DEMAND:† THE CONSUMER RULES†

The Law of Demand Pictured on a Demand Curve

Unit

Overview

If

someone asked you to define the word demand,

you would probably say that it is the desire to have a particular item.† To an economist, however, demand is something

more.† Yes, it is the desire for a

particular product, but it is also the ability and willingness to pay for that

product.† How does this affect the

decisions of what, how and for whom to produce?†

What is the relationship between the price an individual is willing to

pay and the quantity in demand?† What

changes affect the demand curve, and how do they impact consumers?† You will find the answers to these questions

in this unit so letís get started.

How an

Economist Defines Demand

The

study of economics is divided into two major categoriesómicroeconomics and macroeconomics.† The two terms are based on the Greek prefixes

micro, meaning small, and macro, meaning large.†

Macroeconomics examines the big picture by focusing on the behavior and

decision-making of entire economies.† On

the other hand, microeconomics analyzes the behavior and decision-making of

smaller units, such as individuals, families, households and businesses.†

One

important topic covered under microeconomics is the concept of demand.† Generally, people think of demand as the

desire to own a particular item.† For an

economist, however, desire is just one of the factors that creates a demand for something.† Consumers must not only want a product but

must also have the ability and willingness to pay for that product.† In the market system, buyers demand goods,

and sellers supply them.† This

interaction between the two groups leads to agreement on the price and the

quantity that is produced.

Go to Questions 1

and 2.

Go to Questions 1

and 2.

The

Law of Demand

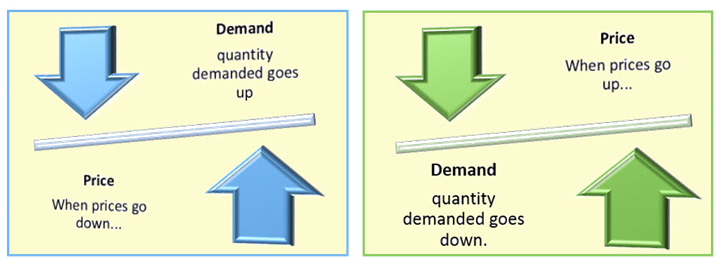

The law of demand simply puts into words

something that every consumer knows to be true.†

It states that consumers buy more of a good when its price decreases and

less of a good when its price increases.†

In other words, when the price of a certain product is high, consumers

will buy less; when the price is low, consumers will buy more.† All of us recognize this on a daily basis

when we make purchasing decisions.† For

example, would you buy a doughnut for breakfast if it cost $1?† In fact, at that price, you might even buy

two or three.† Would you buy that same

doughnut if it cost $2?† It is likely

that fewer people would purchase a doughnut at this price.† Even a true doughnut lover would probably

purchase one or two rather than three or four under this condition.† As the price of a doughnut goes higher and

higher, fewer and fewer people will agree to buy it.

Go to Questions 3

and 4.

Go to Questions 3

and 4.

Human

Behavior and Demand

The

law of demand is the result of three patterns of human behavior.† The substitution

effect, the income effect, and

the principle of diminishing marginal

utility describe different reactions that encourage consumers to change

their spending habits.† They also explain

why price increases or decreases influence the number of goods that are

purchased.† When the price of a doughnut

goes up, doughnuts become more expensive than other options, such as breakfast

sandwiches or bagels.† This causes a drop

in the number of doughnuts demanded by buyers.†

A consumer could eat breakfast sandwiches three days a week and could

decide to purchase doughnuts only two days per week.† †This change

in spending habits is due to the substitution effect.† Consumers react to an increase in prices by

purchasing less of one good and more of another.† The substitution effect also occurs as a

result of a drop in prices.† When the

price of doughnuts goes down, consumers will buy more, and the demand for

doughnuts will increase. They will be less likely to purchase other breakfast

items as substitutes.

Televisions:† Name Brands or Lesser-Known Brands?

A

change in prices impacts our feelings and emotions.† If costs increase, we feel poorer.† When our limited budgets no longer cover as

many concert tickets, clothes or doughnuts as they once did, we feel as if we

have less money and cut back on some items.†

The income effect occurs when we buy fewer doughnuts without increasing

our purchase of other foods.† Of course,

the income effect operates in reverse when prices decrease.† We feel wealthier when prices are lower.† This leads to greater spending and increased

demand.†† It is also the basis for the

law of demandówhen a goodís price is lower, people buy more of it; when a

goodís price is higher, people buy less of it.

