WHY WE TRADE

Chinese Factory Workers Preparing Goods for Export

Unit

Overview

Very

few days pass in the United States without media headlines concerning

international trade. Should the United

States impose sanctions that limit trade with certain countries? Do the trade policies of other nations give

them an unfair advantage? How should

Americans respond to concerns about the trade deficit? All of these issues sometimes make people

wonder if trade is really worth the hassle.

Economists, however, maintain that international trade improves the

global standard of living and encourages healthy economic competition. They use the basic principles of economics to

explain why this is true. Let's see how

it all works.

Why Do

We Trade?

Why

do we trade? For the most part, nations

trade for the same reasons people do.

They believe that the goods and services received are more valuable than

those which they are giving up. If you

ask an economist this question, he or she would likely answer that trade

happens because resources are scarce and unequally distributed around the

globe. Within their borders, countries vary

dramatically in the amount of land available for farming, mineral deposits, oil

reserves, timber and other things too numerous to list. Climate and geographic features, such as

mountains, waterways and desserts, also limit a nation's ability to produce all

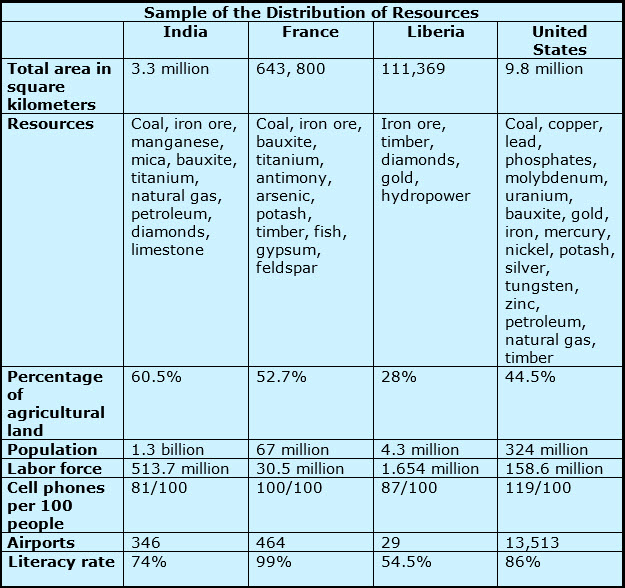

the goods and services that citizens want and need. The table below compares four countries in

eight categories. Each nation possesses

different natural, human and physical resources. Trade is one way for a nation

to make up for what it lacks.

At

the same time, there are major differences in the available physical capital, or human-made

materials, needed to create certain goods.

Infrastructure, including roads and bridges, airports, factories, power

plants, tools and machinery, fall into this category and are not readily

accessible in some regions of the world.

Industry also requires human capital, or skilled workers. To measure a country's human capital,

economists often refer to the literacy

rate. This is the percentage of

people over the age of fifteen who can read and write. A high literacy rate likely represents an

educated and capable work force. History

and culture, too, play a role in a country's allocation of resources. For example, long periods of civil warfare or

frequent invasions tend to reduce a nation's capacity to produce goods and

services.

We

also trade simply because it gives us more of what we want. When

today's shopper visits a mall, he or she is likely to come home with clothes

from China, shoes from Indonesia and a bicycle helmet made in France. This extensive variety of products is the

result of international trade. It gives

consumers more choices, lowers costs and improves quality by encouraging competition. At the same time, statistics seem to indicate

that countries engaged in international trade develop a higher standard of

living. Trade also creates a global economic interdependence that builds

relationships and promotes peace.

However, like all decisions, the choices surrounding international trade

come with opportunity costs.

![]() Go to Questions 1 through 6.

Go to Questions 1 through 6.

Absolute

and Comparative Advantage

How

do nations decide what to produce, how to produce and for whom to produce goods

and services when it comes to trade? Because

countries differ in resources, capital, climate and geography, they sometimes

concentrate on certain items rather than producing everything themselves. This is referred to as specialization. For example, Guatemala has very limited mineral

resources, but it does have the right soil and climate to produce large

quantities of bananas. By exporting

bananas, it earns the money to purchase products that it cannot manufacture

efficiently. Does this example mean that

a country with ample resources has no reason to trade? If a nation has access to the latest

technology and has educated a well-trained workforce, can it ignore global

trade and become self-sufficient? In

reality, countries with more-than-adequate resources as well as limited ones

can benefit from trade. Two economic

concepts, absolute advantage and comparative advantage, explain why this is

possible.

