock” which is found in some road

cuts, hillsides, and riverbanks. You know that it is covered up in most places

by dirt and plants. You know that it is a natural material. Rock is the

solid part of the earth’s crust, is made of minerals, not part of any

living organism, and not made by man. Smaller pieces which have broken off from

the main mass of rock are usually called “rocks.”

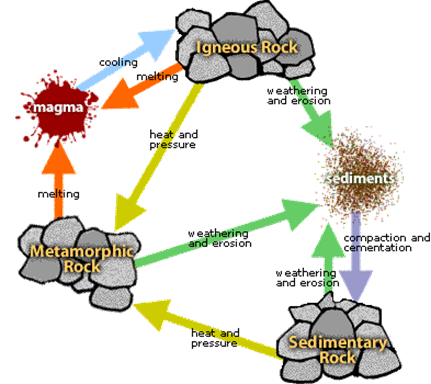

There are three kinds of rocks and, Geologists, who

are scientists who study what makes up the earth and how the earth changes,

understand and explain these differences.

Molecules in rocks may line up in regular patterns called Crystals.

Crystals sometimes form when some liquids turn to solids. For example, ice

crystals and snowflakes form when liquid water freezes. So mineral crystals may

tell us that some forces were once melted and part of a “mineral soup.” The

real buried mineral soup is called magma. To turn into rock, magma has

to cool. Rocks formed from magma are called igneous (IG-nee-us) rocks,

meaning “from fire.”

Here is an experiment to do. It involves growing crystals

around different objects. Have an adult help you with the heating of the water.

Watching Crystals Grow

Objectives

· Observe

and record factors that influence crystal growth.

·

Identify the structure of crystals.

Select and safely use the following materials:

![]() Ten or more shallow bowls (such as

petri dishes)

Ten or more shallow bowls (such as

petri dishes)

Five small, clean rocks

Five small, clean rocks

![]() Four small miscellaneous objects

(such as nails, aluminum foil, shells, or marbles.)

Four small miscellaneous objects

(such as nails, aluminum foil, shells, or marbles.)

Pan for heating, heat source

Spoon and measuring cup ![]()

Four cups of Epsom salts (not table

salt, but crystals of hydrated magnesium sulfate available at most pharmacies)

Two cups of water ![]()

Magnifying glass ![]()

Flashlight ![]()

Observation sheets

Observation sheets

Proceed with care.

1. Separate the bowls into five

pairs. Place small rocks in one of each pair. Choose several small,

miscellaneous objects to put into four of the other bowls. Leave one bowl

empty. Number each bowl.

2. Heat two cups of water in the pan, slowly adding the four cups of Epsom

salts. Continually stir the mixture so that the salts dissolve, but don't allow

it to boil!

3. Divide the mixture among the ten bowls. Don't worry about dividing it

exactly, but make sure that the mixture completely covers the objects in the

bowls.

4. Put two drops of food coloring in the center of several of the bowls.

5. Put five of the bowls in a cool part of the room and five in a warm part of

the room, where they will not be touched or disturbed.

Use Evidence and Observation to Explain and Communicate the

Results of the Investigation. You will record the results by answering the questions in

the questions segment.

·

Questions 1-7 below refer to Bowl 1

·

Questions 8-14 refer to Bowl 2

·

Questions 15-21 refer to Bowl 3

·

Questions 22-28 refer to Bowl 4

·

Questions 29-35 refer to Bowl 5

·

Questions 36-42 refer to Bowl 6

·

Questions 43-49 refer to Bowl 7

·

Questions 50-56 refer to Bowl 8

·

Questions 57-63 refer to Bowl 9

· Questions 64-70 refer to Bowl 10

You should observe the bowls at the start (immediately after the water is

poured into the bowl) and write down what you see. At this point the liquid

should be clear and not have any solid particles in it.

Now observe the bowls again after a few hours if possible and write down any

changes you see. At this stage the crystals should begin forming, but there

will also be a lot of liquid left.

Continue the observation for several days until crystal

formation has stopped. As the crystals form, remove a few for observation under

a magnifying glass or microscope.

On paper draw a series of pictures of the crystals as they

grow, focusing on the shape and growth patterns. Think about the following

points. These will help as you record your observations in questions 1-70.

· Do the crystals have any similarities

in terms of shape and symmetry when observed under the microscope or with a

magnifying glass?

· How many sides (faces) does each of

the crystals have?

· Does shining a flashlight on the

surface of the crystals affect their appearance?

· When did the crystals stop growing?

Did some stop growing before others?

· Did temperature affect the rate of

crystal growth or the size of the crystals? Were warm or cold temperatures more

favorable?

· Did crystals grow in all the bowls?

If not, what may be some of the reasons why the crystals did not grow?

· Did crystals appear to grow more

easily on rocks or metal? On smooth or rough objects?