As

you know, economists apply the word utility to describe the usefulness

or satisfaction that a person receives from a particular good or service.† It is, after all, the reason that we purchase

something in the first place.† However,

do we get the same amount of satisfaction when we buy more than one of the same

item?† The answer to this question is

based on the economic principle of diminishing marginal utility.† Consumers derive the most satisfaction from

their first purchase of a particular product and less if they buy the same

product a second time.† Utility continues

to decrease, or diminish, with each additional purchase of the same good.† For example, when you buy a newspaper, why do

you not buy more than one copy of the same publication?† Buyers gain little or no satisfaction from

reading the same stories again.†

Therefore, additional purchases of the same newspaper are subject to

diminishing marginal utility.

Go to Questions 5

through 7.

Go to Questions 5

through 7.

Illustrating

the Law of Demand

Mark

is chairperson of the student councilís fund-raising committee at his

school.† The committee has decided to

raise money by selling doughnuts before classes every morning for a few

weeks.† The members have decided on the

type of doughnut to sell but are debating how much to charge per doughnut.† They conduct a poll to see what prices

students would be willing to pay for this item.†

To analyze this information, however, Mark and his committee need to

think like economists.

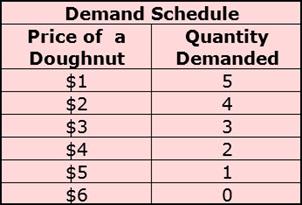

A demand schedule is a tool used by

economists to organize data.† It lists in

a table the quantity of a good that people will buy at each price in the market.† The table below shows the numbers of

doughnuts that students are willing and able to purchase at specific prices.

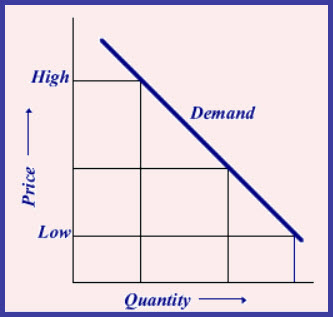

The

committee could also study the figures on this demand schedule by plotting them

on a graph known as a demand curve.† It pictures the quantity demanded at each and

every price that might be present in the market.† When an economist transfers the numbers from

a demand schedule to a graph, he or she always marks the vertical axis with the lowest possible price at the bottom and the

highest one at the top.† The horizontal axis shows the lowest

possible quantity demanded on the left and the highest on the right.† Each pair of price and quantity-demanded

numbers from the schedule are plotted on the graph.† The demand curve emerges when the economist

connects the points. †

Notice

that the demand curve slopes downward to

the right.† As the price decreases,

the quantity demanded increases.† This

means that a demand curve is just another way of stating the law of demand, which

emphasizes that higher prices will always result in less demand.† All demand schedules and curves support the

law of demand.† However, demand schedules

and demand curves have limitations.† They

both assume that other factors, which could affect demand, remain the

same.† In the case of doughnuts, the

quality, size and ingredients could affect the studentsí demand for the

product.† In other words, demand

schedules and curves are only accurate as long as there are no changes other

than price.† Economists refer to this

assumption as ceteris paribus, a Latin phrase meaning all other things remaining the same or constant.† When price is the only thing that changes, we

move along the same demand curve to a different quantity demanded.† The curve itself, however, does not move.

Go to Questions 8

through 13.

Go to Questions 8

through 13.

Why

Demand Shifts

As

you have already discovered, economists often define words or phrases

differently than the average person would expect.† This is especially true of the terms demand

and quantity demanded.†

Economists define demand as a consumerís desire, willingness and ability

to purchase something.† Demand is created

when the buyer wants the product and is able to afford it.† In contrast, quantity demanded represents the

exact amount, or quantity, of a good or service that the consumer is willing to

buy at a specific price.†

Changes

in quantity demanded are due to price, and all other things remain constant (ceteris paribus).† Increases or decreases in demand, however,

result from changes in a number of other factors, such as consumer income,

consumer taste, population, expectations and related goods or services. Economists

call these influences determinants.† When consumers are willing to buy different amounts of the product at the same

prices, the demand curve itself shifts to the right if demand increases or

to the left if demand decreases.†††

ō Consumer Income:† A

change in consumer income is one determinant that can affect demand.† If incomes increase, buyers purchase more

products and choose higher-priced goods and services.† Items purchased under these conditions are

called normal goods.† A decrease in incomes, however, results in a

decrease in demand.† In this situation,

consumers are more likely to buy inferior

goods, a term economists use to refer to products that people would

probably not buy if their incomes were higher.†

For example, if a consumer experiences a decline in income, he or she

may choose to buy a used car (classified as an inferior good) rather than a new

car (a normal good).