When

one country produces more of a particular product than other nations who

manufacture less with the same amount of resources, it is said to have an absolute advantage over its competitors.

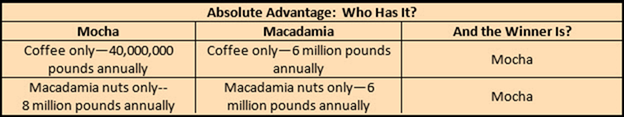

Let's see how it works with the imaginary countries of Mocha and Macadamia. Both countries are almost equal in size,

population and available capital. Each

one only grows two crops—coffee beans and macadamia nuts. If both countries dedicate all their

resources to growing coffee beans, Mocha can produce 40,000,000 pounds of coffee

annually, while Macadamia can only produce 6,000,000 pounds of the same good in

the same time period. Clearly, Mocha has

the absolute advantage. What happens if

both countries shift to growing only macadamia nuts? Mocha produces 8,000,000 pounds of nuts, but

Macadamia produces 6,000,000 pounds.

Once again, Mocha has the absolute advantage.

At first,

economists believed that absolute advantage was the basis for trade because it

permitted a country to manufacture enough of a particular good to satisfy its

population and to sell the remainder in the world market. However, it soon became obvious that trade

benefitted countries with abundant resources as well as those with few

resources. In the early nineteenth

century, David Ricardo, a British

economist, argued that the key to trade is not which country produces the most

of one product with the fewest resources but the country that produces the most

at the lowest opportunity cost. This concept is referred to as comparative advantage. Remember—opportunity cost is what you give up

when you choose to do one thing rather than another.

Let's

take a second look at Mocha and Macadamia using comparative advantage. If Mocha shifts its production to macadamia

nuts only, it gives up 40,000,000 pounds of coffee. This is an opportunity cost of five pounds of

coffee for every one pound of macadamia nuts produced. For Macadamia, the opportunity cost that

results from growing just macadamia nuts is much lower. Because it is giving up 6,000,000 pounds of

coffee beans to produce 6,000,000 pounds of macadamia nuts, the opportunity

cost for 1 pound of nuts is 1 pound of coffee.

Since the same pound of macadamia nuts costs Mocha five pounds of

coffee, Macadamia has the comparative advantage for this product.

Who

has the comparative advantage when both countries shift to producing just

coffee? For every one pound of coffee

that it produces, Mocha gives up 1/5 pound of macadamia nuts. If Macadamia produces only coffee, its

opportunity cost is one pound of macadamia nuts. When it comes to coffee, Mocha has the lower

opportunity cost and, therefore, the comparative advantage. The citizens of

Mocha actually make more money by producing coffee and, in turn, by trading for

macadamia nuts. This is a good

illustration of the law of comparative advantage, which says that a nation is

better off when it produces goods and services that result in a comparative

advantage. It can then use the money to

buy other goods that it cannot produce as efficiently.

Here

is an example of how two real countries use comparative advantage so that each

one benefits. The United States has the

resources, physical capital and skilled labor force to manufacture farm

equipment at a comparative advantage.

Columbia, however, does not. It

does have the climate, capital and skilled labor required to produce coffee

beans. Because Columbia has the

comparative advantage in the production of coffee beans, it concentrates of

that particular good and exports coffee to the United States. Through this transaction, Columbia earns the

money to purchase farm equipment from the United States. The United States benefits by selling the

farm machinery and by having access to a supply of coffee. This makes the two countries trading partners. Trading partners often negotiate agreements

so that each country gets the most for its money.

![]() Go to Questions 7

through 14.

Go to Questions 7

through 14.

Trade

Surpluses and Deficits

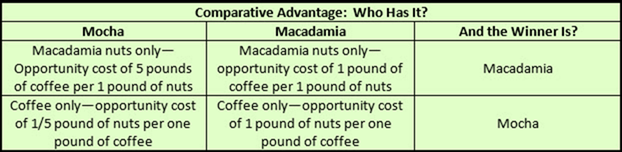

In

terms of world trade, the United States is a major exporter and a major importer. An export

is a good that is sent to another country for sale. The United States has a wide range of

exports, including medical equipment, vehicles, agricultural products,

plastics, spacecraft and computer software.

Although goods make up most of the items sold in the global market,

services, such as educational programs, data processing, financial services and

medical care, have grown in recent decades.

Imports, on the other hand,

are goods brought in by other countries for sale. America's top imports include oil, furniture,

machinery, pharmaceuticals, vehicles and precious metals. Note that there are some things that the U.S.

imports and exports. The countries with

whom the United States exchanges the most goods and services are listed in the

charts below.