· Compare and contrast: Look through a

magnifying glass at commonly occurring crystals such as table salt and refined

sugar.

· How are these crystals similar to and

different from those grown in dishes?

You should notice that crystals do not grow easily on smooth

surfaces like marbles or metal. You also should observe that the dishes that

cooled slower should have larger crystals but took longer to form. Everything

does not always go right when you do an experiment, so look for factors that

may have made a difference in the results.

Table sugar crystals, magnified 100

times

If you have any questions contact your Virtual Learning

teacher.

Now, some major points

to remember.

· Magma is a mixture of melted

minerals.

· Rocks that form from magma are called

igneous rocks.

· The heat to melt minerals comes from

the original heat inside the earth and from radioactive decay.

· Fast cooling will probably produce no

crystals at all, medium-fast cooling usually produces medium sized crystals,

and slow cooling produces large crystals.

Rock at the surface of the earth naturally breaks up. The

weather, running water, chemicals, and man all contribute to the process of

rock deposits breaking into “rocks”. It is chipped, splashed on, eaten by

acids, and carried away a piece at a time by streams. The pieces, called sediment

(SED-ih-ment), eventually collect in deposits or piles. Follow a stream some

time and see if you can find one of the sediment deposits. Look at a handful of

sand. Where did it come from? Could it have come from a piece of granite? Could

other types of rock besides granite be a part of that sand? Yes, of course

other types of rock can be broken down. When this sediment is deposited, at the

end of a river or at the bottom of a large body of water, all those pieces

become cemented together after eons of time to form another rock. Rocks that

have been made by cementing sediment together are called sedimentary

(sed-ih-MEN-tree) rocks.

You can make your own sedimentary rock by mixing 1/2 cup of

glue and 1/2 cup of water together. Let it stand for a few minutes. Take a

paper cup and punch about ten small holes in it. Then, put a handful of pebbles

or crushed stone from a driveway into the paper cup with the holes. Pour the

glue mixture through the cup. Have another cup underneath to catch what runs

out the holes. Wait a few minutes. Then pour what you caught back over the

pebbles and again catch what runs out. Keep doing this a few more times,

remembering to wait a few minutes between each pouring. After you are done put

the cup in a warm place to dry overnight. The next day tear the paper cup off.

What you are looking at is a sample of Sandstone.

There are many other kinds of sedimentary rocks. Some

sedimentary rocks do not need cement like the glue to keep them together.

Sedimentary rocks contain records of the past.

Major points:

· Pieces of rocks can become cemented

together to form new rocks.

· The dissolved shells of sea animals

can act as cement.

· The rocks formed by the cementing of

small pieces of sediment is called sedimentary rock.

· Sedimentary rocks may contain records

of the past events and past life.

· Minerals or other compounds that have

been left behind as water evaporated or that have dropped out of a water

solution because of temperature changes also form sedimentary rocks.

What happens to rock pieces after they have been cemented

together? Rain, wind, chemicals, and ice still erode them. Streams still carry

off the chipped-away pieces if the rock gets to the Earth’s surface. But, what

happens to rock that doesn’t get to the surface? Suppose more and more sediment

keeps piling on top of it. Will it remain sedimentary rock forever? Maybe the

sedimentary rock will be buried so deeply that the heat of the earth begins to

raise the temperature of the rock. The sedimentary rock could get hot enough to

turn into magma. The new magma might even reach the surface to start the entire

process all over again.

Geologists have found that this does happen to some

sedimentary rock. But, they have also found that sometimes sedimentary rock

melts and cools again without turning into magma. Sometimes, tremendous

pressure squeezes the rock until the minerals actually flow, without melting.

Rock that has been changed by heat or pressure or both is

called metamorphic (met-uh-MOR-fik) rock. This changing process

sometimes makes the metamorphic rock harder than the original rock.

Rock that has been changed by heat or pressure or both is

called metamorphic (met-uh-MOR-fik) rock. This changing process

sometimes makes the metamorphic rock harder than the original rock.

Not only can sedimentary rocks be changed, but also, igneous

rocks can be changed.

Major points:

· Rocks can be buried deeply enough to

melt again. A new igneous rock may then be formed.

· Rocks can be changed by heat and

pressure. These rocks are called metamorphic rocks.

· While igneous rocks are in the liquid

(magma) form because of heat and pressure, some of their crystals may change

structure and flow.

· When sedimentary rock changes form,

the new rock is sometimes harder and sometimes contains more kinds of crystals.

For additional information on rocks, click on this link https://www.rocksforkids.com/

Make sure that you looked at all the types of:

I. Sedimentary Rocks: Sandstone,

Limestone, Shale, Conglomerate and Gypsum.

II. Metamorphic Rocks: Schist and

Gneiss

III. Igneous Rocks: Granite, Scoria,

Pumice and Obsidian