ō Consumer Taste:† Consumers

do not always want the same things.† For

this reason, changes in taste and preference also affect demand.† A different season, a new fashion trend, an

advertising campaign, new information and updated technology can influence

demand for a particular item or service.†

People will often stand in long lines for hours to be the first to buy

the latest smart phone or athletic shoe.†

When consumers want more of a product, they buy more of it at each and

every price available in the market.†

This shifts the entire demand curve to the right.† On the other hand, people may also grow tired

of a particular good and demand less of it at each price point.† This moves the entire demand curve to the

left.† Toys are a good example.† Certain ones may be very much in demand

during one Christmas season but totally out of fashion by the next one.†

Winter Weather Increases the Demand for Snowboards and

Decreases the Demand for Swimwear.

ō Changes in Population:† When the size of the population changes,

demand for most products changes, too.† More

people must be sheltered, clothed and fed when the population increases.† For example, American soldiers married and

started families in record numbers when they returned from World War II.† This resulted in a jump in the birthrate,

known as the baby boom, from 1945

through 1964.† Towns had to build new

schools to accommodate the growing number of children.† When these same children entered college,

universities had to build more dormitories and classrooms.† Today, the baby boomers are retirees, and the

market is adjusting to their demands for the services desired by senior

citizens.†

ō Changes in Expectation:† The way in which individuals envision the

future or anticipate the outcome of certain events is another determinant that

influences demand.† If consumers expect

that the price of a particular good or services is about to increase, demand

rises because buyers purchase more before the price goes up.† When consumers expect the price of a good or

service to decrease in the near future, demand temporarily decreases because

buyers delay their purchases until the price drops.† For example, letís say that you are in the

market for a new pair of running shoes.†

The salesperson suggests that you purchase them today because the store

plans to increase its prices next week.†

Because you expect a higher price in the future, you and other customers

increase the demand for the shoes today.†

If, on the other hand, the salesperson mentions that the same shoes are

going on sale next week, it is likely that you would postpone your

purchase.† Because you expect a lower

price in the future, you and your fellow buyers decrease the demand for the

shoes today.

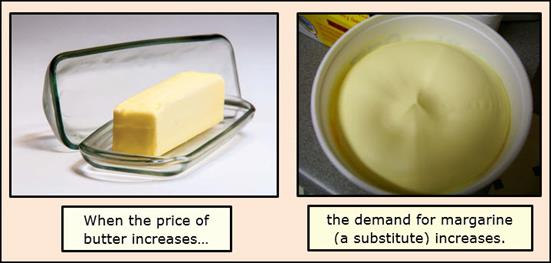

ō Changes in Related Products:† Changes in related goods or services also

impact demand.† Economists divide related

goods into two categories:† substitutes and complements.† Substitutes are

products that can be used to take the place of others.† The purchase of generic canned vegetables as

opposed to name-brand canned vegetables is one example.† For the most part, the demand for name-brand

canned goods increases when the price of the generic version, or substitute,

goes up.† For a minimal or no-price

difference, consumers frequently opt for the name brands and increase the

demand for them.† On the other hand, the

demand for the brand-name product decreases when the price of the generic, canned

vegetables decreases.† This occurs

because a significantly lower price often inspires shoppers to select generic

substitutes.† In this situation, name

brands experience a decrease in demand.†

Complements, such as computers and computer software, refer to products

that are purchased and used together.† If

computer prices decrease, consumers demand more computers and more

software.† If the price increases, buyers

demand fewer computers and, in turn, less software.

Go to Questions 14

through 22.

Go to Questions 14

through 22.

Whatís

next?

The

market system emphasizes the consumersí ability to buy what they want and can afford.† At the same time, it stresses that sellers

make enough profit to stay in business.†

In the next unit, you will learn about the supply side of the market.† How do economists define supply?† Is there a law of supply that counterbalances

the law of demand?† Are you a

supplier?† Before moving on to find the

answers to these and other questions concerning supply, review the names and

terms found in this unit; then, complete Questions 23 through 32.

Go to Questions 23

through 32.

Go to Questions 23

through 32.