Nations

traditionally have preferred to maintain a balance of trade so that the value

of their imports roughly equals the value of their exports. This keeps their currency stable in the

international market. When a country's

exports are greater than its imports, it experiences a trade surplus. Currently,

China, Russia and Japan run large surpluses of trade. When a country imports more than it exports,

a trade deficit occurs. Spain, the United Kingdom, Australia, Mexico

and Brazil often have trade deficits, but the United States over several

decades has accumulated the world's largest trading deficit.

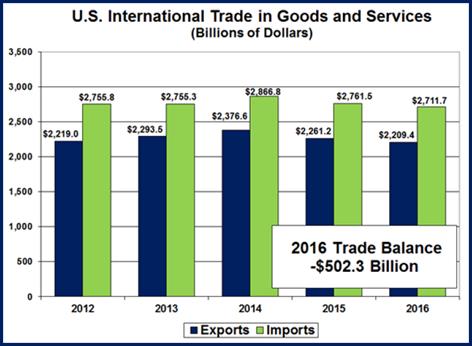

Information

Courtesy of the Bureau of Economic Analysis:

U.S. Department of Commerce

The

massive U.S. trade deficit, which climbed to over $500 billion in 2016, is a

subject of continuous debate. Some

economists predict that it will result in the decline of the gross domestic

product and in the loss of American manufacturing jobs. These same experts expect the trade deficit

to weaken the American dollar, to increase inflation and to promote the sale of

U.S. assets to foreign interests. It

also makes it easier for countries to become currency manipulators.

Through the process of selling their own currency and buying foreign

cash, such as the U.S. dollar, nations can devalue their own money and gain an

advantage in the global marketplace. The

diagram below explains how it works.

At the same time, other economists claim that

trade deficits are positive. By shifting

the production of certain goods to countries outside the United States,

American businesses use their resources more efficiently. The dollars that U.S. citizens spend on

foreign products eventually have to go somewhere. Often, this cash makes its way back to the

United States through investments in American companies. This money funds

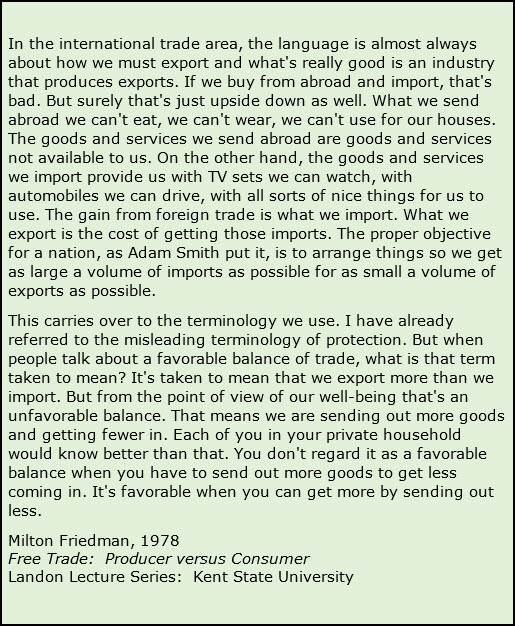

research, new technology and upgraded equipment. Milton

Friedman is one economist who believed that Americans needed to rethink

their view of the trade deficit. Before

his death in 2006, Friedman served as economic advisor to President Ronald

Reagan and won a Nobel Prize in economic sciences. In a passage from one of his speeches quoted in

the graphic below, he suggests that perhaps we are simply looking at it

wrong. Is a deficit bad and a surplus

good? According to Friedman, it may be

just the opposite.

![]() Go to Questions 15

through 22.

Go to Questions 15

through 22.

What's

next?

Although

international trade has its benefits, workers and businesses sometimes experience

its painful side effects as cheaper, foreign goods enter the marketplace. This can result in lost jobs and closed

plants. In an attempt to solve these

problems, governments add regulations, or trade barriers, to limit the influx

of certain goods. Are these measures

effective? Do they create more problems

than they solve? Do they really save

jobs? Before answering these questions

in the next unit, review the names and terms found in Unit 15; then, answer

Questions 23 through 32.

![]() Go to Questions 23

through 32.

Go to Questions 23

through 32.

|

| Unit 15 Main Points Worksheet |

| Unit 15 Calculating Comparative Advantage Worksheet |

| Unit Ah non! As croissants go global, France butter shortages bite Article and Quiz |